By Kaleena Fraga

(to listen to a version of this piece in podcast form click here)

John Quincy Adams, America’s sixth president and the son of the nation’s second, had a reputation as a prickly, aloof man. He was a one-term president and by no means a popular one–yet he came to be seen as a man of iron principle and honesty, even in the face of political pressure from his own party. Politicians of his ilk are largely missing from the political landscape today.

I: Switching Parties

Adams, the son of one of America’s most prominent Federalists, entered the Senate in 1803 as a Federalist himself. Yet he remained distant from his colleagues. In an era of hyper-partisanship in which Federalists accused the Republicans of colluding with France, and the Republicans accused the Federalists of colluding with England (sound familiar?) Adams stubbornly trod his own path. He supported both President Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase and the administration’s hardline on England, which his fellow Federalists opposed. His father, former president John Adams wrote:

“You are supported by no Party. You have too honest a heart, too independent a Mind and too brilliant Talents to be sincerely and confidentially trusted by any Man who is under the Dominion of Party Maxims or Party Feelings.”

His stubborn refusal to fall in line with the Federalists, and his support of Jefferson, cost Adams his seat in the Senate, his place in the party, and many friends back in Boston. To Adams, it was a matter of principle, and a matter of what he thought was right and wrong according to the U.S. Constitution.

This sort of political courage is rare in Washington today. To be fair to today’s politicians, the landscape has changed. There is pressure from lobbyists, constituents on social media, and from within the party itself to toe the party line. Political purity tests are the cause celebre of today, and politicians that stray too far from the party line face possible challenges from the left or right of their own parties. It’s doubtful that Adams–with his iron will and stubborn personality–would be swayed. But it’s also likely that he’d never make it to Congress (or the presidency) in the first place.

II: As President

John Quincy Adams’s presidency spanned a divisive time in American. After the relative political tranquility of Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe’s presidencies–“the Era of Good Feelings”–, in which the Republicans enjoyed almost unanimous support, Adams entered office as the country’s political unity began to fray. The nature of campaigning had also begun to change–in the day of George Washington, a man had to practically be dragged to the presidency by his fellow citizens. In John Quincy Adams’ day, it was becoming permissible for a man or his friends to campaign actively.

The electoral system in America of the 1820s had begun to evolve as more states joined the union, and although there wasn’t a uniform way of voting, regular people had more of a sway than ever before. Adams’ political rival, Andrew Jackson, supported this democratic uprising. The fact that Adams entered office in 1824 under the auspice of a “corrupt bargain”–Jackson won the most electoral votes, but not a majority, so the election was sent to the House of Representatives where Adams was alleged to have struck a deal with Henry Clay–only increased the divide between the two parties.

John Dickerson’s piece for the Atlantic The Hardest Job in the World postulates that the presidency has become a beast unmanageable for one man, and that the current system of campaigning rewards skills that aren’t necessary applicable or important to the presidency once he/she is in the office. Campaigning rewards skills like charisma and debate; the office requires management and governance. Adams would probably agree with Dickerson–part of his cohort’s campaign against Jackson was that the fiery formal general couldn’t spell and lacked the necessary political experience to be president. Adams likely couldn’t be elected today, and perhaps was the last person to be elected based on political merits, rather than his power of campaigning. James Traub, an Adams biographer, notes of Jackson’s victory over Adams in 1828: “Of course, the whole episode was founded on the archaic assumption that Americans would not elect a man who couldn’t spell or hold his temper.”

III: Post Presidency

Adams served a single term as president–becoming only the second man to be voted out after four years, after his father, John Adams. But Adams refused to be cast into political obscurity. As part of his upbringing in Massachusetts, his parents had always encouraged him to find ways to be useful. “Usefulness” is also a reason James Comey invoked to justify writing his book after he was fired by Donald Trump.

When the opportunity rose for Adams to join the House of Representatives, he took it. Although many of his friends and family feared it would be degrading for an ex-president to join a lower chamber, Adams refuted this logic, saying it wouldn’t be at all degrading to serve “as a selectman of his town, if elected thereto by the people.” He joined the House in 1830 and would serve until his death in 1848–Adams literally collapsed on the House floor and died in the Speaker’s office.

