By Kaleena Fraga

In terms of crazy presidential campaigns, 2016 has nothing on 1968. The election of 1968 saw horrifying violence, the shattering of the Democratic party along lines of civil rights and Vietnam, and the end of liberalism in the Republican party. The election of 1968 brought an incumbent president to his knees, and Richard Nixon to the White House. It changed everything, including how we think about presidential campaigns and state primaries.

Today, many Americans will cast a ballot. Midterm elections usually aren’t as attention-grabbing as presidential ones, yet this year Americans have been told that this is the most important election of their life. Certainly, given recent violence, the stakes feel high.

No, 2016 has nothing on 1968. But 2020 could be another wild-ride. As the country turns out to the polls, we look back at the midterm election of 1966, and the seeds planted that year that burst through the soil in 1968.

Two years earlier, Lyndon Johnson had won a landslide victory, winning the election in his own right after serving the rest of John F. Kennedy’s term. Meanwhile, the Republicans had suffered a terrible defeat under the banner of Barry Goldwater, who infamously declared at the Republican convention that “extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice. And moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.” Johnson won a stunning 486 electoral votes to Goldwater’s 52. He took every state except for Arizona, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina.

The Republican party, pundits declared, was done.

Controlling both houses of Congress and the White House, Lyndon Johnson and the Democrats seemed unstoppable. They passed Johnson’s Great Society programs, including Medicare, and legislation that strengthened civil rights and voting rights. But as Johnson’s Great Society expanded, so did the conflict in Vietnam.

In 1966, tides had shifted. The public paid more attention to Vietnam, where they could see scant evidence of American victories. The economy began to slow. Race riots erupted across the nation. Johnson saw his popularity drop to below 45%. Republicans saw their opportunity. And they fought. Hard.

Determined to help restore the party to power (and to set himself up as a presidential candidate in 1968) Richard Nixon leapt into the fray. Nixon had not won an election since 1956, as Dwight Eisenhower’s vice president. After his failed bid for governor of California, he had bitterly told the press that they “would not have Nixon to kick around anymore.” And yet the former vice president had quietly been making moves behind the scenes. In the final months before the 1966 election, Nixon campaigned for 86 Republican candidates down the ballot. In the end, 59 of them won their elections.

“Tricky Dick”, thought to be politically dead, gained a lot of friends in 1966. Friends who would answer the phone when he called about running for president in 1968.

Although it was not enough to wrest control of the government from Johnson and the Democrats, Republicans won 47 seats in the House, 3 in the Senate, and 8 governorships. His majorities reduced, Newsweek wrote, “in the space of a single autumn day… the 1,000 day reign of Lyndon I came to an end: The Emperor of American politics became just a President again.”

In 1966, Ronald Reagan became governor of California. George H.W. Bush won a House seat in Texas. Gerald Ford won his reelection campaign and became House Minority Leader, increasing his prominence on the national stage. Republicans, wounded after 1964, suddenly believed they could win again. And they did–seven out of the next ten presidential elections were won by the GOP.

From 1966, Johnson became increasingly unpopular and unable to push legislation like he had in the first two years of his term. In 1968, he stunned the nation by announcing he would not “seek, nor accept” the nomination of the presidency.

The election of 1968 was the most dramatic of the 20th century, but it all started in 1966. Today, Americans vote. Who knows what seeds the nation will plant today, that may bloom in 2020 or beyond?

front page to her decision to not bow to the Queen. The Guardian

front page to her decision to not bow to the Queen. The Guardian

young teenager. Her brothers were studying at the University, and Lucy attended college prep courses. Too young to establish a relationship, they reunited years later when they were both members of a wedding party and married in 1852 when he was thirty and she was twenty-one. Lucy was a major influence on Hayes’ life during his entry into politics. The Ohio-born Hayes followed a fairly typical trajectory to the White House, checking off many of the most common boxes for U.S. presidents—he was educated at Harvard Law School and opened a law practice before serving in the military, then became a Congressman, and then Governor of Ohio. He won the presidency as the Republican nominee in 1876 and moved with Lucy and their family to Washington.

young teenager. Her brothers were studying at the University, and Lucy attended college prep courses. Too young to establish a relationship, they reunited years later when they were both members of a wedding party and married in 1852 when he was thirty and she was twenty-one. Lucy was a major influence on Hayes’ life during his entry into politics. The Ohio-born Hayes followed a fairly typical trajectory to the White House, checking off many of the most common boxes for U.S. presidents—he was educated at Harvard Law School and opened a law practice before serving in the military, then became a Congressman, and then Governor of Ohio. He won the presidency as the Republican nominee in 1876 and moved with Lucy and their family to Washington. The “Lemonade Lucy” moniker was not a title used during Lucy’s lifetime, but a name used by journalists, political cartoonists, and historians to poke fun at the strict nature of the First Family of teetotalers. Later historians credited Lucy’s husband with the decision not to serve liquor in the White House. As Emily Apt Greer, author of F

