How campaign rivals become running mates

By Kaleena Fraga

Check out this post in podcast form! Listen HERE.

Who will Joe Biden pick as his running mate? The former vice president reportedly has a shortlist of names to fill his previous White House role. Some, like Kamala Harris and Elizabeth Warren, battled Biden for the nomination.

Harris, in particular, launched a grenade at Biden during an early debate. The California senator levied charges of racism against Biden, because of his opposition to busing in the 1970s. Today, Biden insiders bristle at her “lack of remorse” over the incident.

Should Harris’ attack be held against her? If chosen to be Biden’s VP pick, she would in fact join a long tradition of campaign rivals who became running mates.

John Adams and Thomas Jefferson

Arguably, this tradition has roots in the very beginning of the Republic—although candidates then had no say over their vice president. The runner-up automatically became VP, which is how Thomas Jefferson came to serve his frenemy John Adams in 1796.

The two men were a study in contrasts. Adams, the rotund, loquacious Northerner represented the Federalists; Jefferson, the statuesque, quiet Southerner stood for the Democratic-Republicans.

As friends, the two men had accomplished great things. Both had served in the Continental Congress and had worked together to create the Declaration of Independence. But their relationship had soured. When Jefferson became Adams’ vice president most agreed that perhaps it didn’t make sense to make the runner up in the election the vice president—especially if he represented the opposing party.

In 1800, they would run against each other again. This time, they would pick “running mates” to join them in battle. (This caused significant confusion —while the Federalists carefully divided their votes between Adams and his running mate, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, the Democratic-Republicans voted enthusiastically for both Jefferson and Aaron Burr, causing a tie.)

The 12th amendment, ratified in 1804, would forever change how elections work. It created a system where electors would cast one vote for president, and one vote for vice president.

However, it wouldn’t mean the end of rivals becoming running mates.

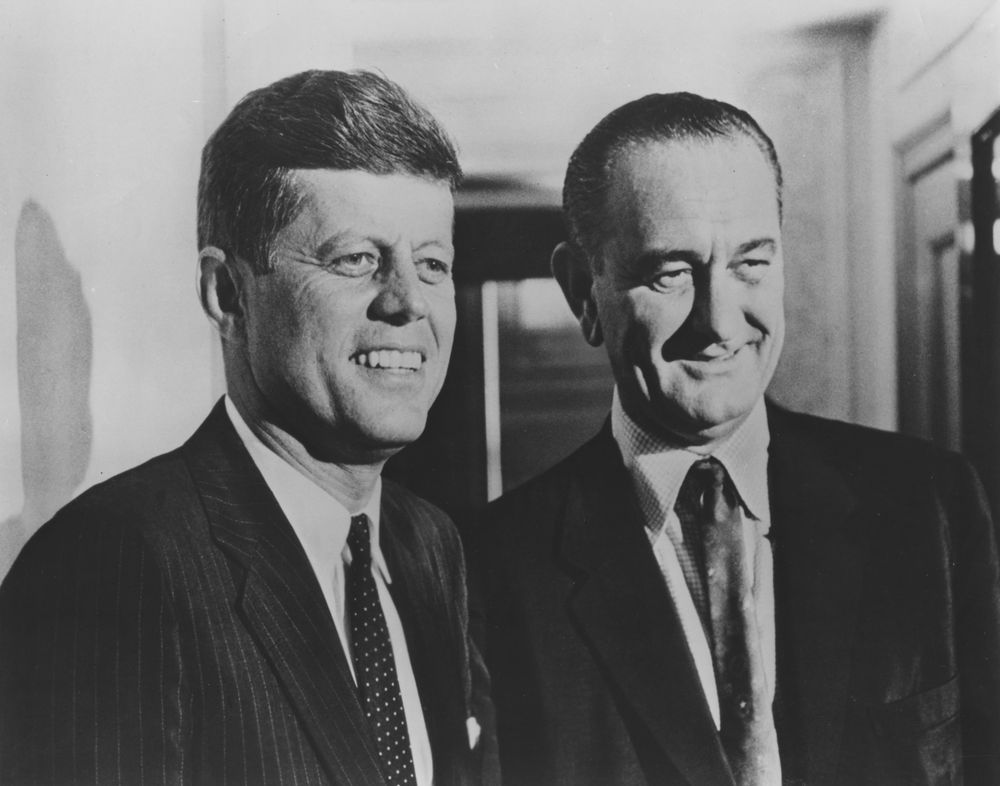

John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson

Once Lyndon B. Johnson was picked to be John F. Kennedy’s vice president, he had his staff look up the odds of a V.P becoming president. They weren’t bad.