As a member of the House, Adams took on slavery as his cause. Although he never labelled himself an abolitionist–at the time, abolitionists were hated by both the North and South as dangerous rabble rousers–Adams became a thorn in the side of the “slavocracy.” He insisted on introducing petitions to the House which raised questions about slavery–and continued to do so even after the passage of the gag rule, which forbid any such thing on the House floor. A rival Congressman once tried to bait Adams, reading back a line that he’d spoken to a group of black citizens: “The day of your redemption is bound to come. It may come in peace or it may come in blood; but whether in peace or blood let it come.” The Congressman read the line twice. He reminded his colleagues what this meant–emancipation and maybe civil war. Adams replied:

“I say now let it come. Though it cost the blood of millions of white men let it come. Let justice be done though the heavens fall.”

Although the political climate was not at all amenable to this sort of thought–indeed, at the time such a statement was shocking, and Adams received his fair share of death threats–Adams never cowered from a controversial political issue that he thought was right, or wrong. He challenged the slavocracy as a Congressman and as a lawyer, when he defended the men and women of the Amistad and won their freedom.

In today’s increasingly partisan climate, where politicians are falling over themselves to move further to the left or right in order to move up the ladder, a politician like Adams, who sticks to his principles even under immense political pressure, would be a welcome change.

While Eisenhower maintained a healthy distance from the campaign, Nixon leapt into the fray. He put up a fight for the presidency that would embitter many against him for the rest of his political career, including Harry Truman, who interpreted Nixon’s messaging as a sly way of calling him a traitor. (Truman would later insist that Nixon had personally accused him of treason, although no evidence exists to support this). Even in Nixon’s lowest point of the campaign–when he was forced to defend his use of a political slush fund in the now famous “Checkers” speech–he was sure to add at the end that electing Eisenhower was important because the Democrats had left the government riddled with Communists and corruption.

While Eisenhower maintained a healthy distance from the campaign, Nixon leapt into the fray. He put up a fight for the presidency that would embitter many against him for the rest of his political career, including Harry Truman, who interpreted Nixon’s messaging as a sly way of calling him a traitor. (Truman would later insist that Nixon had personally accused him of treason, although no evidence exists to support this). Even in Nixon’s lowest point of the campaign–when he was forced to defend his use of a political slush fund in the now famous “Checkers” speech–he was sure to add at the end that electing Eisenhower was important because the Democrats had left the government riddled with Communists and corruption.

does not eat in public.” A waitress later told UPI that the queen did not eat, but she did

does not eat in public.” A waitress later told UPI that the queen did not eat, but she did

In 1842 Whitman attended a lecture given by Ralph Waldo Emerson, where Emerson predicted that America would soon have its own poet who would write about the American experience in a uniquely American style. “When he lifts his great voice, men gather to him and forget all that is past, and then his words are to the hearers, pictures of all history,” Emerson said.

In 1842 Whitman attended a lecture given by Ralph Waldo Emerson, where Emerson predicted that America would soon have its own poet who would write about the American experience in a uniquely American style. “When he lifts his great voice, men gather to him and forget all that is past, and then his words are to the hearers, pictures of all history,” Emerson said. the Battle of Fredericksburg, where the Union was badly defeated. Whitman rushed to the battlefield, only to find that his brother was minimally injured. Whitman stayed with his brother for over a week and witnessed the realities of war. “Living so close to the front, to the dressing stations and the hospital tents pitched on the frozen ground, the fresh barrel-stave markers in the burial field, the vexed Rappahannock, and the ruins of Fredericksburg, he saw ‘what well men and sick men and mangled men endure,’” Justin Kaplan wrote in Walt Whitman: A Life. Whitman began writing down these observations, later using them for his “Drum-Taps” poems.

the Battle of Fredericksburg, where the Union was badly defeated. Whitman rushed to the battlefield, only to find that his brother was minimally injured. Whitman stayed with his brother for over a week and witnessed the realities of war. “Living so close to the front, to the dressing stations and the hospital tents pitched on the frozen ground, the fresh barrel-stave markers in the burial field, the vexed Rappahannock, and the ruins of Fredericksburg, he saw ‘what well men and sick men and mangled men endure,’” Justin Kaplan wrote in Walt Whitman: A Life. Whitman began writing down these observations, later using them for his “Drum-Taps” poems.

