By Kaleena Fraga

On this day in 1963, John F. Kennedy addressed an exultant crowd of 1.1 million Germans–about 58% of Berlin’s population. During this speech, Kennedy would famously declare:

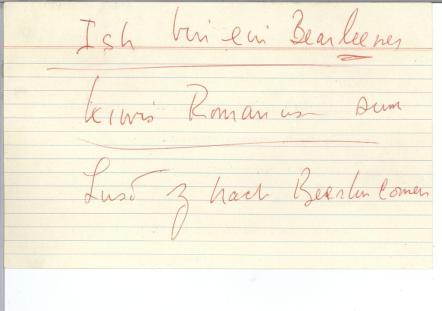

“Two thousand years ago, the proudest boast was ‘Civis Romanus sum. Today, in the world of freedom, the proudest boast is ‘Ich bin ein Berliner!’ ”

These were words that he’d jotted down himself, moments before taking the stage. They actually weren’t in his prepared text at all.

The crafting of the speech was an exercise in international politics. Kennedy and his team wanted to make a defiant statement on the Soviet’s doorstep–at this point the wall was only two years old–but without upsetting the Soviets too much. The first draft didn’t go far enough, and both Kennedy and the American commandant in Berlin found it “terrible.” Kennedy’s solution was to rewrite the speech by himself.

The famous line Ich bin ein Berliner later turned into a myth that JFK had actually told one million Germans I am a jelly donut, but this is patently false. The crowd gathered in Berlin completely understood the meaning of Kennedy’s statement–and went wild for it. In any case, although a Berliner is a type of donut in Germany, it’s actually called a Pfannkucken in Berlin.

The line was perhaps not original–it appears that the ex-president Herbert Hoover wrote the same line in a guest book in Berlin in 1954, although it’s doubtful Kennedy knew that–but it made a huge impression on both the gathered Germans and the Soviets, watching closely from the other side of the city. The Germans renamed the square where JFK had delivered the speech John F. Kennedy Platz after Kennedy’s assassination. Nikita Krushchev gave a speech of his own in Berlin two days after JFK, to a crowd of roughly 500,000 Germans. His pronouncement I love the wall did not have the same effect as JFK’s Ich bin ein Berliner.

The memory of JFK is still strong in Berlin. The museum The Kennedys hosts the second largest collection of Kennedy memorabilia in the world, and plays JFK’s Berlin speech on a loop. It’s worth watching: