By Duane Soubirous

The U.S. Constitution outlines the structure of democratic government while limiting the powers of an elected majority; the First Amendment famously guarantees the freedoms of religion, speech, press, peaceful assembly, and petition of grievances. The Constitution also guaranteed the right to own slaves, without actually using the word ‘slave,’ until the Thirteenth Amendment’s ratification, eight months after President Lincoln’s assassination.

Abraham Lincoln believed that slavery was a states’ rights issue and any national attempt to end it would be futile, but he knew that the national government could take the first step in ending slavery by stopping its growth. Lincoln argued that slavery, a “moral, social and political evil,” must be respected where it was already established, but denied from expanding into new territories. This stance on slavery might seem weak today, but in 1860, it was too extreme for South Carolina.

The election of Abraham Lincoln so enraged South Carolinians that they seceded three months before he was even inaugurated. By Feb. 1, one month before inauguration, the rest of the Deep South—Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas—had followed suit. Virginia seceded after Confederates bombarded Fort Sumter in April, followed by Arkansas, North Carolina and Tennessee. Every seceded state was a slave state, but not all slave states seceded.

In order to keep the Border States—Missouri, Kentucky, West Virginia (which had seceded from Confederate Virginia and became the 35th state to enter the Union), Maryland and Delaware—in the Union, Lincoln assured those states that the Civil War wasn’t about ending slavery, it was about upholding the presidential oath to “preserve, protect and defend” the Constitution. Lincoln (unsuccessfully) hoped his conciliatory approach would also foster Union sentiment in the South and encourage loyal Southerners to vote Confederates out of office.

John C. Frémont, the Mexican-American War general nicknamed “the Pathfinder” who became the first presidential nominee of the Republican Party in 1856, commanded the Union army in Missouri. On Aug. 30, 1861, Frémont issued a proclamation freeing all slaves under his control. Northerners exalted Frémont as the emancipator they wished Lincoln was, but Kentucky and Maryland threatened to secede. Lincoln ordered Frémont to rescind his proclamation, a move that Frederick Douglass denounced as weak, imbecile, and absurd. In May 1862, General David Hunter similarly declared all slaves free in his Department of the South, and Lincoln again ordered a general to rescind an emancipation proclamation.

While Lincoln quarreled with his generals, Republicans took advantage of their post-secession lopsided majority in Congress and passed laws restricting slavery. By July 1862, Congress declared that Confederate slaves who escaped to Union lines would be forever free, emancipated slaves in the District of Columbia and abolished slavery in the territories (Congress ignored the Dred Scott decision ruling that they couldn’t abolish slavery in the territories). Lincoln supported a more gradual approach to emancipating D.C. slaves and worried the bill would outrage Maryland, but he signed it into law anyways.

As the Civil War dragged on and Confederates used their slaves against the Union army, Lincoln saw emancipation as a military necessity. Slaveowners long asserted that the right to own slaves was protected by the Fifth Amendment, which states no person shall “be deprived of life, liberty and property,” but the Constitution allowed Lincoln, as commander-in-chief in a time of war, to seize Confederates’ property.

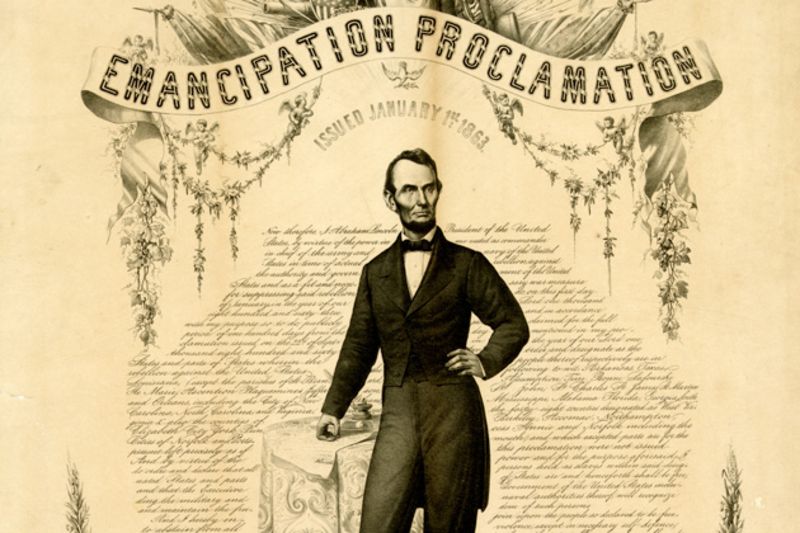

After the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam, Robert E. Lee’s first invasion of the North, Lincoln proclaimed that effective January 1, 1863, all slaves located within areas controlled by the Confederacy “shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” Not only did the Emancipation Proclamation exclude the Border States that remained loyal, it also excluded Tennessee and specific counties in Louisiana and Virginia, which had been pacified by the Union Army. Abolitionists decried the Emancipation Proclamation’s legalese and emphasis of military necessity over justice and morals, but Abraham Lincoln wrote the emancipation to convey its constitutionality to proslavery Democrats, Border States, and the Supreme Court (still led by Roger Taney of the Dred Scott decision).

It’s impossible to know how long slavery would have continued had the South not seceded, but prior to 1861 Abraham Lincoln would have considered his presidency a success if he could “rest in the belief that [slavery] is in the course of ultimate extinction.” By refusing to acquiesce to a majority that desired slavery to stay where it was and not expand, South Carolina put in motion the events that led to its sudden eradication. Declaring slaves free was one thing, however; Lincoln needed to conquer the Confederacy and convince the Border States to emancipate their slaves.