“I looked it up: one out of every four Presidents has died in office. I’m a gamblin’ man, darlin’, and this is the only chance I got.”

Johnson to journalist Clare Booth Luce

Kennedy and Johnson had first worked together in Congress. Johnson, the Texan Senate Majority leader, thought little of the young senator from Massachusetts. Johnson called Kennedy “pathetic” and “not a man’s man.”

When both men threw their hats in the ring to become president, the attacks escalated. Johnson seized upon the issue of the day—that Kennedy, if elected, would be the nation’s first Catholic president. He also called his opponent, who suffered from various health issues, a “little scrawny fellow with rickets.”

Despite this, Kennedy saw the appeal of having Johnson on his ticket. He knew he needed the South and Johnson—from Texas—could deliver crucial votes. Not everyone in the Kennedy camp agreed. Bobby Kennedy, the future president’s brother, openly despised Johnson—and Johnson despised Bobby.

This animosity only deepened when Bobby tried to get Johnson to withdraw from the ticket. Bobby tried three times. Three times, Johnson refused. LBJ, who had hated Bobby since knowing him as a Congressional staffer, called the future president’s brother, “a grandstanding little runt.”

On election night, Texas did prove crucial to Kennedy’s victory. And LBJ made sure that Jack Kennedy knew it. “I see you are losing Ohio,” he told Kennedy during an election night phone call. “I’m carrying Texas.”

Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush

During the 1980 election, George H.W. Bush competed against Ronald Reagan in 33 primaries, losing 29 of them. At times, the race to the nomination became openly acrimonious.

Bush feared that Reagan was too conservative. So, he remained in the race, even as he lost primary after primary. Bush stuck to his moderate guns. He famously labeled Reagan’s economic plan as “voodoo economics.”

Reagan, for his part, believed that Bush “lacked spunk” and bowed too easily to political pressure. This opinion was partially formed in New Hampshire. Bush agreed to a 1:1 debate in New Hampshire, but Reagan then turned around and invited all the other candidates. (From the confusion came Reagan’s famous line: “I paid for this microphone!”) Reagan wasn’t impressed by how Bush just sat there. He believed it showed a “lack of courage.”

Once he secured the nomination, Reagan did not especially want to pick Bush as his running mate. He postured to bring the former president Gerald Ford to the ticket, but Ford’s ambivalence toward the idea, and the whispers of a “co-presidency” turned this plan into dust.

Running out of time, Reagan turned to Bush. Bush, sitting in his hotel room at the Republican convention and watching the wild speculation over the Ford rumors, believed that Reagan had called to let him know that he’d picked the former president. Instead, Reagan offered Bush the vice presidency.

Despite becoming running mates, the two men lacked chemistry. A few weeks into Reagan’s first term, Bush even sighed that, despite his efforts he, “couldn’t understand Reagan.”

—

Who will Joe Biden pick as his running mate? Biden has said he will make an announcement in August.

Biden insiders may dislike Kamala Harris for her attacks on their candidate. They may dislike her for her “lack of remorse” and her “ambition” to be president. But if Harris is chosen as Joe Biden’s running mate, she would join a long line of men who struck an alliance with former campaign rivals.

—

We’re kind of obsessed with the vice presidency. Next, read about LBJ and the Odds of Becoming President, The Path from the Vice Presidency to the Presidency, and about the 25th Amendment.

Addressing a

Addressing a

come to formally greet him–in fact, he was

come to formally greet him–in fact, he was