The youngest candidate running for president in 2020 is 37. The oldest is 77. Whether or not voters will make age an issue has yet to be seen, so how has it played out in past presidential campaigns?

By Kaleena Fraga

(to listen to this piece in podcast form click here)

The candidates running for president in 2020 are incredibly diverse. There are men and women, white and black candidates, and candidates with different sexual orientations. There is also a diversity when it comes to age. On the younger side of the spectrum are Beto O’Rourke and Pete Buttigieg (46 and 37, respectively). On the other side there is Bernie Sanders, who is 77, and, if he were to run, Joe Biden, who is 76.

So what role has age played in past presidential campaigns?

It’s certainly come up in the past. The two most famous examples of candidates who wrestled with the “age question” were John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan.

John F. Kennedy

Kennedy, when he ran for president in 1960, was 43 years old. Although his opponent, Richard Nixon, was just four years older, Kennedy faced a barrage of criticism and doubt when it came to the question of his youth. (Of course, by 1960 Richard Nixon had been vice president for eight years, in addition to his service in the House and the Senate, experience which Kennedy shared).

Criticism came from both sides of the aisle. Harry Truman, the last Democratic president, spoke out against Kennedy, saying:

“I am deeply concerned and troubled about the situation we are up against in the world now…That is why I hope someone with the greatest possible maturity and experience would be available at this time. May I urge you to be patient?”

Once Kennedy became the nominee, Truman changed his tune—sort of. He wrote to a former aide:

“[We] are stuck with the necessity of taking the worst of two evils or none at all. So–I’m taking the immature Democrat as the best of the two. Nixon is impossible. So, there we are.”

Experience was definitely a question in the election. Nixon ran ads stressing his 7 1/2 years experience in the White House as Eisenhower’s vice president. The ad ended with a line touting the experience of Nixon and his running mate, Henry Cabot Lodge: “They understand what peace demands” implying, of course, that Kennedy (with his youth and inexperience) did not.

The Democrats fought back. When Eisenhower infamously stated during a press conference that he’d need a week to think of an important contribution or decision made by his vice president, Democrats turned the fumble into an attack ad against Nixon.

Kennedy, for his part, turned his youth into an asset. When he accepted the nomination Kennedy said:

“The Republican nominee-to-be, of course, is also a young man. But his approach is as old as McKinley. His party is the party of the past. His speeches are generalities from Poor Richard’s Almanac. Their platform, made up of left-over Democratic planks, has the courage of our old convictions. Their pledge is a pledge to the status quo–and today there can be no status quo.”

The country, Kennedy said, needed young blood, new ideas, a fresh start. Using rhetoric that will be familiar to anyone who has lived through an American election, Kennedy pressed for change after eight years of Republican power.

It worked—but barely. The election of 1960 was one of the closest in American history.

Ronald Reagan

Reagan, like Kennedy, faced criticism concerning his age, but it came from the other direction. As he prepared to run for reelection, many wondered if the president had grown too old to serve his duties. At 73, he would be the oldest president ever sworn in.

Age had been a question for Reagan ever since he ran for president in 1980. In a debate that year with his future vice president, George H.W. Bush, the moderator asked Bush if he thought Reagan, then 69, was too old to hold office.

“No, I don’t,” said Bush.

“I agree with George Bush,” said Reagan.

Four years later, the question arose again, amplified, this time, by Reagan’s poor performance in the first debate against Walter Mondale. The New York Times wrote that “Mr. Reagan appears less confident than he customarily does on television.”

Reagan hit back against criticism over his performance, and against the line of questioning that he’d lost stamina in the last four years. “I wasn’t tired,” Reagan told the Times. “And with regard to the age issue and everything, if I had as much makeup on as he did, I’d have looked younger, too.”

But Reagan knew he’d had a bad night. As soon as Reagan walked off the debate stage that night he told an aide that he “had flopped.” Mondale, for his part, told an aide, “that guy is gone.” After the debate, Reagan dropped seven points in the polls. Fifty-four percent of Americans gave the debate victory to Mondale; just thirty-four percent thought Reagan had won.

