By Kaleena Fraga

At a White House Christmas party this week, President Trump mused out loud that he might run for president again in 2024.

“It’s been an amazing four years,” Mr. Trump said. “We are trying to do another four years. Otherwise, I’ll see you in four years.” The crowd cheered.

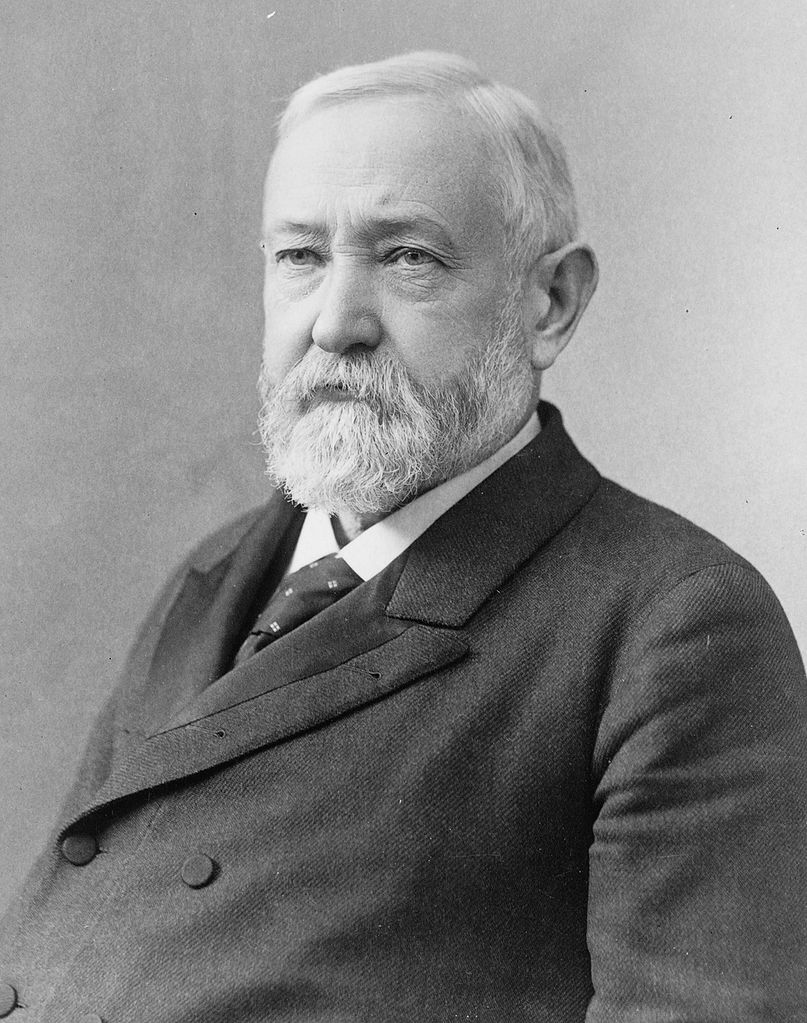

If he were to run, and win, Donald Trump would become only the second president to serve two, non-consecutive terms. The first was Grover Cleveland, who was elected in 1884 and 1892, making him the 22nd and 24th president of the United States.

Let’s get into it!

The Election of 1884: Cleveland vs. Blaine

Grover Cleveland’s second election in 1892 certainly sets him apart in American history. But his first election was also noteworthy. In 1884, Cleveland became the first Democrat to be elected since the Civil War.

Since Lincoln, the Republicans had retained the White House. But power seemed prime to shift in 1884. Cleveland—the governor of New York—was in a good position to carry his state. If he could win New York and the entire south, he could win the presidency.

What’s more, many Republicans disliked their own nominee: James G. Blaine. Anti-Blaine Republicans, called Mugwumps, were the #NeverTrumpers of their day. Blaine stood accused of using his office as Speaker of the House to obtain favors from the railroads. Mugwumps would not support their party’s nominee, warning that his election would “dishonor the nation.”

The Mugwumps made it clear that they were still Republicans—just not Blaine Republicans. “We do not ally ourselves with the Democratic party, still less sanction or approve its past” —a shot over the bow and a nod of the head toward the Civil War — “but its present candidate has proved his fidelity to the principles we avow…he commands and will receive our support.”

Democrats gleefully piled on. Soon, their campaign slogan echoed throughout the country: “Blaine, Blaine, James G. Blaine, The continental liar from the State of Maine.”

Republicans were not going to go without a fight. When it came out that Cleveland may have fathered an illegitimate child, they attacked with a slogan of their own: “Ma, Ma, Where’s My Pa?”

Cleveland admitted that he could be the child’s father. His supporters argued that, “Mr. Blaine has been delinquent in office but blameless in public life, while Mr. Cleveland has been a model of official integrity but culpable in personal relations.”

The solution? Elect Cleveland and his integrity to the presidency—let Blaine return to his innocent public life.

A supporter of Blaine’s made things worse at a rally in New York City. Attempting to rouse the crowd, he accused the Democrats of being the party of “rum, Romanism, and rebellion.” The city’s Irish Catholics, whom Blaine hoped to court, soured on the Republican candidate. (Blaine was not present—but did not denounce the remark, either.)

Antipathy toward Blaine and Cleveland’s New York roots helped propel the latter to the presidency. It was a narrow victory. Cleveland won New York—and, therefore, the presidency— by only 1,000 votes.

After the election, Democrats commandeered the Republican’s campaign slogan. “Ma, Ma, Where’s My Pa?” was now answered by: “Off to the White House, Ha, Ha, Ha!”

