By Kaleena Fraga

Former FBI director James Comey made waves recently when he suggested that Joe Biden may want to think about pardoning Donald Trump

Asked about the likelihood of a Trump pardon, Comey said that it could be a “part of healing the country.” He acknowledged that Trump might take it as “an admission of guilt” and refuse to accept.

When Gerald Ford assumed the presidency following Richard Nixon’s resignation in 1974, he faced a similar decision. Ultimately, Ford decided to pardon Nixon—to the outrage of many. The Ford pardon was so unpopular that it may have even cost him reelection.

So, how did Ford reach his decision? And how do Americans regard Ford’s pardon of Nixon today?

Why Did Ford Pardon Nixon?

American political history is full of odd honors—shortest presidency (William Henry Harrison); most impeachments (Donald Trump); etc—and Ford’s claim to fame is that he is the only unelected president. He was plucked from Congress when Richard Nixon’s vice president, Spiro Agnew, resigned, and became president when Nixon followed suit in August 1974.

Ford’s first week in office was bizarre. For the first 10 days of his presidency, he commuted from his family’s house in Alexandria, Virginia. All the while, he was weighing what to do about his predecessor.

Ford had been considering the possibility of a Nixon pardon since before he became president. Al Haig, Nixon’s chief of staff, had approached Ford 10 days before Nixon’s resignation and proposed a deal—the presidency, in exchange for a pardon. That is, Nixon would step down if Ford promised a pardon. Ford said no.

Speaking later to Bob Woodward—who uncovered the Watergate scandal and writes prolifically about presidencies—Ford said, “It was a deal, but it never became a deal because I never accepted.”

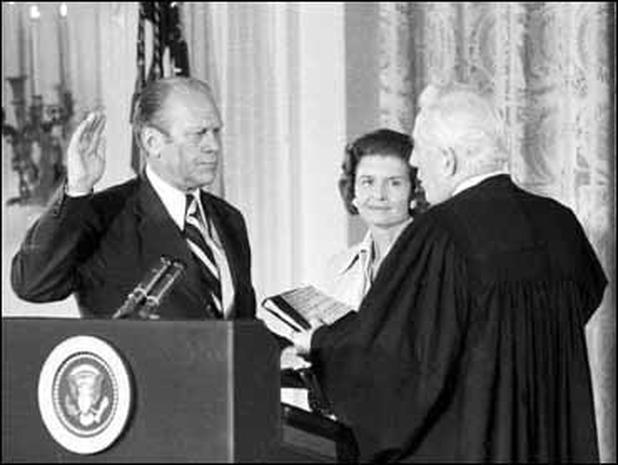

When Ford was hastily sworn in following Nixon’s resignation, he called for unity. My fellow Americans,” Ford famously said, “our long national nightmare is over.”

He went on to say: “As we bind up the internal wounds of Watergate, more painful and more poisonous than those of foreign wars, let us restore the golden rule to our political process, and let brotherly love purge our hearts of suspicion and of hate.”

But Watergate’s wounds were still fresh. Conflict raged over Nixon’s tapes and files, which the ex-president claimed as executive privilege; the House Judiciary Committee released their damning report on Nixon’s conduct; and Nixon’s lawyer claimed that his client could not receive a fair trial in the United States.

The White House counsel and a friend of Nixon, Leonard Garment, even feared that the former president might kill himself. On August 28th, he wrote Ford a memo which warned that: “The national mood of conciliation will diminish…the whole miserable tragedy will be played out to God knows what ugly and wounding conclusion.”

Garment urged Ford to pardon Nixon—and soon.

Ford had yet to make any decision. But an afternoon press conference pushed him toward issuing a pardon. He spent most of the session with the press deflecting questions about Nixon. Afterwards, Ford recalled thinking: “Every press conference from now on, regardless of the ground rules, will degenerate into a Q&A on, ‘Am I going to pardon Mr. Nixon?'”

Tw days later, Ford gathered a group of advisors in the Oval Office. “I’m very much inclined,” he told them, “to grant Nixon immunity from further prosecution.”

His reasons were varied. Ford thought it would be a “degrading spectacle” for a former president to go to prison and that the press would continue to drag out “the whole rotten mess” of Watergate.