So it was crucial for Reagan to perform well in the 2nd debate. Not only that, he needed to definitively put the “age” question to rest.

He got his chance.

“Mr. President,” said the moderator. “I want to raise an issue that has been lurking out there for two or three weeks…you are already the oldest president in history. And some of your staff say you were tired after your most recent encounter with Mr. Mondale. I recall yet that President Kennedy had to go for days with very little sleep during the Cuban missile crisis. Is there any doubt in your mind that you would be able to function in such circumstances?”

Reagan responded: “Not at all…I want you to know that also I will not make age an issue of this campaign. I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent’s youth and inexperience.”

Even Mondale laughed (although he must have sensed, then, the power of Reagan’s line). It quickly became one of the most iconic of American presidential debates. Lost is what Reagan said next: “I might add that it was Seneca, or it was Cicero, I don’t know which, that said, ‘If it was not for the elders correcting the mistakes of the young, there would be no state.'”

Reagan won the election in a landslide. Although he would not be officially diagnosed with Alzheimers until 1994, speculation was rife that he suffered from the disease while in office. During the Iran-Contra affair, much of Reagan’s defense rested on the fact that he could not remember certain facts.

***

So how will age play out in 2020? Sanders, who would be 79 on inauguration day were he to win, acknowledged but dismissed the age issue. “I would ask people to look at the totality of who I am,” Sanders said, “[age is] part of a discussion, but it has to be part of an overall view of what somebody is and what somebody has accomplished.”

Although Joe Biden has not yet officially announced his own candidacy (he would be 78 on January 20th 2021) he and his team are reportedly considering measures that would help allay the question. Among them: choosing a running mate early (Stacey Abrams is rumored) and promising to serve only one term.

Pete Buttigieg, who is enjoying a bump in the polls, frames his youth (Buttigieg is 37) as an asset. “We’re the generation with the most at stake,” Buttigieg said, referencing climate change and the increasing issue of economic disparity. “[We] were out there in Afghanistan and Iraq, and I think we’ve earned place in this conversation.”

Age will definitely be a question on the Democratic side—and certainly it will come up as the election progresses. Donald Trump, after all, is 72.

President Barack Obama

President Barack Obama

of political leadership.” Eight years

of political leadership.” Eight years

On this day in 1987, Ronald Reagan famously called on Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down this wall”–a wall which physically separated East and West Berlin, and symbolized the separation between the Soviet Block and the West.

On this day in 1987, Ronald Reagan famously called on Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down this wall”–a wall which physically separated East and West Berlin, and symbolized the separation between the Soviet Block and the West. Odyssey of George H.W. Bush, was more focused on what could go wrong rather than the symbolic triumph of the West over the Soviets, which led to a contentious exchange between the president and CBS reporter Lesley Stahl.

Odyssey of George H.W. Bush, was more focused on what could go wrong rather than the symbolic triumph of the West over the Soviets, which led to a contentious exchange between the president and CBS reporter Lesley Stahl.

