By Aaron Bauer

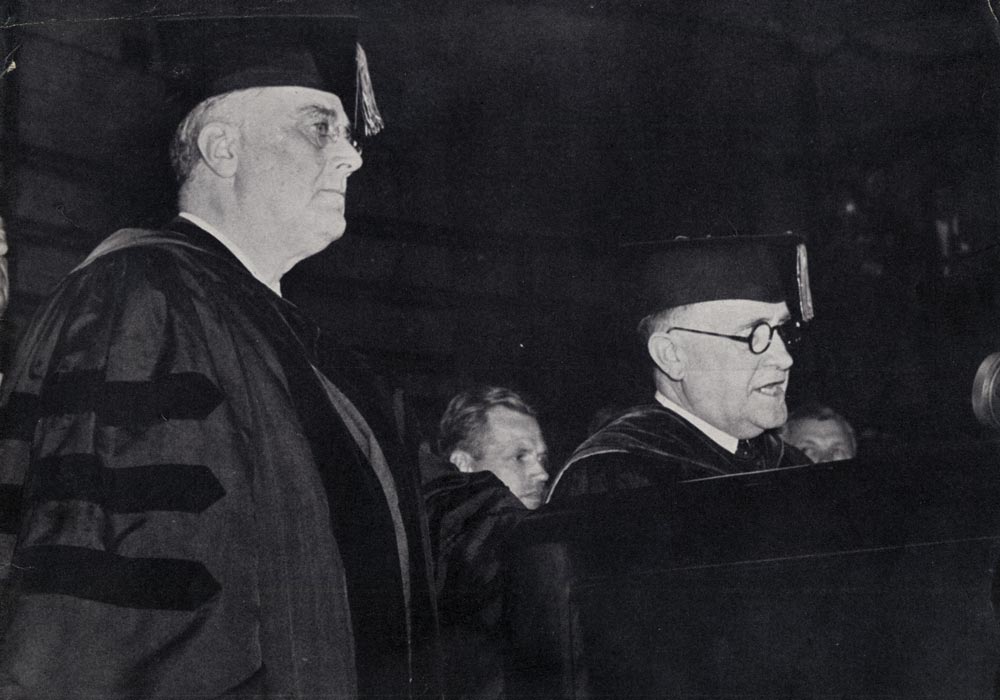

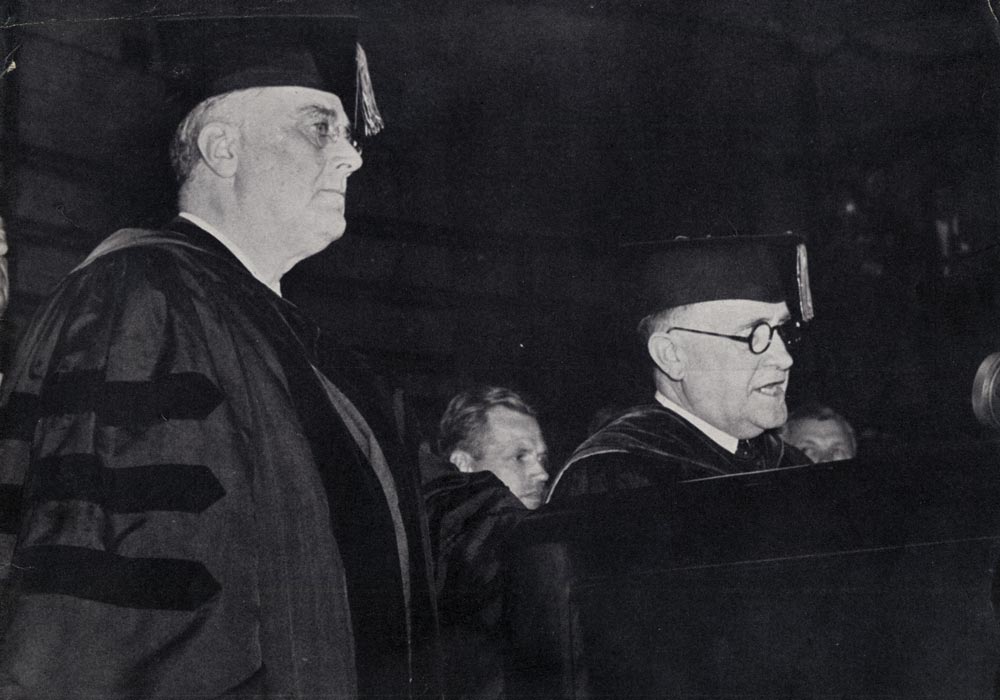

June 1940 was a dark time in human history. After the conquest of Poland in October 1939, Hitler unleashed his armies on Western Europe in the spring of 1940. Denmark and Norway fell quickly, Belgium was overrun, and by early June, France was near total collapse. On June 10th, Italy entered the war on Germany’s side, declaring war on its former allies France and Britain. That same day, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt  was scheduled to address the graduating class at the University of Virginia. He used the opportunity to comment on the events transpiring across the Atlantic. Roosevelt condemned Italy’s aggression as a stab in the back, and spoke of the dangers of a world dominated by the brutal fascism of Hitler and Mussolini. Going a step further, the president declared that the U.S. would “extend to the opponents of force the material resources of this nation; and, at the same time, we will harness and speed up the use of those resources in order that we ourselves in the Americas may have equipment and training equal to the task of any emergency and every defense.”

was scheduled to address the graduating class at the University of Virginia. He used the opportunity to comment on the events transpiring across the Atlantic. Roosevelt condemned Italy’s aggression as a stab in the back, and spoke of the dangers of a world dominated by the brutal fascism of Hitler and Mussolini. Going a step further, the president declared that the U.S. would “extend to the opponents of force the material resources of this nation; and, at the same time, we will harness and speed up the use of those resources in order that we ourselves in the Americas may have equipment and training equal to the task of any emergency and every defense.”

