Hmmm…I wonder why this subject has come to mind. In any case, presidents have a tendency to hide their health concerns from the American public. We take a look at two examples of American presidents who hid health scares.

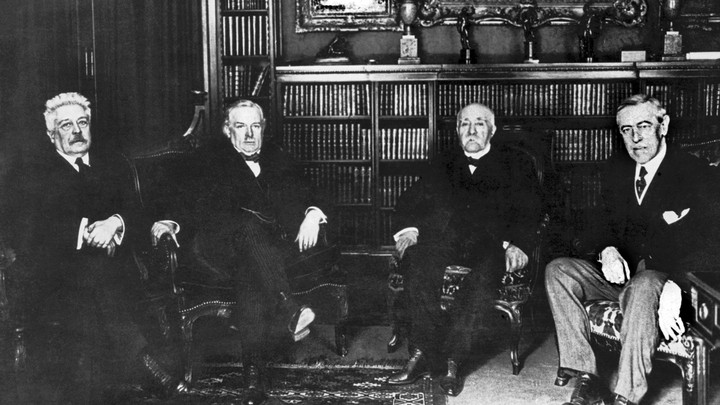

Woodrow Wilson’s Stroke (1919)

One of the most striking moments of obfuscation from the White House belongs to Woodrow Wilson. In 1919, the president suffered a devastating stroke.

On September 3rd, the president had embarked on a country-wide train trip. He wanted to convince his fellow Americans to support the League of Nations. During the trip, Wilson’s health suffered. He lost his appetite and his asthma began to bother him.

On September 25th, Wilson took a turn for the worse. His wife, Edith, noticed that her husband’s facial muscles were twitching and Wilson complained of nausea and a splitting headache. On September 26th, Wilson’s speaking tour was canceled. On October 2nd, back at the White House, the president suffered a devastating stroke that left him partially paralyzed.

Although news of the president’s stroke began to come out in February 1920, most Americans did not realize its severity. They didn’t realize that—as Wilson struggled to recover—his wife had taken over as de facto president. After all, this was decades before the 25th amendment would put a process in place for what to do when the president is incapacitated.

Edith Wilson, who described her role as a “stewardship” denied that she made any decisions on her own. But she admitted that she decided “what was important and what was not, and the very important decision of when to present matters to my husband.”

Grover Cleveland’s Jaw Surgery (1893)

Grover Cleveland, who holds the amusing honor of being the only American president to serve two, non-consecutive terms, also hid his health problems from the nation.

Shortly after his inauguration—his second, that is, in 1893, eight years after his first—Cleveland noticed a strange rough spot on the roof of his mouth. A few months later it had grown in size and his doctor confirmed what Cleveland feared. The president had cancer. “It’s a bad looking tenant,” Cleveland’s doctor told him. “I would have it evicted immediately.”

Cleveland knew he would have to hide his condition from the public. In 1893, a considerable stigma existed around cancer, called the “dread disease.” In addition, Cleveland feared that revealing his illness would send the already suffering economy into a tailspin.

The solution? Cleveland told the public that he was going on a fishing trip. And although the president would spend a few days on a yacht, he would not be doing any fishing. Doctors had been summoned to remove the cancer from his mouth.

During the 90-minute surgery, a team of six surgeons aboard a moving vessel extracted the tumor, five of Cleveland’s teeth, and a section of the president’s left jawbone. They did this through the roof of the president’s mouth—which left no marks to alert the public. Indeed, keeping Cleveland’s famous moustache intact was a stipulation of the surgery.

The American public was kept entirely in the dark. When an astute journalist named E.J. Edwards published the truth of the matter in the Philadelphia Press, the president and his team firmly denied it. The public turned against Edwards, labeling his story a “deliberate falsification.”

Edwards’ reputation was in tatters—but, twenty-four years later, he would be redeemed. In 1917, one of the surgeons from the boat acknowledged that Edwards had been right, noting that the journalist had been, “substantially correct, even in most of the details.”

By then, however, Cleveland had left office and died of a heart attack.

