By Kaleena Fraga

During the 1770s, Americans had more to contend with than the Revolutionary War. Aside from the British, the country was also battling a smallpox epidemic, which tore through the Thirteen Colonies from 1775 to 1782.

To George Washington, the disease was as dangerous — if not more — than the British. By some estimates, more troops died of smallpox than they did in battle.

Washington knew he needed to act. But the only weapon he had at his disposal was a process called variolation. It protected against smallpox, but it was so controversial in the Colonies that some places had banned it.

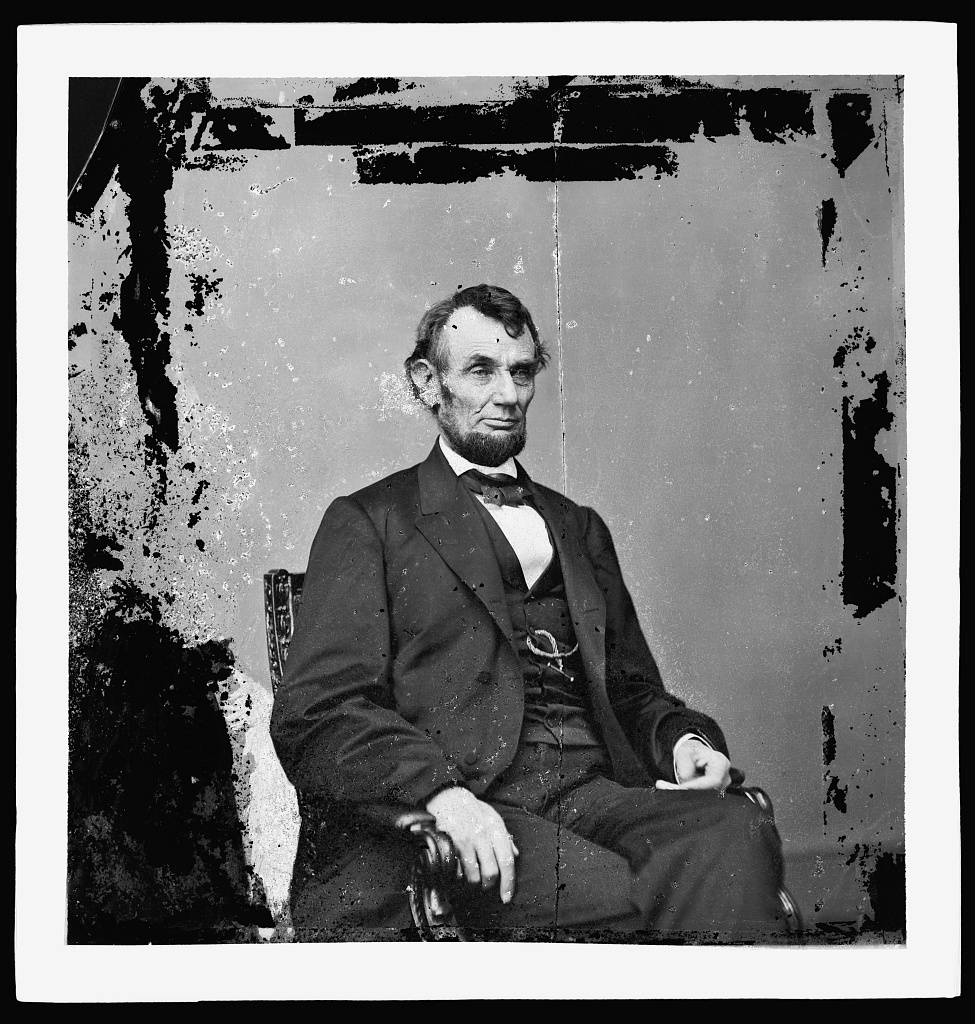

George Washington’s Experience With Smallpox

By the time the Revolutionary War broke out in 1775, very few Americans had ever had smallpox. The disease was endemic in Europe but the isolation of American towns and farms had limited its spread in the Colonies.

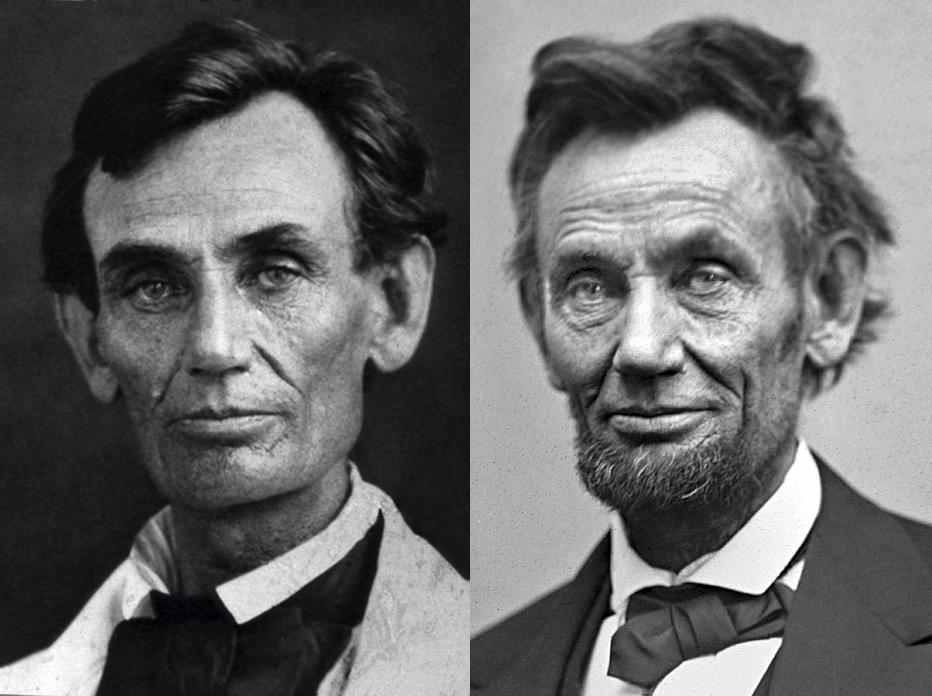

George Washington, however, was one of the few Americans who contracted the disease. He’d fallen ill with smallpox during a visit to Barbados with his brother, Lawrence, who’d hoped that the warm air would help his tuberculosis.