His advisors largely agreed, but argued against pardoning Nixon so soon after Ford had assumed office.

Ford asked, “Will there ever be a right time?”

Ford Pardons Nixon

On September 8th, 1974—roughly one month into his presidency—Gerald Ford pardoned Richard Nixon.

“[Watergate] is an American tragedy in which we all have played a part,” Ford said. “It could go on and on and on, or someone must write the end to it. I have concluded that only I can do that, and if I can, I must.”

Ford went on: “My conscience tells me clearly and certainly that I cannot prolong the bad dreams that continue to reopen a chapter that is closed. My conscience tells me that only I, as President, have the constitutional power to firmly shut and seal this book. My conscience tells me it is my duty, not merely to proclaim domestic tranquillity but to use every means that I have to insure it.”

He finished by saying, “Finally, I feel that Richard Nixon and his loved ones have suffered enough and will continue to suffer, no matter what I do, no matter what we, as a great and good nation, can do together to make his goal of peace come true.”

Ford then read a proclamation, and signed it, granting Nixon a presidential pardon.

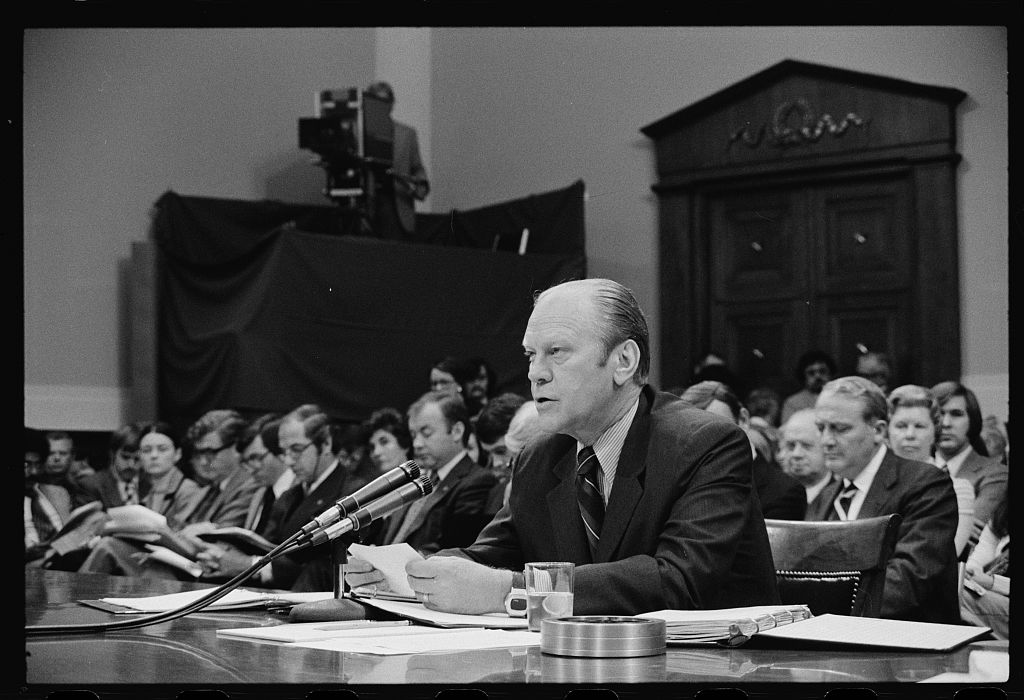

A month later, Ford explained to Congress that his primary motivation in issuing the pardon was to help the nation close the door on Watergate.

“I was absolutely convinced…that if we had had [an] indictment, a trial, a conviction, and anything else that transpired after this that the attention of the President, the Congress and the American people would have been diverted from the problems that we have to solve. And that was the principle reason for my granting of the pardon,” Ford said. He spoke with confidence, but later acknowledged that the pardon had been his most difficult domestic decision.

Ford had another, less understood, reason to pardon Nixon. Benton Becker, who served as Ford’s lawyer at the time, explained in a 2014 panel that Nixon’s acceptance of Ford’s pardon acted as an admission of guilt. He cited Burdick vs. United States, a 1915 Supreme Court ruling in which the court decided that a pardon carried an “imputation of guilt”. Therefore, accepting a pardon was an “admission of guilt.”