To most Americans today, Roosevelt’s statement would seem natural, expected even, in the face of unprovoked aggression. Yet, the profound isolationism that followed the utter implosion of Woodrow Wilson’s internationalist vision in 1919 still dominated U.S. politics in 1940. From 1920 onwards, the financial heft of Wall Street and the material resources of a continent ensured America’s place as an economic giant, but disengagement and disinterest were the order of the day when it came to global affairs. Throughout the next two decades, both the American people and their government saw events beyond the nation’s shores as none of their concern. Congress translated this sentiment into law in the form of immigration restrictions, tariffs, and even repeated proposals for a constitutional amendment requiring a popular referendum for any declaration of war. As totalitarian wars of conquest raged in Europe and Asia, Roosevelt had to contend with a dominant political faction at home who believed taking sides the height of folly.

In his June 10 address, Roosevelt met the isolationists head on:

Some indeed still hold to the now somewhat obvious delusion that we of the United States can safely permit the United States to become a lone island, a lone island in a world dominated by the philosophy of force.

Such an island may be the dream of those who still talk and vote as isolationists. Such an island represents to me and to the overwhelming majority of Americans today a helpless nightmare of a people without freedom—the nightmare of a people lodged in prison, handcuffed, hungry, and fed through the bars from day to day by the contemptuous, unpitying masters of other continents.

Leading isolationists of both parties fired right back. Roosevelt’s pronouncements were “nothing but dangerous adventurism” in the opinion of North Dakota Republican Gerald Nye. Massachusetts Democrat David Walsh decried the idea of sending armaments overseas to aid those fighting Hitler: “I do not want our forces deprived of one gun, or one bomb or one ship which can aid that American boy whom you and I may someday have to draft.” Aviation celebrity and arch isolationist Charles Lindbergh derided the June 10 speech as “defense hysteria” and argued that foreign invasion was only a threat if “the American people bring it on through their own quarreling and meddling with affairs abroad.”

