By Kaleena Fraga

On November 3rd, 2020 the United States had an election. By November 7th, it had a winner — and by November 23rd, a loser, when President Trump officially acknowledged the transition to Joe Biden’s presidency.

Now, January 20th, 2021 looms in the distance. What will the transition from Trump to Biden look like on Inauguration Day? If it’s awkward or stiff — or if Trump simply doesn’t show up — it would reflect a long tradition of a “chilly” January day.

Even before Inauguration Day moved to January 20th — it was previously held on March 4th but advances in transportation made assembling the new government easier and faster —presidential transitions were often awkward. John Adams left town before his once friend, now foe, Thomas Jefferson was sworn in in 1801. His son, John Quincy Adams, did the same on the day his rival Andrew Jackson took the oath of office in 1829. When Ulysses S. Grant was inaugurated, he refused to share a carriage with the deeply unpopular Andrew Johnson. During Grant’s inauguration in 1869, Johnson remained in the White House.

Today, we’ll take a look back at a few other awkward presidential transitions in the 20th-century.

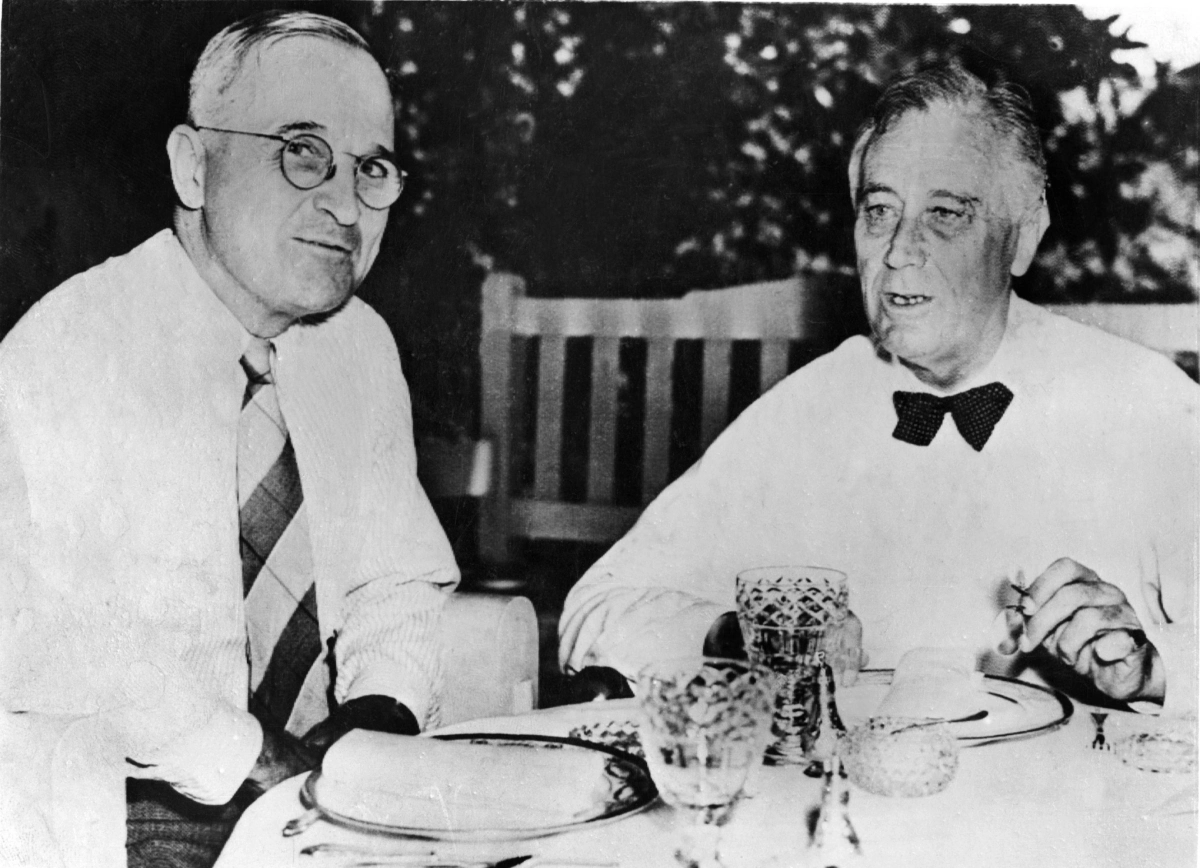

Harry Truman to Dwight D. Eisenhower

When Dwight D. Eisenhower won the 1952 election against Adlai Stevenson, he ended two decades of Democratic rule. And “Ike” had not just won—he swept to victory with 442 electoral votes to Stevenson’s 89.