Becker—who had the unenviable task of explaining this to Nixon—recalled that Nixon—after some convincing—agreed to the Court’s interpretation. Ford carried a part of the Burdick decision in his pocket after he left the White House, in case anyone asked him to explain the pardon.

How Did The Country React To Ford’s Pardon Of Nixon?

The immediate reaction to Ford’s announcement was outrage. Carl Bernstein, Bob Woodward’s investigative partner, called Woodward and snarled: “The son of a bitch pardoned the son of a bitch.”

Ford paid an immediate price for his actions. According to a series of Gallup polls, Ford’s approval rating dropped from 66% in early September to 50% later that month; by January 1975, he’d sunk to a 37% approval rating. In the months leading up to the 1976 election—which Ford would lose to Jimmy Carter, after fighting off Ronald Reagan during the Republican primaries—Gallup reported that 55% of Americans thought that Ford had done the wrong thing in pardoning Nixon.

But over time, opinions about Ford’s pardon of Nixon changed. Bernstein acknowledged in 2014 that Ford’s pardon had taken “great courage.” Woodward likewise called the pardon “an act of courage.” In 2001, Senator Ted Kennedy awarded Ford the “Profile in Courage” award at the John F. Kennedy Library. Kennedy recalled that he had come out against the pardon in 1974. “But time has a way of clarifying past events, and now we see that President Ford was right,” Kennedy said. “His courage and dedication to our country made it possible for us to begin the process of healing and put the tragedy of Watergate behind us.”

In 2006, Richard Ben-Veniste, a former Watergate prosecutor and a Democrat wrote: “Did Ford make the right decision in pardoning his predecessor? The answer to that question is more nuanced than either the howls of outrage that greeted the pardon three decades ago or the general acceptance with which it is viewed now.”

That is—like most things in history—the ultimate legacy of Ford’s decision is complex.

—

Ford pardoned Nixon and paid the political price. Will Biden pardon Trump? Should he?

Some outlets, echoing Ford’s argument of national unity, say yes. The Baltimore Sun called the possibility of a pardon “tension calming.” The Independent went even further, calling a Biden-Trump pardon: “the only path forward.”

History does not repeat; but it does rhyme—and Trump and Nixon are not the same president. In a piece in the Dispatch, Professor Mary Stuckey of Penn State notes that: “There was no violence associated with Richard Nixon or Watergate.” The stakes, in other words, are different. Professor Sean Wilentz of Princeton also notes that Ford pardoned Nixon for his role in the Watergate scandal alone; a pardon of Trump would “[halt] further investigation and possible prosecution concerning the serious violation of several important federal laws arising from several distinct episodes dating back to the 2016 campaign.”

Biden may be eager to clear Trump from the American headspace, but Trump won’t be going anywhere for awhile—on January 19th, his impeachment trial is set to begin in the Senate.

That all but ensures that the first several days of Biden’s term will be cluttered with Trump news.

Ford and his family would not move to the White House until 10 days into his term, and in the meantime Ford would continue to commute from his home in Alexandria, Virginia. The

Ford and his family would not move to the White House until 10 days into his term, and in the meantime Ford would continue to commute from his home in Alexandria, Virginia. The  words…my fellow Americans, we have a lot of work to do.” To Congress he said, “I do not want a honeymoon with you. I want a good marriage.” Ford, who had climbed the ropes in Washington as a member of Congress, seemed uniquely able to build such a relationship. Yet he would veto 66 bills passed by the Democratic Congress, many of which were then overridden by Congress–the largest percentage of overrides since Congress overrode Andrew Johnson’s vetoes following his unexpected ascension to the presidency.

words…my fellow Americans, we have a lot of work to do.” To Congress he said, “I do not want a honeymoon with you. I want a good marriage.” Ford, who had climbed the ropes in Washington as a member of Congress, seemed uniquely able to build such a relationship. Yet he would veto 66 bills passed by the Democratic Congress, many of which were then overridden by Congress–the largest percentage of overrides since Congress overrode Andrew Johnson’s vetoes following his unexpected ascension to the presidency.