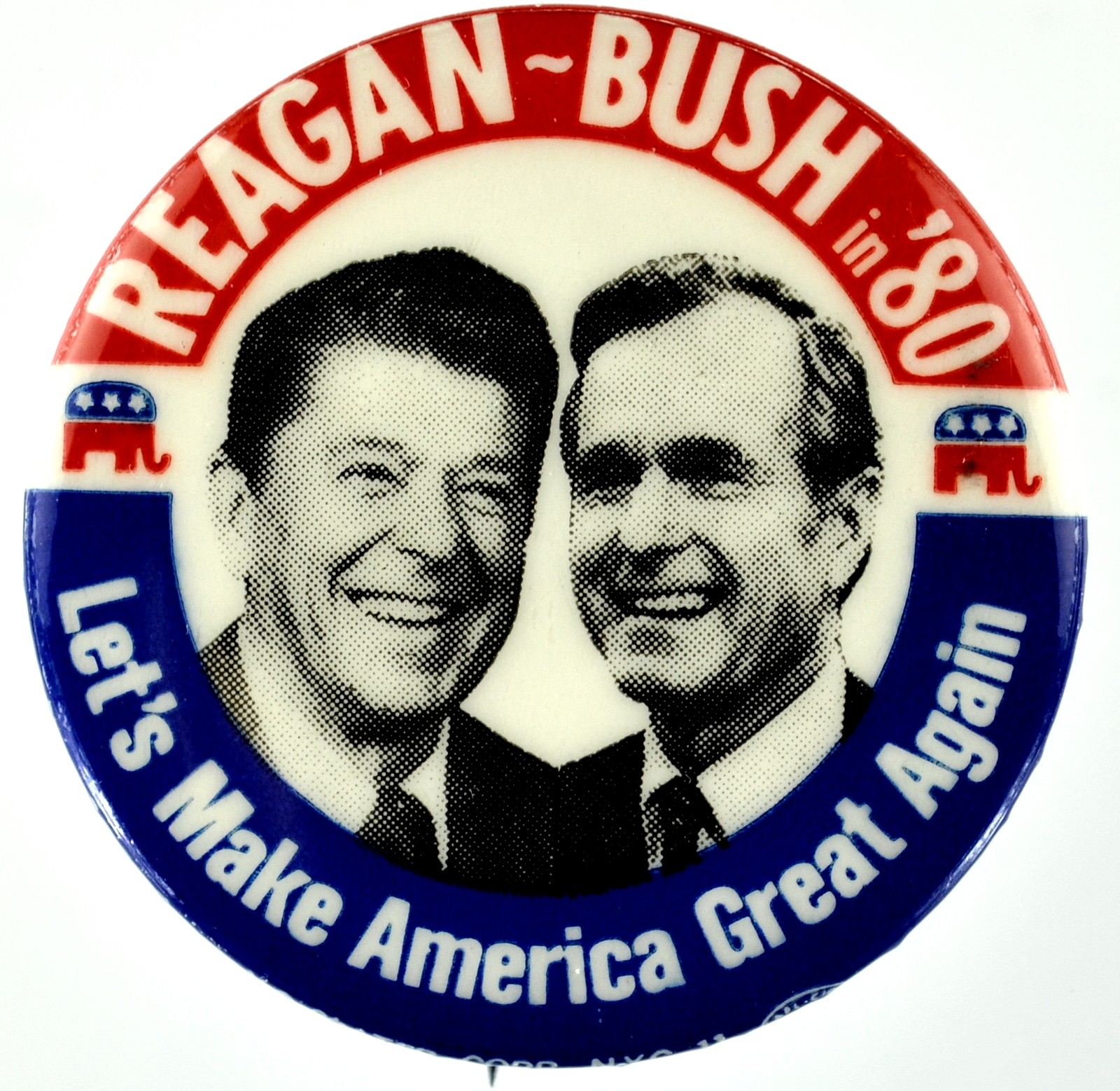

4. Reagan-Bush ran a slogan in 1980 that will sound familiar to many Americans today: “Let’s Make America Great Again.”

4. Reagan-Bush ran a slogan in 1980 that will sound familiar to many Americans today: “Let’s Make America Great Again.” enthusiastic. The New York Times called the run up to the endorsement “one of Washington’s longest-running and least suspenseful political dramas,” after Reagan insisted on waiting for the end of the Republican primary to announce his pick. Despite his nickname as the “Great Communicator” and Bush’s eight years of service as VP, Reagan flubbed Bush’s name during the endorsement, pronouncing it George Bosh.

enthusiastic. The New York Times called the run up to the endorsement “one of Washington’s longest-running and least suspenseful political dramas,” after Reagan insisted on waiting for the end of the Republican primary to announce his pick. Despite his nickname as the “Great Communicator” and Bush’s eight years of service as VP, Reagan flubbed Bush’s name during the endorsement, pronouncing it George Bosh.