—

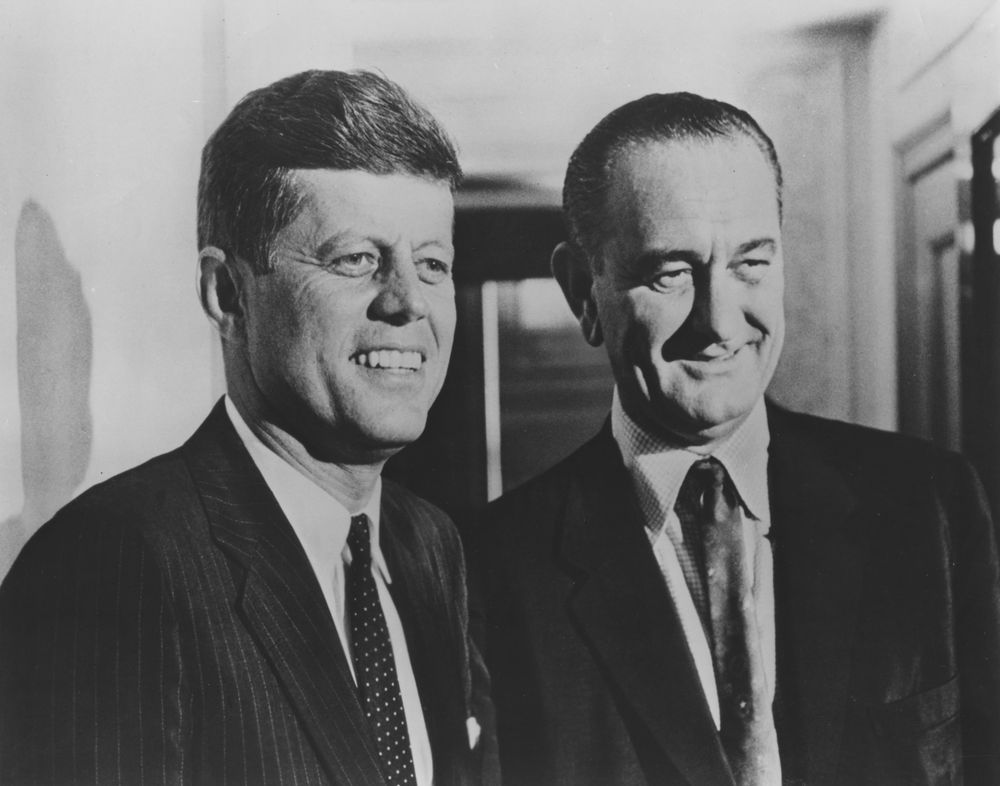

Other examples of American presidents hiding their illnesses abound throughout the country’s history. John F. Kennedy struggled with Addison’s disease and back issues. Some close to Ronald Reagan—including his own son—claim that the president suffered from Alzheimer’s while in office, although the majority of those close to Reagan deny this.

Franklin Roosevelt also presents an interesting case. Despite a persistent belief that he hid his polio from the public, the president’s condition was not a secret—newspapers had published articles that included information about his wheelchair and leg braces. The president’s disability was discussed often.

However, Roosevelt believed it was important that Americans did not see him in a wheelchair. He wanted Americans to believe that he was capable. That’s why he would stand to give a speech, even at great cost to himself. (If you look at photos of Roosevelt speaking while standing, you may notice how tightly he grips the edges of the podium.)

Roosevelt also asked the press to avoid taking photographs of him walking or being transferred into a car. They didn’t always follow the rules. But if someone did snap a photograph of Roosevelt that the president didn’t like, the Secret Service leapt into action.

In 1936, Editor & Publisher reported just how the Secret Service would react to an aggressive photographer—by taking the camera and tearing out the film. In 1946, the White House photography corps backed this up. They acknowledged that if they took the kind of photographs that the president had asked them to avoid, they would have “their cameras emptied, their films exposed to sunlight, or their plates smashed.”

In any case, hiding health scares seems to be a strong tradition among American presidents. It makes sense. It’s easy to draw a line between the health of the nation and the health of its executive.