This was not the first time Roosevelt and isolationists had come to rhetorical blows. When Japan began its bloody conquest of China in 1937, Roosevelt called for a “quarantine” of aggressor nations. Isolationists in Congress responded by threatening impeachment. Realizing the strength of the opposition, Roosevelt resolved to take an incremental approach. The president was very conscious of the risk in getting too far ahead of public opinion. As he put it to an aide, “It’s a terrible thing to look over your shoulder when you are trying to lead—and find no one there.”

Despite the challenges, by mid-1940 Roosevelt’s incremental strategy had begun to show signs of life. Though the overwhelming majority of the public continued to oppose direct involvement in the war, polls showed two-thirds now supported some kind of aid to Britain. Mainstream newspaper editors, who enjoyed far more influence in 1940 than the print media of 2018, came around and began to advocate for sending aid. Dr. Seuss, who in the war years drew political cartoons for the New York paper PM, mocked Republican isolationists as half-elephant/half-ostrich creature with its head in the sand (the GOPstrich). As Americans bickered and dawdled, the war in Europe was going from bad to worse. The French surrender on June 22nd left Britain as the sole nation still in the fight against Hitler. German aircraft pounded British cities and there were fears of an imminent German invasion of the British Isles. The new British Prime Minister Winston Churchill believed that getting America into the war was his country’s only hope for victory. In a defiant speech to the House of Commons that June, he promised that Britain would fight on “until, in God’s good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the old.”

to worse. The French surrender on June 22nd left Britain as the sole nation still in the fight against Hitler. German aircraft pounded British cities and there were fears of an imminent German invasion of the British Isles. The new British Prime Minister Winston Churchill believed that getting America into the war was his country’s only hope for victory. In a defiant speech to the House of Commons that June, he promised that Britain would fight on “until, in God’s good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the old.”

In the face of the crisis, Roosevelt knew he must act decisively. The U.S. desperately needed to build up its army, which at the beginning of 1940 was approximately one twentieth the size of Germany’s and armed with weapons decades out of date. By the end of World War I, America had fielded the fourth largest army in the world. Between post-war disarmament and an isolationist Congress opposed to military spending and determined to shut down weapons manufacturers, the U.S. army had slid to eighteenth by 1939, just ahead of the Portuguese. To give the U.S. the time it needed to rearm, Britain had to be kept in the war. Further complicating matters, 1940 was a presidential election year, and Roosevelt had to undertake all this while running for reelection to an unprecedented third term. It would take every bit of his considerable political skill to see it done.