They stayed with a merchant named Gedney Clarke. However, Washington was reluctant to do so.

“We went,—myself with some reluctance, as the smallpox was in his family,” he wrote. Indeed, just two weeks later, Washington had smallpox. “Was strongly attacked with the small Pox,” he noted grimly in his journal — the last entry he made for 24 days.

Smallpox, caused by the Variola major virus, can spread through the air, through bodily fluids, or even by touching contaminated clothing. People with the disease experience fever, headaches, body pains, and eventually a bad rash. Some — about one in every two victims in the 18th-century — die after two weeks or so. Those who survive can take up to a month to recover.

Washington was lucky. After contracting the disease, he only had some scarring on his nose — as well as a lifelong immunity.

During the Revolutionary War, Washington’s immunity might have saved his life. It certainly gave him an inside perspective on what the disease could do.

Smallpox And The Revolutionary War

When the British arrived to quash the American rebellion, they carried more than guns and bayonets. They also brought smallpox.

George Washington was well-aware of the danger. Soon after he took command of the army in the summer of 1775, Washington wrote to the president of the Continental Congress that he was “particularly attentive to the least Symptoms of the Smallpox.” Vowing to quarantine anyone who seemed to have the disease, Washington added that he would “continue the utmost Vigilance against this most dangerous enemy.”

During the Siege of Boston, which followed the Battle of Lexington and Concord, Washington was put to the test. As Bostonians tried to seek refuge with the army, Washington was forced to turn them away.

“Every precaution must be used to prevent its spreading,” Washington told one of his subordinates.

Still, Washington was hesitant to inoculate his troops. He worried that doing so would put them out of commission for weeks, just when he needed a strong hand against the British. Initially, he banned inoculation.

“The Enemy, knowing it, will certainly take Advantage of our Situation,” he wrote. Instead, he ordered the inoculation of new troops, figuring that they could take time to recover.

But the disease continued to ravage the American army. When General John Thomas marched on Quebec, he shrugged off Washington’s strict anti-smallpox procedures, and subsequently lost between one-third and one-half of his 10,000 troops to the disease.

“The smallpox is ten times more terrible than Britons, Canadians, and Indians together,” John Adams despaired in 1776.

Washington knew he had to act. But he would have to fight more than smallpox itself — he’d also have to fight public opinion.

George Washington And Variolation

George Washington knew what to do when it came to fighting the British. And he knew what was needed to contain smallpox from spreading throughout the Colonies and his army.

Inoculation against smallpox dated back to ancient China. But in Colonial America, the process, called variolation, was controversial and dangerous.

It involved cutting an incision in someone’s skin and inserting a small amount of the live smallpox virus. (In 1796, Edward Jenner would invent a way to do this using cowpox.)

But the procedure still had a fatality rate of 5-10% — not great. King George III’s son died an agonizing death when his dose was improperly applied.

And many Americans didn’t trust the process. When inoculation was tried out in Boston in 1721, anti-vaxxers of the 18th-century were outraged and firebombed the house of the man behind the immunization effort. They believed he was actually spreading the disease — and defying the will of God.

Even in Washington’s time, variolation was illegal in his home state of Virginia.

But the general knew he needed to act. Washington was worried that the British would figure out the chink in the Americans’ armor, and use their men as walking bioweapons.

After some initial hesitation, Washington made his choice. He would inoculate his army. On February 5, 1777, he wrote a letter to John Hancock, the president of the Second Continental Congress, informing him of his decision.

“The small pox has made such Head in every Quarter that I find it impossible to keep it from spreading thro’ the whole Army in the natural way,” Washington stated.

“I have therefore determined, not only to innoculate all the Troops now here, that have not had it, but shall order Docr. Shippen to innoculate the Recruits as fast as they come in to Philadelphia.”

The Impact Of Washington’s Actions

Although George Washington wavered before making his decision, his orders to inoculate the army may have helped the Americans win the war.

By the end of 1777, some 40,000 soldiers had been given protection against the virus. Infection rates dropped from 20% to 1%. And even holdouts in the Continental Congress were convinced by Washington’s success — they repealed existing bans on variolation across the Colonies.

All of this had to be done in secret. “I need not mention the necessity of as much secrecy as the nature of the Subject will admit of,” Washington wrote, “it being beyond doubt, that the Enemy will avail themselves of the event as far as they can.”

Stealthily, the Americans armed themselves against smallpox. And they prepared to meet the British on the battlefield in full strength.

Not everyone was protected, however. Some slaves had defected to the British, hoping for freedom. They were not inoculated by the British — who were already largely protected — and suffered from smallpox in large numbers. Similarly, Native Americans had no such protection, and also struggled to survive the surge of the disease.

But Washington’s actions add a significant angle to his legacy. When it came to defeating an invisible foe, he used the only weapon he had available to him — risks and all.