By Kaleena Fraga

(to listen to a version of this piece in podcast form, click here)

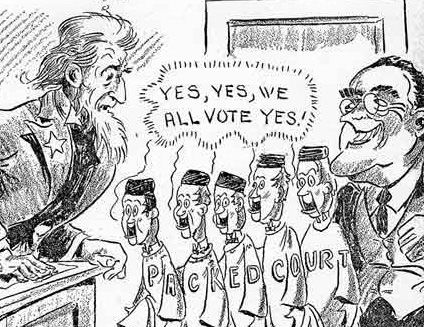

On February 5th, 1937, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt announced that he would attempt to expand the Supreme Court bench. His announcement incited instant outrage–Roosevelt’s opponents accused him of trying to pack the court so that he could push through his New Deal policies. Roosevelt’s plan was radical—he sought to completely reshape the court—but the idea of changing the number of justices is not, and indeed, Congress has adjusted the size of the Supreme Court six times in American history.

Originally, the Judiciary Act of 1789 ruled that there would be six justices. But when Thomas Jefferson swept to power in a Democratic wave that also put his party in Congress, the lame-duck Federalist Congress voted to reduce the number of justices to five. When the next Congress was sworn in, they repealed this decision, keeping the court at six justices. In Jefferson’s second term, they added a seventh, affording Jefferson the opportunity to appoint someone to the bench.

Thirty years later the size of the court changed again. Congress increased the court to nine justices, which gave Andrew Jackson the opportunity to hand-pick the two additions to the Supreme Court.

Change came again in the 1860s. This was a a turbulent time for the nation, and the Supreme Court. In the midst of the Civil War the court expanded yet again to an all-time high of ten justices–this time to protect an anti-slavery/pro-Union majority. But when Andrew Johnson became president following Lincoln’s assassination, the Republican Congress reduced the size of the court to protect it from a Democratic president. The court shrank from ten justices to seven. Congress effectively removed Johnson’s ability to appoint any justices. Then when Ulysses S. Grant became president in 1868 after Johnson left office, Congress voted to expand the court to nine justices. For many people in 1937 when Roosevelt made his pronouncement, nine justices felt like a norm—like an unchangeable fact of the judicial system.

Roosevelt’s plan, however, was not as simple as expanding the court. He wanted to enforce rules to make justices retire at 70, and, if they refused, give himself the power to appoint associate justices who could vote in their stead. This would effectively give him the power to sculpt the court, and to ensure the legality of his New Deal legislation.

FDR had had a productive first term, and had won reelection by a stunning margin. (He had won the largest popular vote margin in American history, and the best electoral vote margin since James Monroe ran unopposed). But the justices on the Supreme Court had publicly expressed opposition to Roosevelt’s policies. Because six of the nine were over 70, Roosevelt’s plan would boot them off the bench. His argument was that they had grown too old to do their work, and that they had fallen behind. A lifetime term, Roosevelt said, “was not intended to create a static judiciary. A constant and systematic addition of younger blood will vitalize the courts.”

But Roosevelt’s statement that the Court was behind on its work wasn’t true. His plan was met with roaring opposition as letters poured in from around the country. Even his vice president, John Nance Gardner, expressed displeasure as the plan was read aloud in Congress, holding his nose and making a thumbs-down gesture. In the Senate, Roosevelt could only gather 20 votes for his plan.

Roosevelt wasn’t able to make any changes to the Supreme Court. Yet, perhaps because of his maneuvering, he convinced one justice, Owen Roberts, to switch his vote to support many New Deal policies.

Given the outrage at the time of Roosevelt’s proposal, and it’s ultimate failure, it’s no wonder that the idea of changing the composition of the court is often met with distrust and derision. But there is nothing in the Constitution that says the Supreme Court has to stay at nine justices, and, indeed, it has fluctuated between six and ten throughout American history. Perhaps Roosevelt could have succeeded if he had merely attempted to expand the Court as Congress did under Jefferson, Jackson, and Grant.

Today, with the retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy, the Supreme Court’s swing vote, the idea of changing the composition of the court has begun to gain traction among Democrats. As many liberals look down the barrel of thirty or forty years of conservative Supreme Court decisions, expanding the court to allow the appointment of more liberal justices could be the remedy they are seeking.

Good back-up plan; Trump’s right-wing conservative nominee, after a grand-standing Senate Judicial Committee confirmation hearing (with bland & vague assertions by the nominee to follow the law) [why don’t the Senators ask questions like: what books are you reading; what do you do for recreation; what is your most admired historical person & why, etc] will likely get confirmed, unless Senator Collins & the Senator from Alaska & a few other Republicans – Rand Paul? – vote against; then the Democrats somehow take majority control of the Senate & House after the November elections, and then increase the size of the Supreme Court and somehow confirm more balanced progressive jurists – problem is Trump will still be President!

LikeLike

But wait…there’s more…Mueller indicts Trump! then after the Senate & House makeup changes in November 2018, Trump is impeached and removed, or more likely resigns saying “It’s a Witch Hunt; and I won’t give Congress the pleasure to impeach me”; then Pence becomes President…and throws in the towel a little and nominates more balanced & rational jurists to the Court; Ok, now I feel better…or do I?

LikeLike

A switch in time saved nine! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person