By Kaleena Fraga

If elected president, Cory Booker would join a small club of men who held the presidency without a wife

(to listen to the piece in podcast form click here)

During a radio interview on February 5th about his 2020 White House run, New Jersey Senator Cory Booker acknowledged that he has a girlfriend. Still, Booker has endured speculation (much as Lindsey Graham did) about what his presidency would look like if he entered the White House as a single man.

It’s rare in American history, but not unheard of. The single men of the White House fall into a couple of narrow categories. They were widowers; men whose wives died during their presidencies; single or widowed men who married during their presidency; or presidents who never married at all.

Widowers

Thomas Jefferson’s wife died almost twenty years before his presidency. Although the role of first lady was not strongly defined, various women close to Jefferson resided over social functions at the White House. These included his daughter, Patsy, and the wife of his best friend, Dolley Madison. Dolley Madison played an important role building relationships with the powerful in Washington D.C.–especially since Jefferson and her husband much preferred books to people.

Andrew Jackson’s case was a bit different. He and his wife, Rachel, had endured vicious attacks during the campaign over their marriage (Rachel had been married to another man when she met Jackson, and there was some overlap between her first and second marriages). She died shortly after his election in 1828. Although she’d always suffered health problems, Jackson blamed his political enemies and their attacks for exacerbating her illness and causing her death.

“My mind is so disturbed,” Jackson wrote to a friend, shortly after his election and Rachel’s death, “that I scarcly [sic] write, in short my dear my heart is nearly broke.”

Martin Van Buren, like Jefferson, entered the White House as a widower. His wife similarly died almost two decades before his presidency, and Van Buren never remarried.

Chester A. Arthur’s wife, Nell, died about a year before Arthur entered the White House–although he initially did so as James Garfield’s vice president in 1881. Arthur, who ascended to the presidency after the assassination of Garfield, never remarried.

Tragedy at the White House

John Tyler, Benjamin Harrison, and Woodrow Wilson all lost their wives during their administrations.

White House Weddings

There’s an overlap between the last category and this one. John Tyler and Woodrow Wilson remarried during their presidencies. (Harrison also remarried, but not until after his presidency).

Grover Cleveland entered the White House as a bachelor in 1884. He also arrived on a wave of controversy surrounding the paternity of a child born of wedlock.

Cleveland, at 49, would eventually marry the daughter of his former law partner, Frances Folsom. Folsom had known Cleveland since she was 12. At 21, she would become the youngest first lady in American history.

Bachelor for Life

James Buchanan, while regarded as one of the nation’s worst presidents, is perhaps best known as the nation’s only bachelor president. Buchanan never wed, and presided over the White House alone. Today, there is speculation that Buchanan may have been America’s first gay president.

Buchanan’s bachelorhood did not go unnoticed by the American public (and certainly not by his opposition). One campaign ditty went:

“Whoever heard in all of his life,

Of a President without a wife?”

Andrew Jackson once sneered that Buchanan, and his close friend Rufus William King, who died before Buchanan’s presidency, were “Miss Nancy” and “Aunt Fancy.”

There’s no definitive proof that Buchanan was gay–especially since male friendships of the era were largely more intimate than today. Still–the two men shared a fifteen year friendship, a room in a Washington boardinghouse as congressmen, and letters, which their respective nieces burned.

***

As for Booker? After admitting he had “someone special” in his life, the exchange went on:

“Oh, so Cory Booker’s got a boo?”

“I got a boo,” Booker responded.

Will Cory Booker’s boo follow him to the White House, should the 2020 race lead him there? Perhaps. But if Booker does arrive at the White House, and if he arrives solo, he certainly won’t be the first to preside over the presidency alone.

