By Kaleena Fraga

On July 24, 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt gave one of his iconic radio addresses to the nation. In this address, Roosevelt referenced: “the hundred days which had been devoted to the starting of the wheels of the New Deal.”

His administration had had a productive couple of months. In the first 100 days of his term—as the Great Depression raged—Roosevelt and his team jammed 15 bills through Congress. In the future, the first 100 days of subsequent presidents would be examined closely.

So, what were FDR’s first 100 days like? What did he accomplish?

FDR’s First 100 Days in Office

Like Joe Biden, Franklin Delano Roosevelt took the helm of a country in crisis. In his first year in office, the American unemployment rate would reach its peak at around 25%. Over 12 million Americans were out of work.

Roosevelt equated fighting the Great Depression to fighting a war—an analogy that has also been used to describe the fight against coronavirus. Roosevelt said:

“I shall ask the Congress for the one remaining instrument to meet the crisis — broad Executive power to wage a war against the emergency, as great as the power that would be given to me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.”

Then he got to work.

Two days after his inauguration on March 4th, 1933, Roosevelt declared a national “bank holiday” to stem the tide of people trying to withdraw their money from failing banks. A few days later, he signed the Emergency Banking Act, which allowed banks to reopen if the government found them sound. Aware that the country could plunge into deeper crisis, Congress rushed the passage of the bill—even though there were no available copies to read.

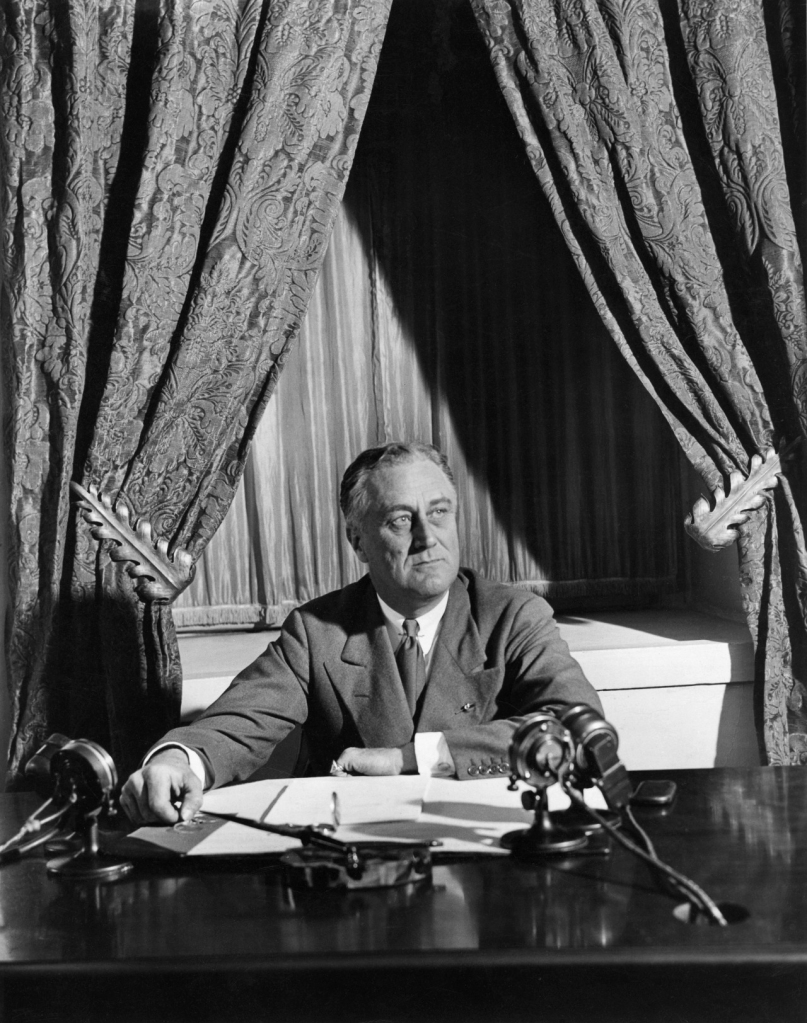

On March 12th, FDR gave his first “fireside chat”—a radio address to the nation to explain his actions and to reassure Americans that it was safe to put their money in the bank.

“My friends,” Roosevelt said, “I want to talk for a few minutes with the people of the United States about banking—to talk with the comparatively few who understand the mechanics of banking, but more particularly with the overwhelming majority of you who use banks for the making of deposits and the drawing of checks.”

He reassured the country that it was: “Safer to keep your money in a reopened bank than under the mattress.”

FDR’s direct communication worked. In the following weeks, Americans returned nearly a billion dollars to banks that the governments had declared sound. Raymond Moley, one of Roosevelt’s closest aides, remarked that “capitalism was saved in eight days.”

Roosevelt didn’t stop there. In the next 100 days—technically, 105—his administration would usher 15 bills through Congress. They had a three-pronged goal: to boost employment, to help Americans in rural states, and to enact financial reforms.

A year later, unemployment started to drop and the country’s GDP began to rise. Arguably, it would take the ultimate stimulus of WWII—and the ramping up of production—to end the Great Depression. But FDR brought relief to millions of Americans.

In his actions, FDR not only helped steer the United States away from crisis—he redefined the role of the federal government. Roosevelt believed it was a matter of “social duty” for the government to help where it could. His predecessor, Herbert Hoover, was well aware of this. A free-market capitalist, Hoover remarked that the 1932 election between Roosevelt and himself would be not: “a contest between two men” but “two philosophies of government.”

Roosevelt also erected a bar for future presidents to scale. His successors would face pressure to have a productive 100 days in office like he had.

What Have Other Presidents Done In the First 100 Days?

John F. Kennedy was well-aware of the pressure of his first 100 days when he became president in 1961. In his inauguration, Kennedy said: “All this will not be finished in the first one hundred days. Nor will it be finished in the first one thousand days, nor in the life of this administration, nor even perhaps in our lifetime on this planet. But let us begin.”

George W. Bush reluctantly attended a luncheon with lawmakers to mark his first 100 days in office—Bush saw 100 days as an arbitrary milestone—and noted: “We’ve had some good debates, we’ve made some good progress, and it looks like we’re going to pass some good law.”

Barack Obama, like Kennedy, remarked that the first 100 days of a presidency were only a starting point. “The first hundred days is going to be important, but it’s probably going to be the first thousand days that makes the difference.”

Obama—like Roosevelt—had inherited a country in crisis, in the throes of the Great Recession. Obama’s first 100 days in office were pretty productive—he passed the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act in January, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act in February, and started laying the groundwork to pass his healthcare bill.

—

Presidents may dislike the pressure to perform in their first 100 days—but it looks like the standard is here to stay. Simply Google “100 days” and you’ll find a glut of articles speculating about what Biden’s will look like. Time, US News, Fidelity, and NPR have all run pieces about Biden’s agenda for his first 100 days in office.

Ultimately, Kennedy had a point. The first 100 days of a presidency may set the tone. But presidencies are judged as part of a whole that’s much longer than 100 days—or even four or eight years.