The “Lemonade Lucy” moniker was not a title used during Lucy’s lifetime, but a name used by journalists, political cartoonists, and historians to poke fun at the strict nature of the First Family of teetotalers. Later historians credited Lucy’s husband with the decision not to serve liquor in the White House. As Emily Apt Greer, author of F

book she’d purchased for her niece, which she’d discovered portrayed women as unequal to men. The note was a warning to read the book with a grain of salt. Abigail wrote: “I will never consent to have our sex considered in an inferior point of light.”

book she’d purchased for her niece, which she’d discovered portrayed women as unequal to men. The note was a warning to read the book with a grain of salt. Abigail wrote: “I will never consent to have our sex considered in an inferior point of light.” Abigail Adams was the first First Lady to live in the White House. She and John Adams moved to Washington D.C. from Philadelphia once the mansion was finished. As she wrote a friend, the executive mansion was huge and sparse. “It is habitable by fires in every part, thirteen of which we are obliged to keep daily, or sleep in wet and damp places.” Abigail used today’s East Room to dry the family’s

Abigail Adams was the first First Lady to live in the White House. She and John Adams moved to Washington D.C. from Philadelphia once the mansion was finished. As she wrote a friend, the executive mansion was huge and sparse. “It is habitable by fires in every part, thirteen of which we are obliged to keep daily, or sleep in wet and damp places.” Abigail used today’s East Room to dry the family’s

Nellie herself was bright–she had a gift for languages, and studied French, German, Latin and Greek. She wrote in her diary that, “A book has more fascination for me than anything else.” Nellie wanted to continue her education–her brothers went to Yale and Harvard–but her father told her he could not afford to send her to college. Anyway, she was expected to find herself a husband, instead.

Nellie herself was bright–she had a gift for languages, and studied French, German, Latin and Greek. She wrote in her diary that, “A book has more fascination for me than anything else.” Nellie wanted to continue her education–her brothers went to Yale and Harvard–but her father told her he could not afford to send her to college. Anyway, she was expected to find herself a husband, instead. Although some muttered that Nellie should focus more on “the simple duties of First Lady,” Nellie was equally eager to expand this role. Upsetting many New Yorkers, Nellie stated that she wanted to make Washington D.C. a social hub for Americans. Nellie set out to beautify the city. From her time abroad, Nellie had fallen in love with Japanese cherry trees and brought one hundred to Washington. When the mayor of Tokyo heard of this project, he sent 2,000 more.

Although some muttered that Nellie should focus more on “the simple duties of First Lady,” Nellie was equally eager to expand this role. Upsetting many New Yorkers, Nellie stated that she wanted to make Washington D.C. a social hub for Americans. Nellie set out to beautify the city. From her time abroad, Nellie had fallen in love with Japanese cherry trees and brought one hundred to Washington. When the mayor of Tokyo heard of this project, he sent 2,000 more. dreamed of in Taft’s administration. It certainly wanted for her influence. Without her, Taft was not able to play the dynamic social role he needed to fill the shoes of his bombastic predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt.

dreamed of in Taft’s administration. It certainly wanted for her influence. Without her, Taft was not able to play the dynamic social role he needed to fill the shoes of his bombastic predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt.

unveiling of their official portraits. Bush’s father and fellow president George H.W. Bush tagged along too. It was a light hearted occasion, with friendly barbs on both sides.

unveiling of their official portraits. Bush’s father and fellow president George H.W. Bush tagged along too. It was a light hearted occasion, with friendly barbs on both sides. In 1989, Ronald and Nancy Reagan were invited to the White House for the unveiling of their official portraits. Reagan

In 1989, Ronald and Nancy Reagan were invited to the White House for the unveiling of their official portraits. Reagan  because he thought it made him look like a “mewing cat.” The second painter he hired, John Singer Sargent, found him to be a

because he thought it made him look like a “mewing cat.” The second painter he hired, John Singer Sargent, found him to be a