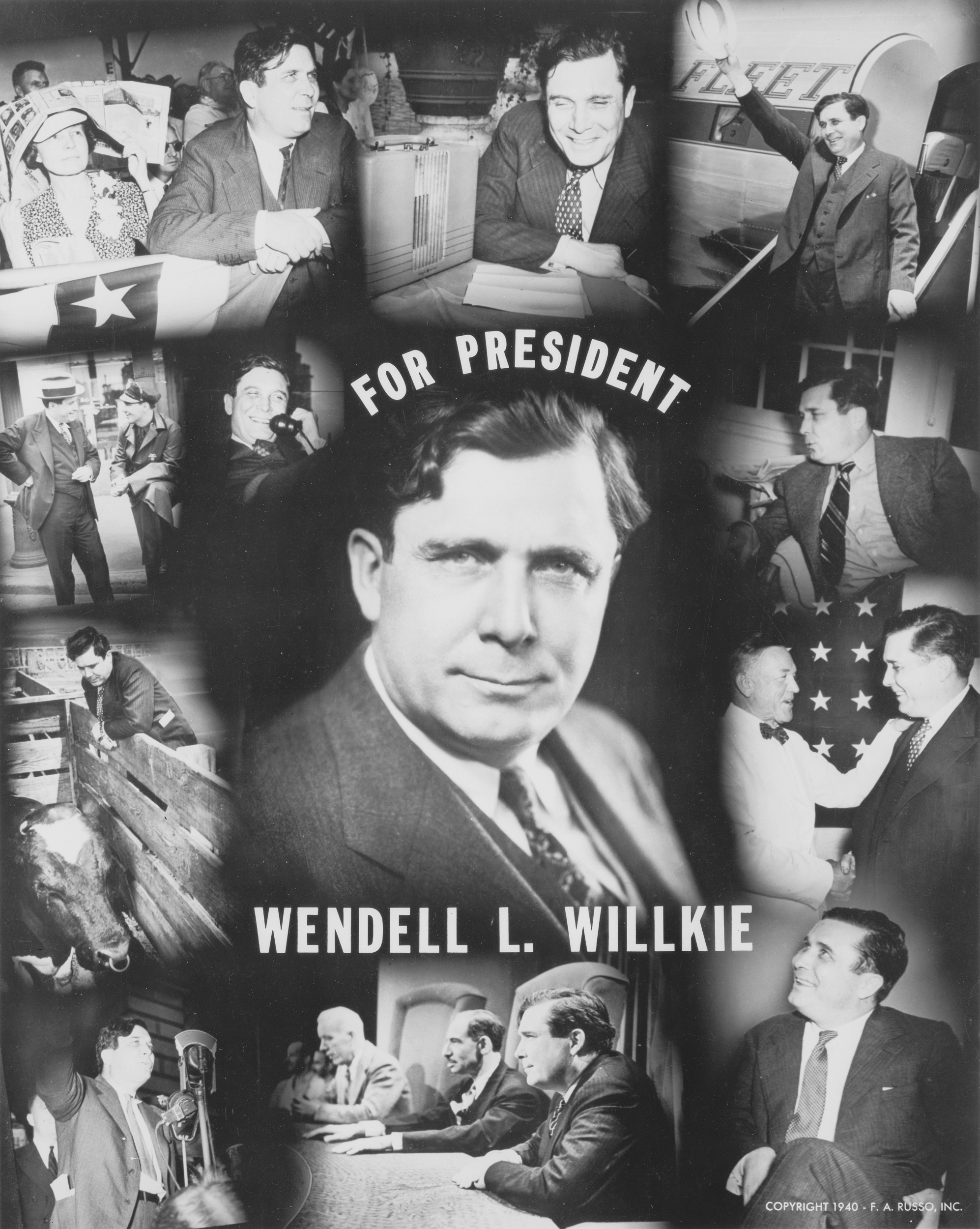

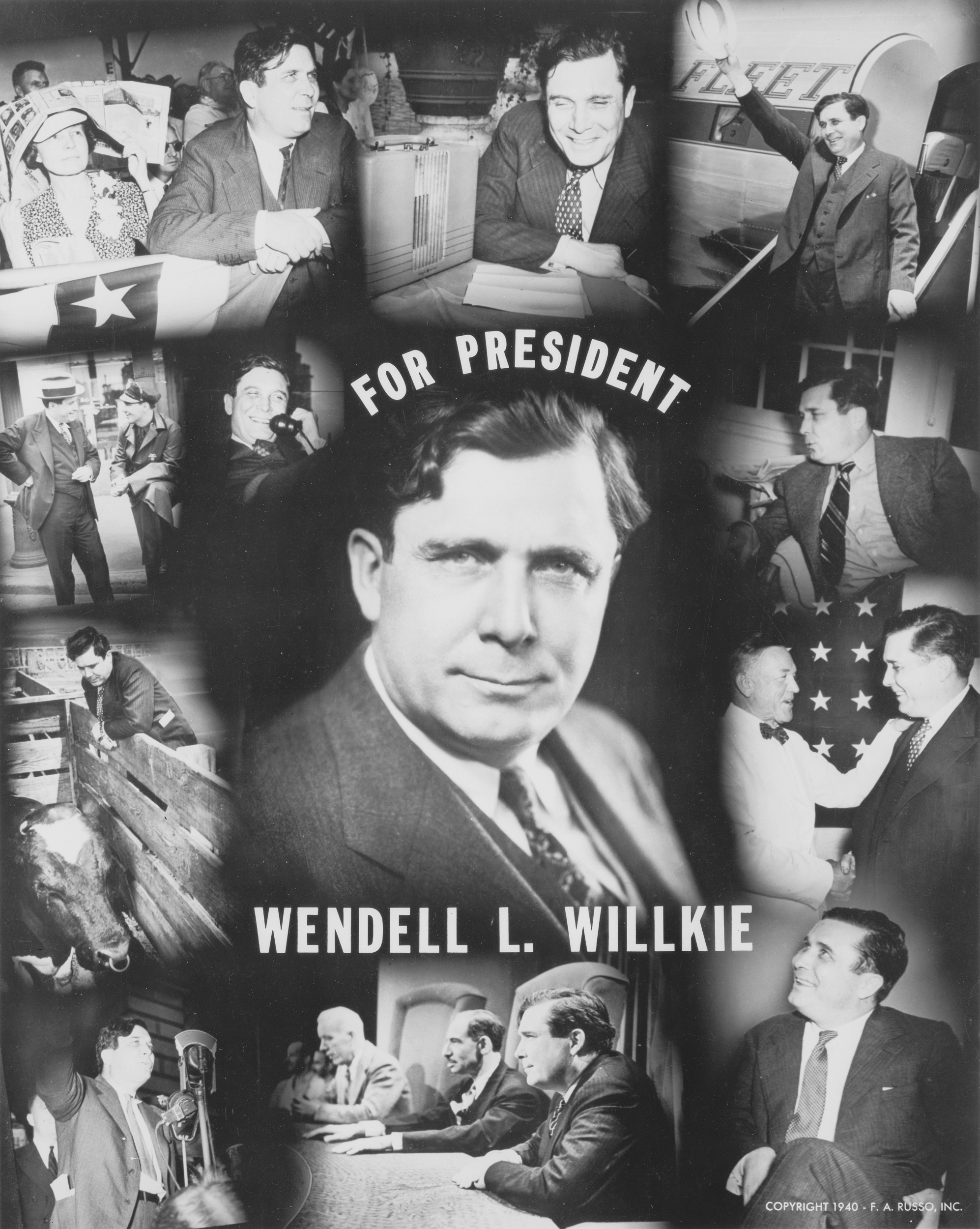

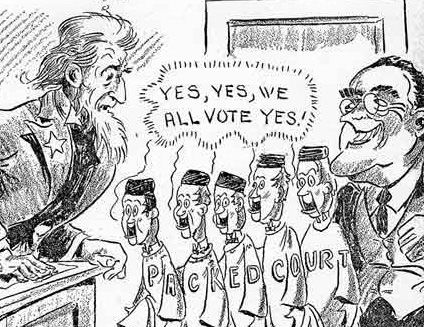

One of Britain’s most urgent needs was additional ships to defend her shores and commerce. Roosevelt negotiated with Churchill to trade unused U.S. destroyers for leases establishing military bases on a number of British territories in the Western hemisphere. Knowing there was no time for a lengthy fight in Congress, Roosevelt simply bypassed it and announced that the deal had been made. With characteristic deviousness, Roosevelt tried to steal some media attention from his 1940 opponent Wendell Willkie by making this announcement at the same time as Willkie’s speech accepting the Republican nomination. While Roosevelt was praised for getting the better end of the deal with the British, his end-run around Congress brought on full-throated condemnation from his critics. Willkie called the move “the most dictatorial and arbitrary of any President in the history of the U.S,” and the St. Louis Post Dispatch proclaimed “Mr. Roosevelt today committed an act of war. He also becomes America’s first dictator.” Public criticism aside, Roosevelt had taken an important step in forging a transatlantic alliance against Hitler, and U.S. arms sales became a crucial lifeline for the British.

Preparing the U.S. military required a far greater act of political courage. With the Army’s need to begin training an army of more than a million men as soon as possible, Roosevelt took the risky step of vigorously supporting the first-ever peacetime draft in U.S. history. On this issue, the president received key support from an unexpected quarter: Wendell Willkie. Though critical of Roosevelt’s methods and parts of the New Deal agenda, Willkie differed from many Republican elected officials in his belief that “we cannot brush the pitiless picture of their [the stricken people of Europe] destruction from our eyes or escape the profound effects of it upon the world in which we live,” and that “some form of selective service is the only democratic way in which to assure the trained and competent manpower we need in our national defense.” The selective service bill made it through Congress with bipartisan support, and Roosevelt, over the objections of his advisers, began conscription just a week before voters went to the polls. America would have a military capable of meeting the threats abroad.