Harry Truman, the incumbent, had worked with Eisenhower as World War II waned. Since then, their relationship had soured. Truman saw Eisenhower as dangerously anti-communist, especially since Eisenhower had done nothing publicly to denounce the rabble-rousing of Joseph McCarthy. Eisenhower had planned to denounce the firebrand senator in a speech in Wisconsin, but backed out. Truman fumed: “[It was] one of the most shocking things in the history of this country. The trouble with Eisenhower . . . he’s just a coward . . . and he ought to be ashamed for what he did.”

Still, Truman was gracious in defeat. He invited Eisenhower to the White House after the election, but felt that the former general seemed unsuited to the job. Frustrated, Truman wrote that everything he said to Eisenhower “went in one ear and out the other.” Later, Truman mused that Eisenhower’s military background would prove a disadvantage, writing:

“He’ll sit right here and he’ll say do this, do that! And nothing will happen. Poor Ike–it won’t be a bit like the Army. He’ll find it very frustrating.”

The former general, Truman noted coolly, “doesn’t know any more about politics than a pig knows about Sunday.”

Eisenhower also felt frosty. He saw Truman as an inept leader surrounded by cronies. When discussing the upcoming inauguration, he wondered aloud if he could “stand” sitting next to Truman. Eisenhower had a solution for dealing with people he disliked. He wrote their names on index cards and filed them under “To Be Ignored.” The next eight years would prove that Eisenhower meant it—the two presidents had little contact during Eisenhower’s two terms in office. (When Eisenhower was in Missouri and Truman tried to set up a meeting, he was told that the president had no room in his schedule. Reportedly, Truman could not refer to Eisenhower in later years without using profanity.)

Neither man had thawed by Inauguration Day. The clear, simmering hatred between the two was “like a monsoon”, according to White House advisor Clark Clifford. There were petty arguments over what kind of hats to wear—Eisenhower, without alerting Truman, wore a Homburg (similar to a fedora) instead of a silk top hat—and Eisenhower refused to enter the White House before he was sworn in, which meant he declined Truman’s invitation for a pre-inauguration cup of coffee

In fact, Eisenhower refused to even get out of the car. One CBS correspondent called it a “shocking moment.” The White House head usher, J.B. West, said “I was glad I wasn’t in that car.”

But despite the animosity between Eisenhower and Truman, Truman had gone out of his way to make Eisenhower’s inauguration special. Without Eisenhower knowing, Truman had invited the general’s son, John, to temporarily leave his post in Korea to see his father sworn in.

Eisenhower asked Truman who had invited John back. According to Eisenhower, Truman replied, “I did.”

Jimmy Carter to Ronald Reagan

Ronald Reagan won the election in 1980 by setting himself up as the opposite of Jimmy Carter. Instead of “malaise” you had “Morning in America“.

The two men had traded razor-sharp barbs during the campaign. Carter suggested that Reagan was a racist who couldn’t be trusted with the nuclear codes. Reagan quipped, “The conduct of the presidency under Mr. Carter has become a tragic-comedy of errors. In place of competence, he has given us ineptitude.” Reagan claimed the country’s economic recovery couldn’t start until Carter lost his job.

The transition, then, was unsurprisingly tense. When the two men met after the election to discuss national security, Reagan listened without comment and took no notes — much to Carter’s chagrin. During the meeting, Carter noted that being president was different than being governor (a role both men had had). For one thing, CIA briefings started at 7am. Regan smiled and said, “Well, he’s sure going to have to wait a long while for me.” Carter was unamused. Reagan didn’t care. He wanted “nothing to do” with Carter.

Reagan’s family did nothing to thaw tensions. A rumor came out that Nancy Reagan had asked if the Carters could move out out of the White House early—so that she could redecorate. Reagan’s son, Ronald, told the press he wouldn’t shake President Carter’s hand because “[Carter] has the morals of a snake.”

On Inauguration Day, Carter cut a weary figure. He had been up for forty-eight hours attempting to free the American hostages in Iran — who had been held in captivity for 444 days.

