By Kaleena Fraga

(To check out this piece in podcast form, click here)

Amid a contentious government shutdown, Speaker Nancy Pelosi has written President Trump a letter, suggesting that in lieu of delivering a State of the Union speech, as the president intends, he submit his address in writing.

Although Americans today are accustomed to seeing the president deliver the SOTU, Pelosi notes in her letter that “during the 19th century and up until the presidency of Woodrow Wilson, these annual State of the Union messages were delivered to Congress in writing.” Pelosi also notes that a SOTU has never been delivered amidst a government shutdown.

“I suggest,” Pelosi writes, “that we work together to determine another suitable date after the government has re-opened for this address or for you to consider delivering your State of the Union address in writing to Congress on January 29th.”

Although the State of the Union started as an oral address–both George Washington and John Adams delivered speeches to Congress–Thomas Jefferson was the first to balk at the tradition.

Jefferson had several reasons why he believed a written address was superior to a speech. First of all, the third president nursed a fear of public speaking. He also believed that a letter was more efficient than a speech–that it would take less time to read than to listen, and that a written document would give legislators time to think about their response. Historians have also noted that giving a speech had a king-like aura, something that a republican like Jefferson would abhor.

Then again, Jefferson could have simply found trudging to Congress to give a speech inconvenient.

In any case, the tradition that Jefferson set remained for over one hundred years, until Woodrow Wilson decide to return to the ways of Washington and Adams, and give a speech before Congress instead of simply sending a letter.

At the time this was considered far outside the norm. The Washington Post reported that “Washington is amazed” and that “disbelief” was expressed in Congress when members heard the president intended to give a speech. At the time, the paper seemed confident that such displays would not “become habit.”

Since then, a spoken SOTU has indeed become a national habit, even more so than in Wilson’s day thanks to mass communication tools like radio, television, and internet.

That’s not to say that the written version of the SOTU has been abandoned entirely–as lame duck presidents, Truman, Eisenhower, and Carter chose to submit a written message instead of giving a speech before Congress.

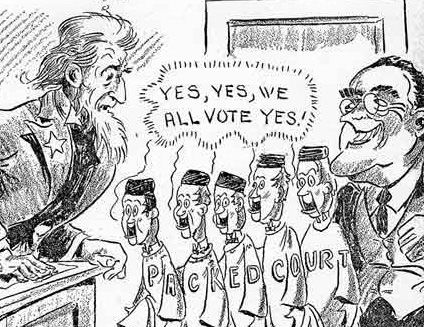

Whether or not Trump will heed Pelosi’s advice has yet to be seen, and certainly a president might balk at giving up the bully pulpit power of television. In any case, we’ll leave you with a cartoon of Theodore Roosevelt, who was thoroughly dismayed that Wilson had the idea of a SOTU speech, something that Roosevelt himself would have enthusiastically embraced.

Addressing a

Addressing a

On October 3rd, 1921, Taft finally realized his ultimate goal and was appointed as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court by President Warren Harding. “This is,” Taft declared, “the greatest day of my life.”

On October 3rd, 1921, Taft finally realized his ultimate goal and was appointed as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court by President Warren Harding. “This is,” Taft declared, “the greatest day of my life.” beautify the city, and ordered 2,000 cherry trees from Japan as part of this effort. Taft too forever changed the landscape of the capitol. He lobbied Congress to put aside funds for a new Supreme Court building–the one we know today–moving the justices out of the old Senate Chamber and into a building of their own. Taft

beautify the city, and ordered 2,000 cherry trees from Japan as part of this effort. Taft too forever changed the landscape of the capitol. He lobbied Congress to put aside funds for a new Supreme Court building–the one we know today–moving the justices out of the old Senate Chamber and into a building of their own. Taft