Neither conscription nor Willkie’s charisma proved able to shake Roosevelt’s political coalition, and 1940 saw the nation’s first (and only) election of a third-term president. His electoral victory did not, however, signal the defeat of the forces of isolationism. September 1940 saw the formation of the America First Committee, which would become one of the largest anti-war organizations in U.S. history. Its spokesperson, Charles Lindbergh, clashed frequently with the Roosevelt administration. Largely based in the Midwest, the Committee argued that staying out of the war was vital to the preservation of American democracy and that the sending of aid weakened the U.S. and risked drawing the country into the war. Roosevelt had his own case to make, and in December delivered the sixteenth “fireside chat” radio address of his presidency to put it before the American people. If the Axis is victorious, he argued, Americans would be “living at the point of a gun.” Roosevelt pointed out the futility of negotiating, that experience had “proven beyond doubt that no nation can appease the Nazis. No man can tame a tiger into a kitten by stroking it. There can be no appeasement with ruthlessness. There can be no reasoning with an incendiary bomb.” America’s role was clear, he declared, “We must be the great arsenal of democracy. For us this is an emergency as serious as war itself.”

As 1940 drew to a close a new emergency arose: the financial underpinnings of the American aid to Britain were in dire straights. The previous year, Roosevelt had pried from Congress authorization for “cash and carry” arms sales to Britain. But after more than a year of war, Britain had nearly exhausted its ability to pay hard cash. The mess of debts that had languished after the First World War (Britain still owed the US $4.4 billion in 1934) killed any political appetite in the U.S. to loan the British the funds they needed. A creative solution was required, and fast, if American weapons and supplies were to remain on the front lines of the war. The solution came to Roosevelt, almost fully formed, while he was enjoying a post-election vacation cruise. The Lend-Lease policy, as it came to be called, was a classic Roosevelt workaround. The U.S. would lend, rather than sell, Britain the equipment it needed for the duration of the war, with the expectation that it would either be returned or Britain would pay to replace it. The president’s staff were stunned by his sudden insight. Labor Secretary Frances Perkins called it a “flash of almost clairvoyant knowledge and understanding.” “He did not seem to talk much about the subject in hand, or to consult the advice of others, or to ‘read up’ on it,” recounted speechwriter Bob Sherwood. “One can only say that FDR, a creative artist in politics, had put in his time on this cruise evolving the pattern of a masterpiece.”

Conceiving of Lend-Lease was one thing, but getting it through Congress was something else entirely. Roosevelt’s first step was to explain the idea to the public. In a press conference, he used an accessible and compelling metaphor:

Well, let me give you an illustration: Suppose my neighbor’s home catches fire, and I have a length of garden hose four or five hundred feet away. If he can take my garden hose and connect it up with his hydrant, I may help him to put out his fire. Now, what do I do? I don’t say to him before that operation, “Neighbor, my garden hose cost me $15; you have to pay me $15 for it.” What is the transaction that goes on? I don’t want $15—I want my garden hose back after the fire is over. All right. If it goes through the fire all right, intact, without any damage to it, he gives it back to me and thanks me very much for the use of it. But suppose it gets smashed up—holes in it—during the fire; we don’t have to have too much formality about it, but I say to him, “I was glad to lend you that hose; I see I can’t use it any more, it’s all smashed up.” He says, “How many feet of it were there?” I tell him, “There were 150 feet of it.” He says, “All right, I will replace it.” Now, if I get a nice garden hose back, I am in pretty good shape.