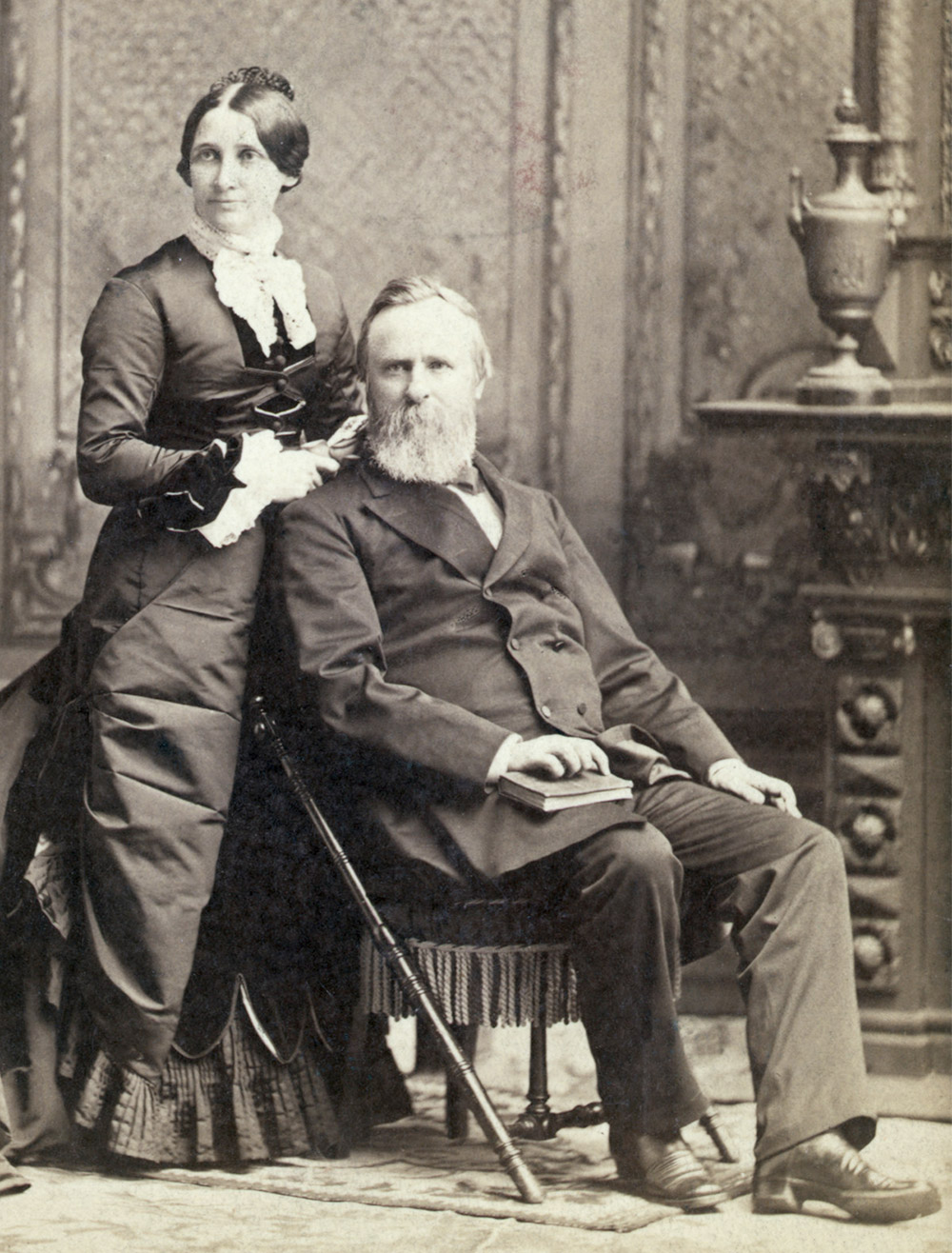

young teenager. Her brothers were studying at the University, and Lucy attended college prep courses. Too young to establish a relationship, they reunited years later when they were both members of a wedding party and married in 1852 when he was thirty and she was twenty-one. Lucy was a major influence on Hayes’ life during his entry into politics. The Ohio-born Hayes followed a fairly typical trajectory to the White House, checking off many of the most common boxes for U.S. presidents—he was educated at Harvard Law School and opened a law practice before serving in the military, then became a Congressman, and then Governor of Ohio. He won the presidency as the Republican nominee in 1876 and moved with Lucy and their family to Washington.