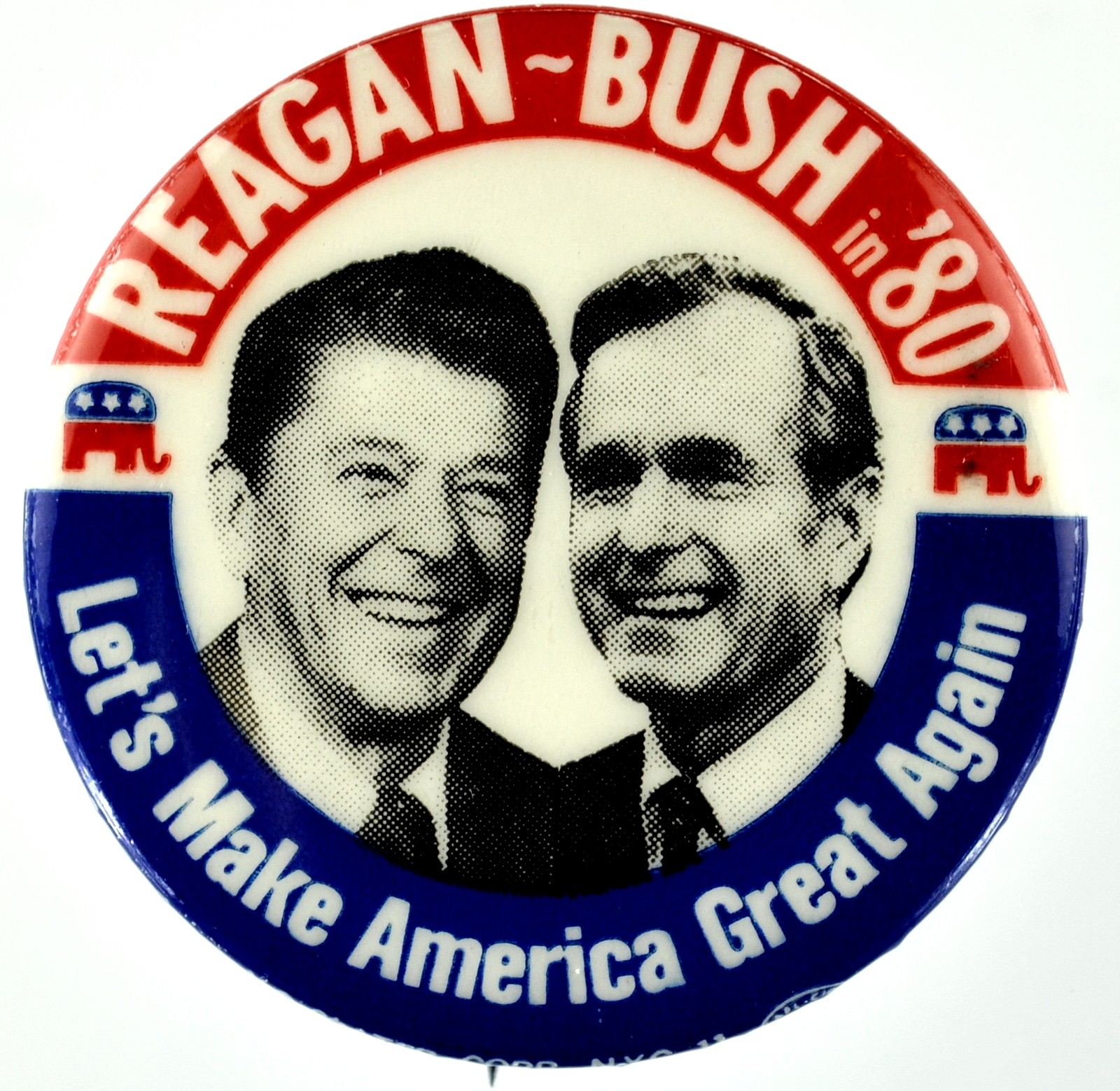

4. Reagan-Bush ran a slogan in 1980 that will sound familiar to many Americans today: “Let’s Make America Great Again.”

4. Reagan-Bush ran a slogan in 1980 that will sound familiar to many Americans today: “Let’s Make America Great Again.” enthusiastic. The New York Times called the run up to the endorsement “one of Washington’s longest-running and least suspenseful political dramas,” after Reagan insisted on waiting for the end of the Republican primary to announce his pick. Despite his nickname as the “Great Communicator” and Bush’s eight years of service as VP, Reagan flubbed Bush’s name during the endorsement, pronouncing it George Bosh.

enthusiastic. The New York Times called the run up to the endorsement “one of Washington’s longest-running and least suspenseful political dramas,” after Reagan insisted on waiting for the end of the Republican primary to announce his pick. Despite his nickname as the “Great Communicator” and Bush’s eight years of service as VP, Reagan flubbed Bush’s name during the endorsement, pronouncing it George Bosh.