The President’s critics were having none of it. Such an arrangement would inevitably entangle the country in foreign wars. Ohio Republican Senator Robert Taft, the son of former president William Howard Taft, believe that Lend-Lease would give Roosevelt dictatorial powers “to carry on a kind of undeclared war all over the world.” Charles Lindbergh characterized the policy as “another step away from democracy and another step closer to war.” But during the weeks of hearings Congress held in early 1941, the law’s supporters won the argument—public support rose from 50 percent to 61 percent and Roosevelt signed it into law in March 1941. In a time when totalitarian regimes were ascendent across much of the world, Roosevelt saw this process as exemplifying the strength of a democratic system: “Yes, the decisions of our democracy may be slowly arrived at. But when the decision is made, it is proclaimed not with the voice of one man but with the voice of 130 million.”

Even as the passage of Lend-Lease allowed for continued and increasing U.S. aid to Britain, the American public and its government remained deeply divided over the nation’s path. German submarines were sinking a lot of American supplies in transit, but public support for U.S. Navy convoys to protect them remained lukewarm (52 percent in May). Enough isolationists in Congress pledged “unalterable opposition” to convoys to block any possible action. Furthermore, large majorities opposed getting further involved, with 79 percent of Americans expressing desire to stay out of the war and 70 percent believing Roosevelt was doing enough or too much for Britain. In late May, Roosevelt exercised one of the few remaining available options and used his authority to declare an “unlimited national emergency.” This granted him additional unilateral authority to prepare the country for war by increasing the size of the military and exercising more control over the defense industry. Roosevelt announced this move in a national radio address in which he cast the war in Europe not as a local squabble, but as “a war for world domination.” He painted a bleak picture of a world culturally and economically dominated by Nazi Germany, and implored Americans to realize the danger: “Some people seem to think that we are not attacked until bombs actually drop in the streets of New York or San Francisco or New Orleans or Chicago, but they are simply shutting their eyes to the lesson that we must learn from the fate of every nation that the Nazis have conquered…”

By the summer of 1941, Roosevelt felt he had reached the limit of where he could lead the public. When Germany launched its massive invasion of Soviet Russia in June 1941, Roosevelt intervened again and again to break through a reluctant bureaucracy and get aid flowing to the war’s Eastern front. Missouri Democrat Bennett Clark spoke for many when he described Nazism versus Communism as “a case of dog eat dog.” “Stalin is as bloody-handed as Hitler,” Bennett said, “I don’t think we should help either one.”

It was the German U-boats, just as in 1917, that swung public opinion decisively in favor of war. Repeated sinkings of U.S. merchant and military ships throughout 1941 that killed more than a hundred American sailors convinced a majority that war was necessary. Support for the arming of merchant ships (forbidden by a Neutrality Act passed by Congress in the 1930s) rose from 30 percent in April 1941 to 72 percent by the fall. Even so, isolationists in the Senate were able to stall a Neutrality Act revision. Roosevelt again took to the airwaves, announcing in a September fireside chat a “shoot-on-sight” policy. “No matter what it takes, no matter what it costs, we will keep open the line of legitimate commerce in these defensive waters…. Let this warning be clear. From now on, if German or Italian vessels of war enter the waters, the protection of which is necessary for American defense, they do so at their own peril…. When you see a rattlesnake poised to strike, you do not wait until he has struck before you crush him. These Nazi submarines and raiders are the rattlesnakes of the Atlantic.” With public opinion continuing to shift (a September 1941 Gallup poll showed that 70 percent agreed that the defeat of Germany was more important than keeping America out of war), the revision eventually passed the Senate by a small margin.

Roosevelt once said “I am a juggler. I never let my right hand know what my left hand does.” Across 1939 to 1941, he indeed performed a remarkable feat of political juggling. The president removed legal and political barriers to supplying military aid to the nations fighting Hitler, played a role in the complete reversal of public opinion on the importance of defeating Germany, and rebuilt the U.S. military from a state of near complete neglect, all the while dealing with entrenched isolationism in Congress, weathering attacks from America First, and winning the only third term in U.S. history. Roosevelt’s public leadership, along with German submarine warfare and the news of the destruction wrought by Hitler’s armies relayed by American journalists in Europe, emotionally prepared the U.S. for war. Though it was Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and Hitler’s subsequent declaration of war that brought the U.S. into the Second World War, Roosevelt’s dogged, incremental efforts to overcome isolationism were essential to prevent Axis victory in the war’s opening years. This same persistence in building up the nation’s army, navy, and military production saved precious months and years when the time came to truly get into the fight. Roosevelt had succeeded in making America an arsenal of democracy.