Barbara Bush met her husband at sixteen and married him four years later, after his brush with death during WWII. Before marriage Mrs. Bush had enrolled in Smith College–she was a voracious reader as a girl–and helped out in the war effort by

Barbara Bush met her husband at sixteen and married him four years later, after his brush with death during WWII. Before marriage Mrs. Bush had enrolled in Smith College–she was a voracious reader as a girl–and helped out in the war effort by  own political views, she was more outspoken before and after H.W.’s term in office. During his vice presidential run she

own political views, she was more outspoken before and after H.W.’s term in office. During his vice presidential run she

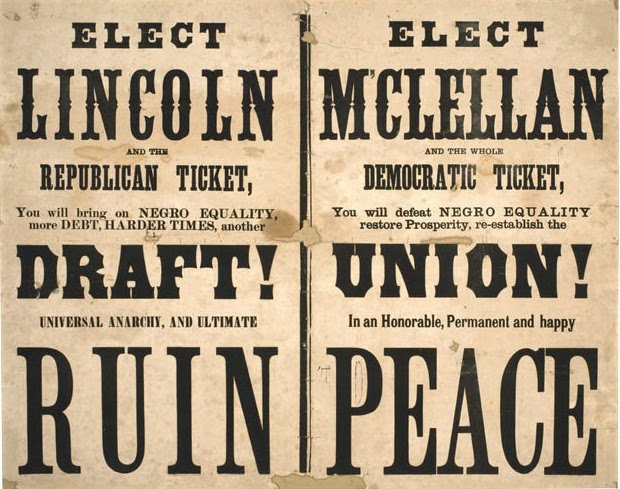

Racial violence perpetrated both sides of the conflict. That year, the Democratic Party ran a racist, anti-war campaign, warning that emancipation meant black people would move North in droves and force whites out of their homes. “The Constitution as it is, the Union as it was, and the negroes where they are,” was their campaign slogan. Democrats gained 34 seats in the House of Representatives, won gubernatorial races in New York and New Jersey, and won control of several state legislatures. In 1863, Horatio Seymour, the Democratic governor of New York, said, “I assure you I am your friend,” to anti-draft rioters who had lynched black doormen and burned down the Colored Orphan Asylum in New York City.

Racial violence perpetrated both sides of the conflict. That year, the Democratic Party ran a racist, anti-war campaign, warning that emancipation meant black people would move North in droves and force whites out of their homes. “The Constitution as it is, the Union as it was, and the negroes where they are,” was their campaign slogan. Democrats gained 34 seats in the House of Representatives, won gubernatorial races in New York and New Jersey, and won control of several state legislatures. In 1863, Horatio Seymour, the Democratic governor of New York, said, “I assure you I am your friend,” to anti-draft rioters who had lynched black doormen and burned down the Colored Orphan Asylum in New York City.  letter to Lincoln, “I have given the subject of arming the negro my hearty support. This, with the emancipation of the negro, is the heavyest blow yet given to the Confederacy … by arming the negro we have added a powerful ally. They will make good soldiers and taking them from the enemy weakens him in the same proportion they strengthen us. I am therefore most decidedly in favor of pushing this policy to the enlistment of a force sufficient to hold all the South falling into our hands and to aid in capturing more.”

letter to Lincoln, “I have given the subject of arming the negro my hearty support. This, with the emancipation of the negro, is the heavyest blow yet given to the Confederacy … by arming the negro we have added a powerful ally. They will make good soldiers and taking them from the enemy weakens him in the same proportion they strengthen us. I am therefore most decidedly in favor of pushing this policy to the enlistment of a force sufficient to hold all the South falling into our hands and to aid in capturing more.” Lincoln’s second inauguration happened on March 4, 1865, when Union victory was imminent. He closed his Second Inaugural Address by extending an olive branch to the defeated Confederates and looking ahead to Reconstruction: “With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and lasting peace among ourselves, and with all nations.”

Lincoln’s second inauguration happened on March 4, 1865, when Union victory was imminent. He closed his Second Inaugural Address by extending an olive branch to the defeated Confederates and looking ahead to Reconstruction: “With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and lasting peace among ourselves, and with all nations.”