By Kaleena Fraga

Even before the newest Supreme Court justice, Brett Kavanaugh, placed his hand on the Bible and swore to uphold the Constitution, Democrats in Congress faced pressure to remove him from the bench. A petition to impeach the judge quickly hit over 150,000 signatures and think pieces arguing for and against impeachment began to pop up across the Internet.

Faced with this, Democrats in Congress hesitated. “I have enough people on my back to impeach the president!” House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi exclaimed, when asked if she would impeach Kavanaugh.

Hesitancy on their part is understandable: attempts to impeach justices from the Supreme Court have been few and far between, and have never resulted in an actual impeachment.

The first example of this came early in American history. Thomas Jefferson had swept to power in the “revolution of 1800”, a repudiation of the last twelve years of Federalist rule. Still, despite the ascension of Jefferson’s party to both houses of Congress, most of the Supreme Court remained staunchly Federalist.

One of Jefferson’s first moves as president was to repeal the Judiciary Act of 1801–an act with a dry title and a dramatic history. Jefferson’s predecessor, his frenemy John Adams, had passed the Act in the waning weeks of his one-term in office. It reduced the size of the Supreme Court, and, more importantly, created a lower level of courts which Adams briskly filled with like-minded Federalists with life-terms. Jefferson and his allies accused Adams of packing the court with so-called “Midnight Judges“, giving birth to the lore that the ink on Adams’ appointments had not dried by the time Adams left Washington, skipping out on Jefferson’s inauguration.

When the Judiciary Act of 1801 was repealed (and replaced with the Judiciary Act of 1802, eliminating the circuit judgeships that Adams had created), Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase–a Federalist with a “volcanic” personality–declared in front of a Baltimore jury that “Our republican Constitution will sink into a mobocracy–the worst of all possible governments.”

Jefferson already disliked the justices of the Supreme Court (his biographer Jon Meacham writes that Jefferson’s “hatred of his cousin John Marshall [the Chief Justice] was cordial, but it was hatred nonetheless”) and found that this outburst from Chase could not stand. He wrote to Congressman Joseph H. Nicholson asking: “Ought this seditious and official attack on the principles of our Constitution and on the proceedings of a State go unpunished; and to whom so pointedly as yourself will the public look for the necessary measures?”

Ever the behind-the-scenes man, Jefferson professed that it would be better “that I should not interfere.”

Jefferson’s cousin and friend, Congressman John Randolph, launched impeachment proceedings against Justice Chase. Chase argued he was being persecuted for his political convictions rather than any actual crimes. (Indeed, one of the articles of impeachment pointed to Chase’s political speech from the bench).

Chase escaped with an acquittal. His impeachment trial set two norms: that judges should not be removed based on their political beliefs, and that judges should remain non-partisan while speaking from the bench.

One hundred and sixty-five years later, a second Supreme Court justice, Abe Fortas, faced impeachment proceedings. Rather than face a trial, he resigned.

Between the dawn of the Republic and 2010, fourteen other federal judges (serving on lower courts) have faced charges of impeachment–eight were removed from office, three were acquitted, and three resigned. It’s no wonder that Democrats today hesitate to engage in impeachment rhetoric when it comes to Kavanaugh; given the history, it would be an extreme move on their part.

Still, for those who shudder at the partisanship plaguing the nation and the Supreme Court today, recall that amidst Jefferson’s time as president, he infuriated the Federalists by such actions as repealing the Judiciary Act of 1801 and attempting to impeach Samuel Chase. One frustrated American wrote to the president he hoped “that your Excellency might be beheaded within one year.”

Addressing a

Addressing a

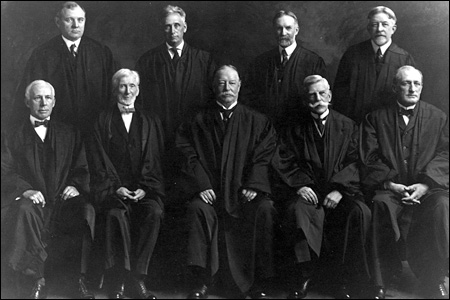

On October 3rd, 1921, Taft finally realized his ultimate goal and was appointed as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court by President Warren Harding. “This is,” Taft declared, “the greatest day of my life.”

On October 3rd, 1921, Taft finally realized his ultimate goal and was appointed as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court by President Warren Harding. “This is,” Taft declared, “the greatest day of my life.” beautify the city, and ordered 2,000 cherry trees from Japan as part of this effort. Taft too forever changed the landscape of the capitol. He lobbied Congress to put aside funds for a new Supreme Court building–the one we know today–moving the justices out of the old Senate Chamber and into a building of their own. Taft

beautify the city, and ordered 2,000 cherry trees from Japan as part of this effort. Taft too forever changed the landscape of the capitol. He lobbied Congress to put aside funds for a new Supreme Court building–the one we know today–moving the justices out of the old Senate Chamber and into a building of their own. Taft