By Kaleena Fraga

President Trump is in Europe this week, stirring up animosity among European allies as he rages on Twitter about their contributions to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Trump has taken a decidedly different approach to NATO than his predecessors, and many European leaders seem to be at a loss when it comes to dealing with the new American policy. The European Council president, Donald Tusk, even went as far as to say, “Dear America, appreciate your allies, after all you don’t have that many.”

For many Americans of a certain generation, NATO has always existed. So where did it come from? To answer this, we must look to Harry Truman.

Following WWII, many European and American leaders were alarmed by Soviet aggression. This led to several alliances and pacts among European countries, seeking to combine Western European defenses with the United States’ policy of containment. NATO, then, was born in part from Harry Truman’s “Truman Doctrine” which pledged support to nations threatened by communism and sought to counter Soviet expansion.

The twelve original countries (the United States, Canada, Belgium, Denmark, France, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, and Great Britain) signed an agreement that stated “an armed attack against one or more of them…shall be considered an attack against them all.” President Truman called NATO “a shield against  aggression.”

aggression.”

NATO wasn’t a universally accepted idea in the United States. Just as isolationists had opposed President Wilson’s League of Nations, they rejected the idea of involving the United States in a multinational alliance. This push was led by Robert Taft, the son of the former president William Howard Taft, who said that NATO “was not a peace program, but a war program.” The Soviet Union felt threaten by the alliance, and created the Warsaw Pact in 1955 as their own version of NATO.

After a lengthy confirmation process in the Senate, the NATO treaty was confirmed.

When Harry Truman signed the treaty on August 24, 1949 he declared:

“By this treaty, we are not only seeking to establish freedom from aggression and from the use of force in the North Atlantic community, but we are also actively striving to promote and preserve peace throughout the world.”

Since it’s founding, NATO has fought ISIS and helped to broker peace in Bosnia. After the two world wars of the 20th century, it has maintained relative peace among European nations. In the aftermath of 9/11, NATO invoked Article 5 for the first and only time–this being the clause that declares that an attack on one nation is an attack on them all–in order to deliver assistance to the United States.

The world is very different than the 1940s and 1950s when NATO was born. And so is the man in the White House. Whether or not Trump continues to engage with NATO or removes the United States from the alliance all together has yet to be seen.

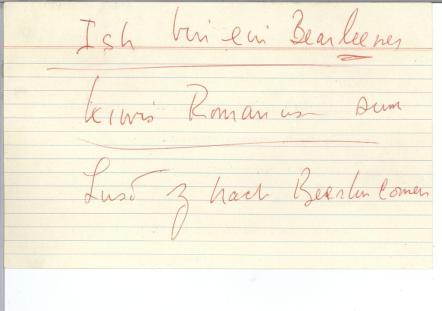

On this day in 1987, Ronald Reagan famously called on Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down this wall”–a wall which physically separated East and West Berlin, and symbolized the separation between the Soviet Block and the West.

On this day in 1987, Ronald Reagan famously called on Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down this wall”–a wall which physically separated East and West Berlin, and symbolized the separation between the Soviet Block and the West. Odyssey of George H.W. Bush, was more focused on what could go wrong rather than the symbolic triumph of the West over the Soviets, which led to a contentious exchange between the president and CBS reporter Lesley Stahl.

Odyssey of George H.W. Bush, was more focused on what could go wrong rather than the symbolic triumph of the West over the Soviets, which led to a contentious exchange between the president and CBS reporter Lesley Stahl.