young teenager. Her brothers were studying at the University, and Lucy attended college prep courses. Too young to establish a relationship, they reunited years later when they were both members of a wedding party and married in 1852 when he was thirty and she was twenty-one. Lucy was a major influence on Hayes’ life during his entry into politics. The Ohio-born Hayes followed a fairly typical trajectory to the White House, checking off many of the most common boxes for U.S. presidents—he was educated at Harvard Law School and opened a law practice before serving in the military, then became a Congressman, and then Governor of Ohio. He won the presidency as the Republican nominee in 1876 and moved with Lucy and their family to Washington. The “Lemonade Lucy” moniker was not a title used during Lucy’s lifetime, but a name used by journalists, political cartoonists, and historians to poke fun at the strict nature of the First Family of teetotalers. Later historians credited Lucy’s husband with the decision not to serve liquor in the White House. As Emily Apt Greer, author of F

The “Lemonade Lucy” moniker was not a title used during Lucy’s lifetime, but a name used by journalists, political cartoonists, and historians to poke fun at the strict nature of the First Family of teetotalers. Later historians credited Lucy’s husband with the decision not to serve liquor in the White House. As Emily Apt Greer, author of F

Edith met Woodrow Wilson during a chance encounter at the White House. His first wife, Ellen, had died of Bright’s disease only seven months earlier. They had a quick and passionate courtship which

Edith met Woodrow Wilson during a chance encounter at the White House. His first wife, Ellen, had died of Bright’s disease only seven months earlier. They had a quick and passionate courtship which  answer to what the government should do if the president became unable to perform his duties. Wilson wasn’t dead, so there didn’t seem to be a reason for the vice president to step into his role. Without the 25th amendment, Congress and the Cabinet had no real power to act (and the extent of Wilson’s condition was kept top secret). To Edith, protective of her husband and his presidency, the answer was clear.

answer to what the government should do if the president became unable to perform his duties. Wilson wasn’t dead, so there didn’t seem to be a reason for the vice president to step into his role. Without the 25th amendment, Congress and the Cabinet had no real power to act (and the extent of Wilson’s condition was kept top secret). To Edith, protective of her husband and his presidency, the answer was clear.

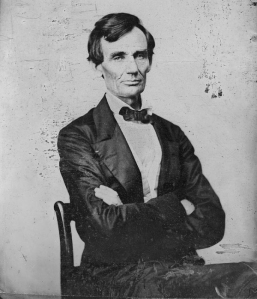

Lincoln wasn’t exactly smitten with Mary Todd. After they got engaged, Lincoln had second thoughts and he tried to get out of their engagement. Several of Lincoln’s friends recollected his misgivings about Mary, which Michael Burlingame documented in his book

Lincoln wasn’t exactly smitten with Mary Todd. After they got engaged, Lincoln had second thoughts and he tried to get out of their engagement. Several of Lincoln’s friends recollected his misgivings about Mary, which Michael Burlingame documented in his book  General Ulysses S. Grant at his first appearance in Washington, D.C. as the top general in the Union army. That reception, a journalist noted, was the first time Abraham Lincoln wasn’t the center of attention in the East Room. Grant was elected president in the first election after Lincoln’s assassination. He might have been assassinated with Lincoln on April 14, 1865, if Mary Todd Lincoln hadn’t thrown a tantrum a few weeks earlier in front of Grant’s wife Julia Dent Grant. Even though the morning newspaper reported that the Lincolns and the Grants would attend a showing of

General Ulysses S. Grant at his first appearance in Washington, D.C. as the top general in the Union army. That reception, a journalist noted, was the first time Abraham Lincoln wasn’t the center of attention in the East Room. Grant was elected president in the first election after Lincoln’s assassination. He might have been assassinated with Lincoln on April 14, 1865, if Mary Todd Lincoln hadn’t thrown a tantrum a few weeks earlier in front of Grant’s wife Julia Dent Grant. Even though the morning newspaper reported that the Lincolns and the Grants would attend a showing of