As they rode in a limousine together on the morning of Reagan’s inauguration, Carter was quiet, deep in thought about the hostages. Several hours earlier, he’d informed his successor that their release was imminent—indeed, they would be released that day. Reagan filled the silence. Later, Carter called Reagan’s anecdotes “remarkably pointless.” One story involved a former studio executive named Jack Warner and as Carter emerged from the car he muttered to an aide, “Who is Jack Warner?”

During Reagan’s presidency, the two men continued to attack each other. Reagan often invoked Carter to show how bad things used to be. “Remember, we were told it was a malaise, and we just had to get used to doing with less?” Reagan said during his presidency. “Well, the people knew different.” Carter also did not restrain from critiquing Reagan’s performance as president.

Still, when Carter opened his presidential library, he invited his former foe to the dedication ceremony. Reagan agreed—perhaps out of presidential duty. One of his staffers quipped that it would be strange to see the two men together, “kind of like mixing peanuts and jelly beans.”

Bill Clinton to George W. Bush (the Staff)

The transition between Bill Clinton and George W. Bush was fairly civil—especially given the controversy of the 2000 election, which came down to a recount in Florida and a Supreme Court decision.

There were a few instances of awkwardness. When President Clinton invited President-Elect Bush to coffee at the White House, Clinton arrived 10 minutes later. This irritated Bush, who was so punctual that he often locked doors once a meeting had begun. What’s more, Clinton also invited his vice president—Bush’s campaign rival, Al Gore.

But the real tension came from Clinton’s White House staff. Angered by remarks by Bush during the campaign—especially his insistence that he would restore honor and integrity to the Oval Office—they did their best to make life difficult for their replacements.

The Washington Post reported that departing Clinton staffers left quite a welcome for the Bush people, including scattered bumper stickers, obscene voicemail greetings, damaged furniture, dismantled keyboards (some people removed the “W” from their keyboards), vaseline smeared on desks, unplugged refrigerators, writing on the wall, missing TV remotes, telephones and drawers glued shut, and locks smashed.

One Bush staff member described the office space as “filthy” and one room contained a “malodorous stench.” The Clinton people left behind “unopened beer and wine bottles, a blanket, shoes, and a T-shirt with a picture of a tongue sticking out on it draped over a chair.“

One Clinton staffer admitted gleefully to what they had done, telling the Government Accountability Office (GAO) that he had: “left a voicemail greeting on his telephone indicating that he would be out of the office for the next four years due to a decision by the Supreme Court.”

The prank cost the government somewhere between $13,000 and $14,000 to fix.

—

The campaign of 2020 was certainly a bitter one—even to the end. So, it’ll be interesting to see how President Trump leaves and how President Biden arrives. Will it be as frosty as Eisenhower and Truman? Or will Mr. Trump take a page out of the Adams’ book, and skip town before the celebrations begin?

aggression.”

aggression.”

United States would “take whatever steps were necessary” to stop the communists. He added that he never wanted to use the bomb again, acknowledging, “it is a terrible weapon, and it should not be used on innocent men, women and children.”

United States would “take whatever steps were necessary” to stop the communists. He added that he never wanted to use the bomb again, acknowledging, “it is a terrible weapon, and it should not be used on innocent men, women and children.” In 1952, Korea was a

In 1952, Korea was a

front page to her decision to not bow to the Queen. The Guardian

front page to her decision to not bow to the Queen. The Guardian

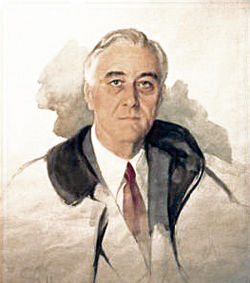

Schoumatoff was standing at her easel painting the president when something in his demeanor changed. She later recalled: “He looked at me, his forehead furrowed in pain, and tried to smile. He put his left hand up to the back of his head and said, ‘I have a terrible pain in the back of my head.’ And then he collapsed.”

Schoumatoff was standing at her easel painting the president when something in his demeanor changed. She later recalled: “He looked at me, his forehead furrowed in pain, and tried to smile. He put his left hand up to the back of his head and said, ‘I have a terrible pain in the back of my head.’ And then he collapsed.” in his own right. Although his approval rating hovered in the

in his own right. Although his approval rating hovered in the