By Kaleena Fraga

On this day in 1987, Ronald Reagan famously called on Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down this wall”–a wall which physically separated East and West Berlin, and symbolized the separation between the Soviet Block and the West.

On this day in 1987, Ronald Reagan famously called on Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down this wall”–a wall which physically separated East and West Berlin, and symbolized the separation between the Soviet Block and the West.

Yet the wall did not come down in 1987, or in 1988. It would not be torn down until 1989, after Reagan had left office, and after his vice president, George H.W. Bush, had been elected as president.

A few months before the wall fell, Bush had also advocated for its destruction, albeit in a less dramatic fashion than Reagan. During a speech in Mainz, Germany to celebrate the 40th anniversary of NATO, he noted that barriers in Austria and Hungary had recently been removed, and so:

“Let Berlin be next — let Berlin be next! Nowhere is the division between East and West seen more clearly than in Berlin. And there this brutal wall cuts neighbor from neighbor, brother from brother. And that wall stands as a monument to the failure of communism. It must come down.”

On November 9, 1989 Bush received word that the wall had been breeched.

To Bush, the fall of the wall represented a great symbolic victory, but also a danger of violence. He worried that police in East Germany would fire upon demonstrators, and that this could turn a cold war into a hot one. From the Soviets, the Bush White House received a plea for calm, urging the Americans to “not overreact.” Bush later recalled that, “[Gorbachev] worried about demonstrations in Germany that might get out of control, and he asked for understanding.”

To the gathered press, Bush gave a prepared statement which welcomed the fall of the wall, nothing that the “the tragic symbolism of the Berlin Wall…will have been overcome by the indomitable spirit of man’s desire for freedom.”

But Bush, noted biographer John Meacham in his book Destiny and Power: The American  Odyssey of George H.W. Bush, was more focused on what could go wrong rather than the symbolic triumph of the West over the Soviets, which led to a contentious exchange between the president and CBS reporter Lesley Stahl.

Odyssey of George H.W. Bush, was more focused on what could go wrong rather than the symbolic triumph of the West over the Soviets, which led to a contentious exchange between the president and CBS reporter Lesley Stahl.

“This is a great victory for our side in the big East-West battle, but you don’t seem elated,” said Stahl. “I’m wondering if you’re thinking of the problems.”

“I’m not an emotional kind of guy,” Bush replied.

“Well, how elated are you?”

“I’m very pleased.”

Democrats in Congress also sought a stronger response from the president. Senate Democratic leader George Mitchell thought Bush should fly to Berlin so that he could make a statement about the end of Communism, with the fallen wall as a dramatic background. House Majority Leader Dick Gephardt said that Bush was “inadequate to the moment.”

From the Soviets, Gorbachev warned of “unforeseen consequences.” Bush heard reports of violence in other Soviet republics. In the days and weeks that followed, it appeared that Soviet power in Bulgaria and Czechoslovakia were also faltering. In his diary, Bush wrote that Mitchell had been “nuts to suggest you pour gasoline on those embers.”

When Bush met with Gorbachev at the Malta Conference that December, he was cautiously optimistic, and prepared.

“I hope you have noticed,” he said to Gorbachev, “we have not responded with flamboyance or arrogance that would complicate Soviet relations…I have been called cautious or timid. I am cautious, but not timid. But I have conducted myself in ways not to complicate your life. That’s why I have not jumped up and down on the Berlin Wall.”

“Yes, we have seen that,” said Gorbachev, “and appreciate that.”

On December 3rd, the two men held the first ever joint press conference between an American president and a leader of the Soviet Union.

Expressing gratitude for Bush’s caution, and recognizing the danger of exaggeration, Gorbachev said that he and Bush agreed that “the characteristics of the cold war should be abandoned…the arms race, mistrust, psychological and ideological struggle, all those should be things of the past.”

Coming home, Bush found he faced criticism not only from the left, but also from the right–from within his own White House. Vice President Quayle, Bush wrote in his diary, saw a chance to become “the spokesman of the right,” a sort of disloyalty to Bush’s efforts that he had never been guilty of during his eight years as Reagan’s vice president.

Ultimately Bush’s caution about the fall of the wall allowed him to navigate fragile relationships with both Gorbachev and the Chancellor of Germany, Helmut Kohl. It allowed him to piece together a new, post-Cold War world order. His refusal to gloat despite pressure on both sides proved crucial, and can serve today as a lesson to other American leaders on the world stage.

does not eat in public.” A waitress later told UPI that the queen did not eat, but she did

does not eat in public.” A waitress later told UPI that the queen did not eat, but she did

Schoumatoff was standing at her easel painting the president when something in his demeanor changed. She later recalled: “He looked at me, his forehead furrowed in pain, and tried to smile. He put his left hand up to the back of his head and said, ‘I have a terrible pain in the back of my head.’ And then he collapsed.”

