By Kaleena Fraga

John Tyler is best known for two things. One, he was the “Tyler” in “Tippecanoe and Tyler too.” Second, he was the first vice president to become president, after William Henry Harrison died just one month into his presidency.

But Tyler’s legacy contains another facet as well. After his presidency, he became an enthusiastic supporter of the Confederacy.

John Tyler’s Path to the Presidency

John Tyler was born on March 29, 1790, to a slave-holding family in Virginia. He was raised to be a member of the Southern gentry, receiving a top-notch education as his family’s dozens of slaves toiled on the plantation outside.

As a young man, Tyler used his connections among Southern elite to secure a place in the Virginia House of Delegates — which led to a seat on the U.S. House of Representatives, a stint as governor of Virginia, and a seat in the U.S. Senate.

In politics, Tyler made his views known. He distrusted federal overreach — and voted to censure legislators who supported the Bank of the United States. He did not support the Missouri Compromise of 1820 — Tyler believed slavery should be legal everywhere. And he deeply disliked the populist Democrat Andrew Jackson, to such an extent that Tyler left the Democratic party and joined the new anti-Jackson Whig party.

The Whigs maneuvered to block Jackson’s power. They failed in stopping his vice president, Martin Van Buren, from succeeding Jackson in 1836. But in 1840, their ticket of William Henry Harrison (the hero of the Battle of Tippecanoe) and Tyler led to victory — and to History First’s favorite song:

But Harrison died just one month into his presidency.

This was a first. No president had died in office before. And no one was exactly sure what to do. Yes, Tyler would take power — but was he the “president”? Some called him “His Accidency.” But Tyler set a precedent for vice presidents becoming president and not just an acting president.

As the president — and in a sign of things to come — Tyler bucked his party in favor of state’s rights. His veto of bills attempting to establish a national bank infuriated his fellow Whigs, who responded by launching impeachment proceedings against him. (The first time this had been done.)

Tyler survived. However, the furious Whigs expelled him from their party.

“Popularity, I have always thought, may aptly be compared to a coquette,” Tyler mused. “The more you woo her, the more apt is she to elude your embrace.”

In 1844, Tyler, lacking a party, was forced to run as a third-party candidate. He eventually threw his weight behind the Democrat, James K. Polk, to deny the Whigs a victory.

The Emergence Of The Confederacy

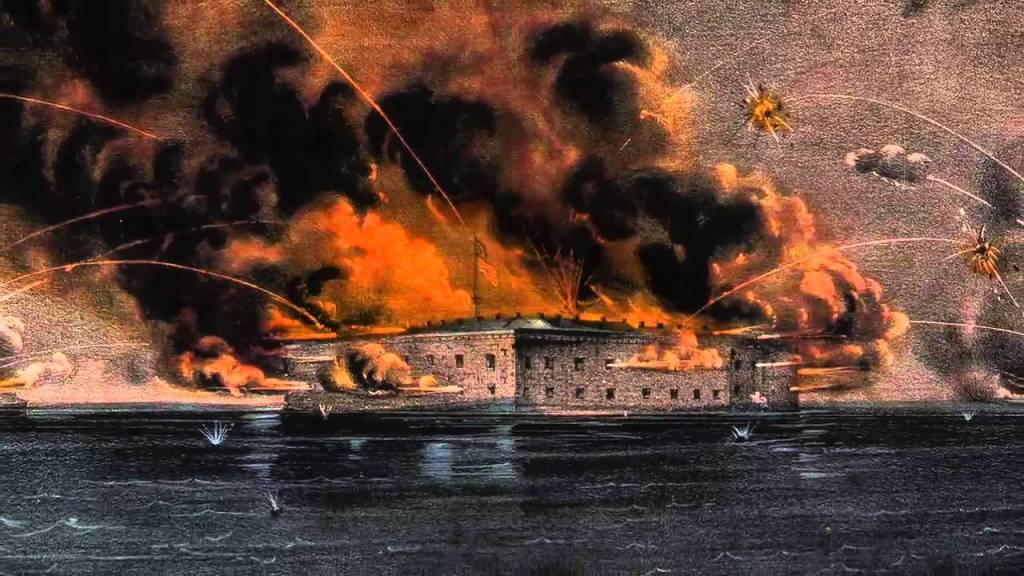

After Polk succeeded Tyler, the 10th president returned home to Virginia. But storm clouds were on the horizon. In just fifteen years, the country would shatter into the bloody conflict of the Civil War.

Tyler watched the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 with deep displeasure. “The day of doom for the great model republic is at hand,” he wrote. Southerners agreed with Tyler. Before long, rumbles of secession filled the country.

However, Tyler, to his credit, initially tried to prevent violence. He convened a “Peace Convention” after six states had seceded from the Union, with the goal of finding alternatives to disunion. Delegates from all states were invited to attend the Convention, which took place in February 1861.

But Tyler’s efforts were in vain. He had slowed — but could not stop — the outbreak of bloodshed.

Instead, he decided to give up on the cause of peace. Tyler threw his weight behind the nascent Confederacy. He voted for Virginia to secede and was soon elected to join the Confederate House of Representatives. His granddaughter was even the first person to raise the Confederate flag.

“When he takes this action, he knows he’s a rebel,” noted Edward P. Crapol, who wrote a biography of Tyler called John Tyler, The Accidental President. “He knows what he’s done. They’re not playing bean bag, if you know what I mean. This is very serious stuff.”

However, Tyler died before he could serve the Confederacy. On January 12, 1862, he died of a likely stroke at the Ballard Hotel in Richmond, Virginia.

John Tyler’s Legacy Today

After John Tyler died, the Confederacy celebrated him as one of their founding heroes. His coffin was draped with a Confederate flag. The Confederate president, Jefferson Davis, arranged a parade in his honor and ordered flags lowered to half-mast.

But in the North, news of John Tyler’s death was greeted with stony silence. He was seen as a traitor. Abraham Lincoln issued no word about his passing — marking the first, and only, time in American history that an official proclamation wasn’t issued following a president’s death.

The New York Times, noting that other living presidents remained loyal to the Union, called Tyler “the most unpopular public man that had ever held any office in the United States.” The paper went on, sneering:

“He ended his life suddenly, last Friday, in Richmond — going down to death amid the ruins of his native State. He himself was one of the architects of its ruin; and beneath that melancholy wreck his name will be buried, instead of being inscribed on the Capitol’s monumental marble, as a year ago he so much desired.”

Then the Times dealt a final blow:

“It will be remembered that Mr. TYLER’s mansion at Hampton, over which he hoisted the rebel flag last Spring, has been for some time occupied as quarters by our troops.”

Ouch.

Tyler’s legacy hasn’t particularly improved since his death. His fellow presidents express little admiration for their predecessor who betrayed his country. Harry Truman called him “one of the presidents we could have done without.” Theodore Roosevelt described Tyler as “a politician of monumental littleness.”

In his biography of John Tyler’s life, Robert Seager wrote: “His countrymen generally remember him, if they have heard of him at all, as the rhyming end of a catchy campaign slogan.”

But history should remember Tyler for two things. One, he cemented the idea that the vice president becomes the president, if the president dies. And two, he betrayed the country which he had sworn to serve.

And I think the donald said: :”John Tyler was one of our greatest Presidents”.

LikeLike