By Kaleena Fraga

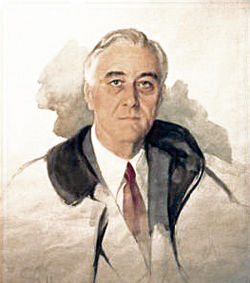

On this day in 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt gave the first of his famous fireside chats.

(to listen to this piece in podcast form click here)

It had never been done before. Or, it had, but not like this. On March 12, 1933, sixty million Americans listened to Roosevelt’s first radio address. Thus began a tradition that continued throughout Roosevelt’s presidency. The “fireside chats,” as journalist Robert Trout coined them, became a cornerstone of American life, as the country struggled with the Great Depression and toppled towards war.

Roosevelt wasn’t the first president to use radio to communicate with the country. Calvin Coolidge had given the first ever White House radio address, when he eulogized Warren G. Harding. Herbert Hoover had also used radio, both as a campaign tool and to give radio addresses, but he came across as much more formal than Roosevelt.

For example, during a radio address that Hoover gave on the anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday, February 12, 1931, a little over a year since the markets had crashed, Hoover started like this:

“The Federal Government has assumed many new responsibilities since Lincoln’s time, and will probably assume more in the future when the States and local communities cannot alone cure abuse or bear the entire cost of national programs, but there is an essential principle that should be maintained in these matter.”

By contrast, Roosevelt’s first fireside chat started like this:

“My friends, I want to talk for a few minutes with the people of the United States about banking—to talk with the comparatively few who understand the mechanics of banking, but more particularly with the overwhelming majority of you who use banks for the making of deposits and the drawing of checks.”

After Roosevelt’s address, letters poured into the White House in support of the president.

Virginia Miller wrote: “I want to thank you from the bottom of my heart for your splendid explanation of the Bank situation on last evening’s broadcast.”

Viola Hazelberger wrote: “I have regained faith in the banks due to your earnest beliefs.”

And James A. Green said: “You have a marvelous radio voice, distinct and clear. It almost seemed the other night, sitting in my easy chair in the library, that you were across the room from me.”

Suddenly the president seemed accessible. Whereas Herbert Hoover had averaged about 5,000 letters a week, the number of people writing to Roosevelt leapt to 50,000.

It’s no wonder, then, that Trout announced to Americans: “the president wants to come into your home and sit at your fireside for a little fireside chat.” The title stuck. It did feel, to many people, as if the president was sitting in their parlor.

Roosevelt came at the right time. The radio age had just begun, and it only grew during his twelve years in office. About forty percent of Americans had a radio at the beginning of FDR’s term—five years in, almost ninety percent of Americans had a radio.

Certainly it was one thing to have a radio and a large audience, but quite another to speak with the eloquence and clarity that FDR used while speaking to the country (just ask Herbert Hoover). Roosevelt succeeded in reaching a great number of Americans, and giving a boost to their confidence.

Other presidents have similarly used new technologies to communicate with a mass audience. An obvious example is President Trump’s use of Twitter. President Obama used Facebook, and even appeared on “Between Two Ferns” to promote his health care legislation. President Kennedy, too, used the new power of television to reach more Americans. Kennedy gave the first live televised press conference.

Eight-six years ago in 1933, Roosevelt ended his address like this:

“After all, there is an element in the readjustment of our financial system more important than currency, more important than gold, and that is the confidence of the people. Confidence and courage are the essentials of success in carrying out our plan. You people must have faith; you must not be stampeded by rumors or guesses. Let us unite in banishing fear. We have provided the machinery to restore our financial system; it is up to you to support and make it work.

It is your problem no less than it is mine. Together we cannot fail.”

On this day in 1987, Ronald Reagan famously called on Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down this wall”–a wall which physically separated East and West Berlin, and symbolized the separation between the Soviet Block and the West.

On this day in 1987, Ronald Reagan famously called on Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down this wall”–a wall which physically separated East and West Berlin, and symbolized the separation between the Soviet Block and the West. Odyssey of George H.W. Bush, was more focused on what could go wrong rather than the symbolic triumph of the West over the Soviets, which led to a contentious exchange between the president and CBS reporter Lesley Stahl.

Odyssey of George H.W. Bush, was more focused on what could go wrong rather than the symbolic triumph of the West over the Soviets, which led to a contentious exchange between the president and CBS reporter Lesley Stahl.

Dr. Robert Moton, a civil rights activist, gave the keynote address. Although he

Dr. Robert Moton, a civil rights activist, gave the keynote address. Although he

Schoumatoff was standing at her easel painting the president when something in his demeanor changed. She later recalled: “He looked at me, his forehead furrowed in pain, and tried to smile. He put his left hand up to the back of his head and said, ‘I have a terrible pain in the back of my head.’ And then he collapsed.”

Schoumatoff was standing at her easel painting the president when something in his demeanor changed. She later recalled: “He looked at me, his forehead furrowed in pain, and tried to smile. He put his left hand up to the back of his head and said, ‘I have a terrible pain in the back of my head.’ And then he collapsed.” in his own right. Although his approval rating hovered in the

in his own right. Although his approval rating hovered in the