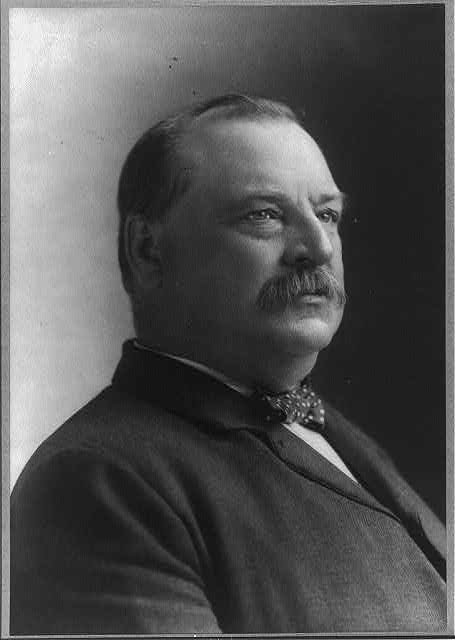

The Election of 1888: Cleveland vs. Harrison

In 1888, Cleveland faced Benjamin Harrison. Harrison was, in many ways, a more formidable foe than Blaine. He was a former Civil War general, a senator from Indiana, and the grandson of a president—William Henry Harrison, who is best known for dying one month into his presidency. Benjamin Harrison, however, had not been the party’s first choice. He won the nomination on the eighth ballot at the Republican convention.

Cleveland had also caused problems for himself. In December of 1887, he called on Congress to reduce high protective tariffs, believing them to be unfair to consumers. Cleveland was told that this would give the Republicans ammunition as they moved into 1888—tariffs were the issue of the day—but he didn’t care. “What is the use of being elected or re-elected unless you stand for something?” Cleveland asked.

Indeed, the election of 1888 focused on what the two men stood for—instead of their moral failings. Republicans attacked Cleveland for his position on tariffs and for his aggressive use of the presidential veto, including the veto of a bill which denied pension increases to Civil War veterans.

By this time, the era of Lincoln Republicans had ended. Republicans of the 1880s were the party of big business. They found Cleveland and his ideas about tariff reductions incredibly threatening. So, they barnstormed the country. Republicans told voters that the Democrats did not understand money and that Cleveland’s reelection would cause people to lose their jobs. They also heavily emphasized their candidate’s political lineage, with campaign slogans like “The Same Old Hat – It Fits Ben Just Right.” (Democrats responded with their own slogan: “His Grandfather’s Hat – It’s Too big for BEN.”)

In the end, Harrison won the election. Cleveland lost his crucial state of New York as well as Harrison’s Indiana, which resulted in a lopsided Harrison victory—Harrison won the Electoral College but Cleveland won the popular vote. (47.9 percent to 48.6 percent.) That puts Cleveland in league with only four other candidates who have won more votes but lost the presidency: Andrew Jackson (1824), Samuel Tilden (1876), Al Gore (2000), and Hillary Clinton (2016).

(For our purposes of comparing Cleveland to Trump, this is significant. Cleveland won the popular vote. Given Trump’s loss of both the Electoral College and the popular vote in 2020, it’s possible he’d face an uphill battle in 2024. Trump may, however, be interested to hear that the 1888 election was likely rife with corruption. Black votes were suppressed. Other votes were bought. In one anecdote, Harrison thanked Providence for his victory. His campaign manager, Mark Hanna, noted to a friend: “Providence hadn’t a damn thing to do with it. A number of men were compelled to approach the penitentiary to make him president.”)

As Cleveland left the White House, his wife Frances, turned to face the staff. “I want to find everything just as it is now when we come back again,” she said. “We are coming back just four years from today.”

Cleveland was down, but not out. Four years later, he’d run against Harrison for a second time.

The Election of 1892: Harrison vs. Cleveland

According to historian Heather Cox Richardson, the Republicans moved aggressively after the election to ensure their hold on power. They had, after all, controlled the White House for decades. So, how to avoid another showing by a Democrat like Cleveland?

Add new states! That was the plan—add six new states, creating a Republican firewall. In 1889, North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, and Washington joined the Union. In 1890, Idaho and Wyoming were established.

Republican operatives were sure this plan would work. But, as is wont in American politics, it backfired. In the 1890 midterm elections, the Democrats took the House of Representatives by a margin of 2:1. They swept to power bolstered by a bad economy and by the American West.

With the election of 1892 looming, Republicans threw their weight behind Harrison. But they weren’t happy with him. He could be cold and standoffish and refused to listen to advice. It’s possible that Harrison only ran for a second term out of spite—at the party convention, many Republicans tried to get James G. Blaine on the ticket instead of Harrison. Blaine refused.

After a quiet campaign, Cleveland swept to victory. For the first time since the Civil War, the Democrats won the presidency, the Senate, and the House.

We recently wrote about painful presidential transitions, and the Benjamin Harrison to Grover Cleveland transition deserves a place on that list. According to Richardson, it was the among the worst.

After his loss, Harrison threw up his hands. In Republican controlled newspapers, the embittered party told voters that Democrats didn’t know how to run the country—so everyone should take their money out of the stock market.

And thus began the Panic of 1893. Those who saw it coming begged Washington for help. But Harrison’s administration wouldn’t lift a finger. According to Harrison’s Treasury Secretary, they were only responsible for the economy until Cleveland’s inauguration.

In fact, the economy collapsed 10 days before Cleveland entered office. Cleveland was left to manage an economic crisis—which may have led him to regret returning to the presidency in the first place. According to the Miller Center, Cleveland left office a bitter man. When he died in 1908, his last words were “I have tried so hard to do right.”

—

What will happen in 2024? We don’t know—but it’s definitely too early for speculation. Or is it…?

Alas, some things never change; Trumpwumps unite!

LikeLiked by 1 person