Sources:

No Ordinary Time by Doris Kearns Goodwin

American Warlords by Jonathan W. Jordan

The Presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt by George McJimsey

The American Presidency Project by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley

was scheduled to address the graduating class at the University of Virginia. He used the opportunity to comment on the events transpiring across the Atlantic. Roosevelt condemned Italy’s aggression as a stab in the back, and spoke of the dangers of a world dominated by the brutal fascism of Hitler and Mussolini. Going a step further, the president declared that the U.S. would “extend to the opponents of force the material resources of this nation; and, at the same time, we will harness and speed up the use of those resources in order that we ourselves in the Americas may have equipment and training equal to the task of any emergency and every defense.”

was scheduled to address the graduating class at the University of Virginia. He used the opportunity to comment on the events transpiring across the Atlantic. Roosevelt condemned Italy’s aggression as a stab in the back, and spoke of the dangers of a world dominated by the brutal fascism of Hitler and Mussolini. Going a step further, the president declared that the U.S. would “extend to the opponents of force the material resources of this nation; and, at the same time, we will harness and speed up the use of those resources in order that we ourselves in the Americas may have equipment and training equal to the task of any emergency and every defense.” to worse. The French surrender on June 22nd left Britain as the sole nation still in the fight against Hitler. German aircraft pounded British cities and there were fears of an imminent German invasion of the British Isles. The new British Prime Minister Winston Churchill believed that getting America into the war was his country’s only hope for victory. In a defiant speech to the House of Commons that June, he promised that Britain would fight on “until, in God’s good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the old.”

to worse. The French surrender on June 22nd left Britain as the sole nation still in the fight against Hitler. German aircraft pounded British cities and there were fears of an imminent German invasion of the British Isles. The new British Prime Minister Winston Churchill believed that getting America into the war was his country’s only hope for victory. In a defiant speech to the House of Commons that June, he promised that Britain would fight on “until, in God’s good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the old.”

On October 3rd, 1921, Taft finally realized his ultimate goal and was appointed as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court by President Warren Harding. “This is,” Taft declared, “the greatest day of my life.”

On October 3rd, 1921, Taft finally realized his ultimate goal and was appointed as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court by President Warren Harding. “This is,” Taft declared, “the greatest day of my life.” beautify the city, and ordered 2,000 cherry trees from Japan as part of this effort. Taft too forever changed the landscape of the capitol. He lobbied Congress to put aside funds for a new Supreme Court building–the one we know today–moving the justices out of the old Senate Chamber and into a building of their own. Taft

beautify the city, and ordered 2,000 cherry trees from Japan as part of this effort. Taft too forever changed the landscape of the capitol. He lobbied Congress to put aside funds for a new Supreme Court building–the one we know today–moving the justices out of the old Senate Chamber and into a building of their own. Taft

President Barack Obama

President Barack Obama

of political leadership.” Eight years

of political leadership.” Eight years

Schoumatoff was standing at her easel painting the president when something in his demeanor changed. She later recalled: “He looked at me, his forehead furrowed in pain, and tried to smile. He put his left hand up to the back of his head and said, ‘I have a terrible pain in the back of my head.’ And then he collapsed.”

Schoumatoff was standing at her easel painting the president when something in his demeanor changed. She later recalled: “He looked at me, his forehead furrowed in pain, and tried to smile. He put his left hand up to the back of his head and said, ‘I have a terrible pain in the back of my head.’ And then he collapsed.” in his own right. Although his approval rating hovered in the

in his own right. Although his approval rating hovered in the