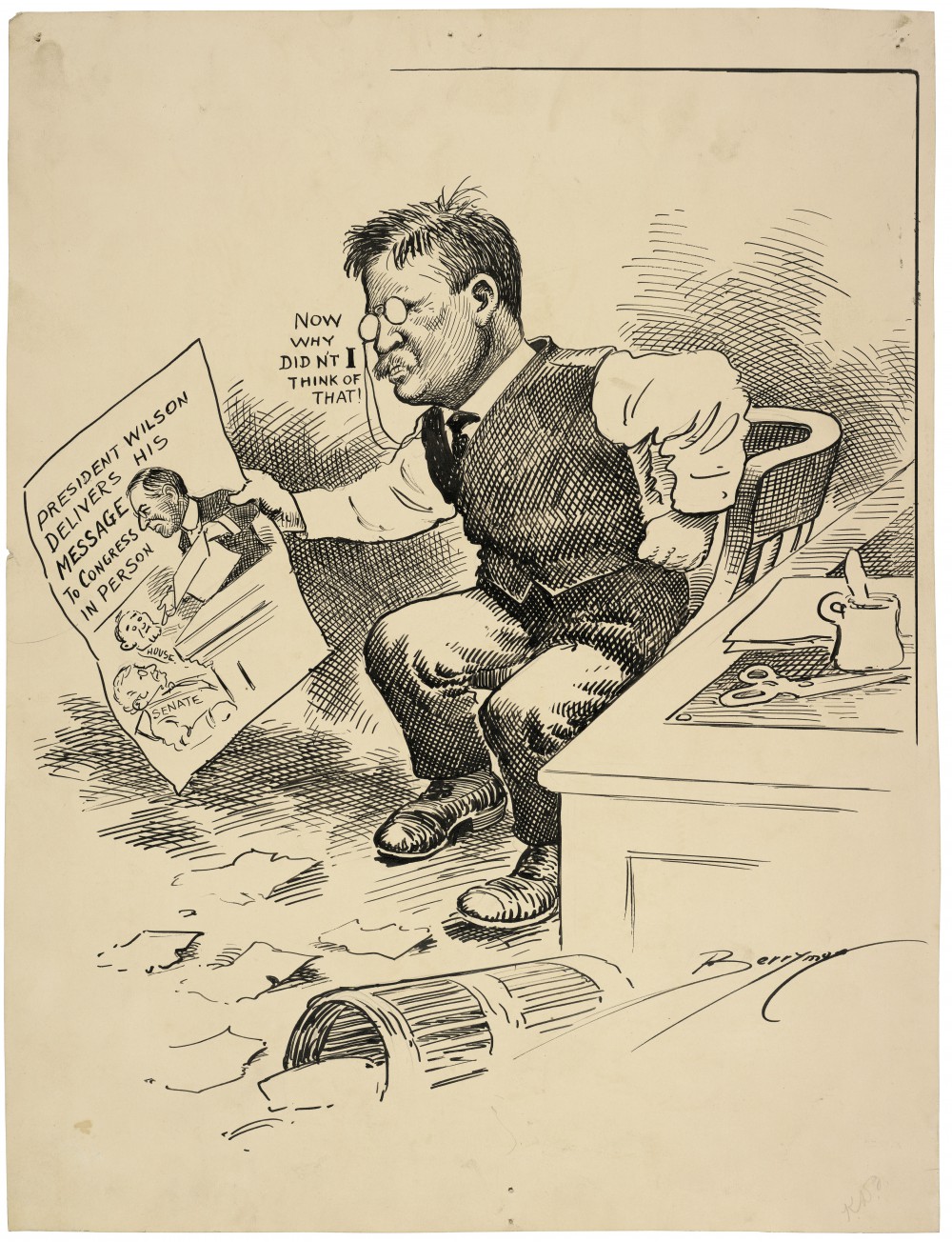

twenty-eight minutes. Each of his addresses to Congress were around or above the one hour mark. His speech was also the longest at 9,190 words (Washington’s, by comparison, was the shortest at 1,089 words).

twenty-eight minutes. Each of his addresses to Congress were around or above the one hour mark. His speech was also the longest at 9,190 words (Washington’s, by comparison, was the shortest at 1,089 words).