Schoumatoff was standing at her easel painting the president when something in his demeanor changed. She later recalled: “He looked at me, his forehead furrowed in pain, and tried to smile. He put his left hand up to the back of his head and said, ‘I have a terrible pain in the back of my head.’ And then he collapsed.” in his own right. Although his approval rating hovered in the

in his own right. Although his approval rating hovered in the

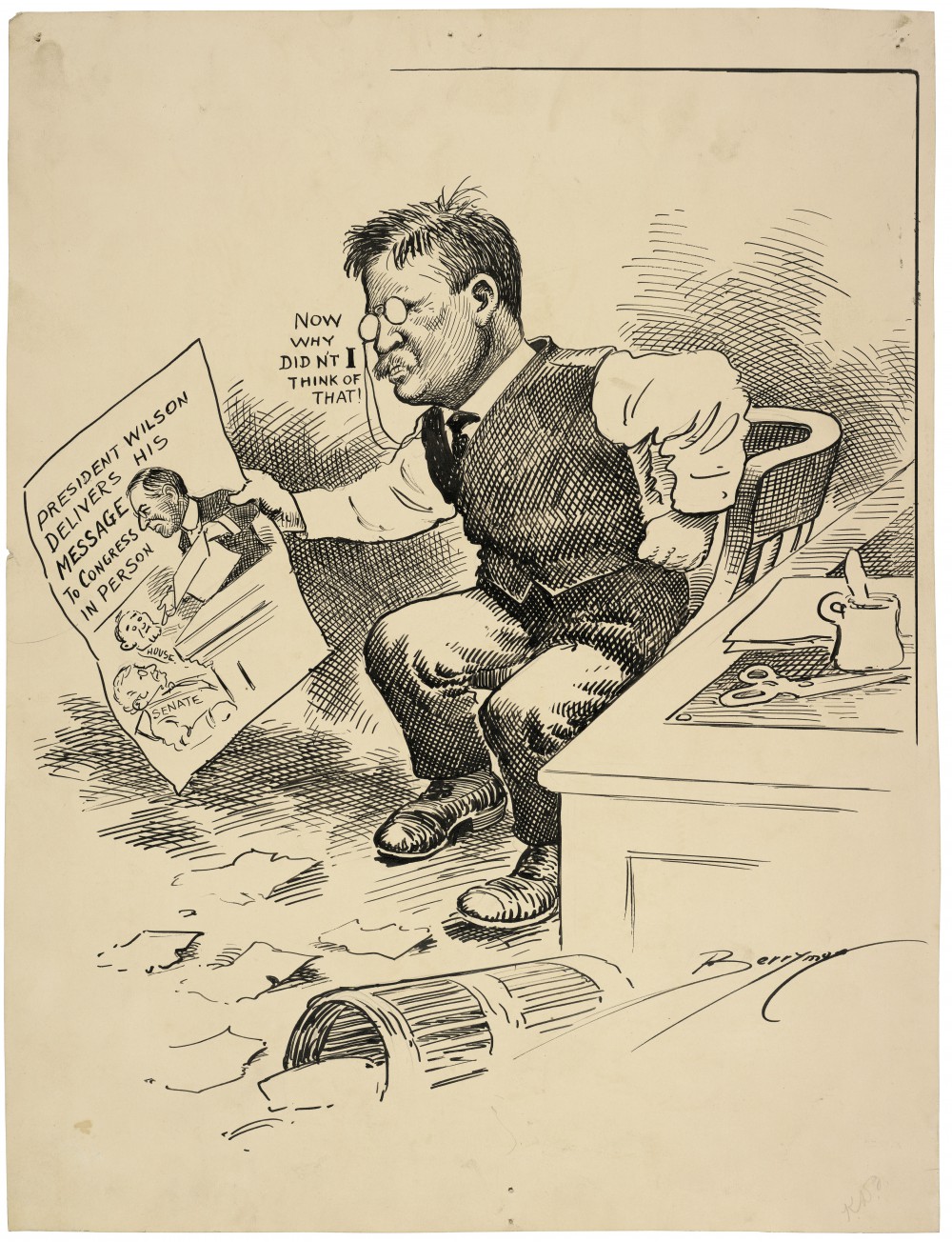

twenty-eight minutes. Each of his addresses to Congress were around or above the one hour mark. His speech was also the longest at 9,190 words (Washington’s, by comparison, was the shortest at 1,089 words).

twenty-eight minutes. Each of his addresses to Congress were around or above the one hour mark. His speech was also the longest at 9,190 words (Washington’s, by comparison, was the shortest at 1,089 words).