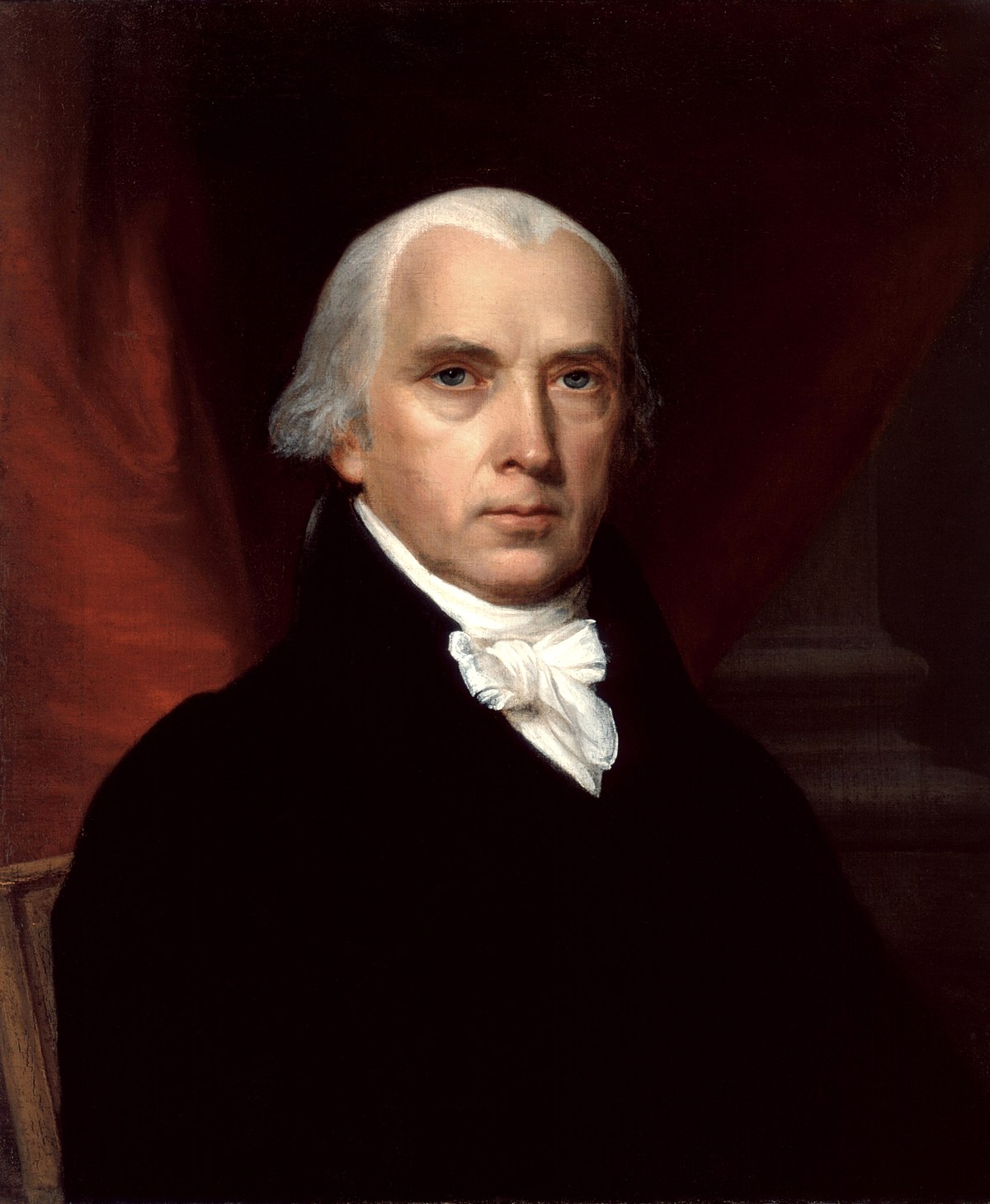

In David McCullough biography’s of Madison-foe John Adams, the nation’s fourth president is described as “a tiny, sickly-looking man who weighed little more than a hundred pounds and dressed always in black.” When Dolley Madison caught his eye and he asked for an audience with her (bonus trivia: mutual friend Aaron Burr set them up), she wrote her sister that “the great, little Madison” wanted to meet her. Great because of Madison’s political reputation; little because at 5’7, Dolley Madison was several inches taller than her future husband.

In David McCullough biography’s of Madison-foe John Adams, the nation’s fourth president is described as “a tiny, sickly-looking man who weighed little more than a hundred pounds and dressed always in black.” When Dolley Madison caught his eye and he asked for an audience with her (bonus trivia: mutual friend Aaron Burr set them up), she wrote her sister that “the great, little Madison” wanted to meet her. Great because of Madison’s political reputation; little because at 5’7, Dolley Madison was several inches taller than her future husband. the James Madison biography The Three Lives of James Madison by Noah Feldman, Feldman writes that Dolley was instrumental in forming Madison’s ability to converse with diplomats and their wives. “Under Dolley’s tutelage,” Feldman writes, “Madison developed what would become a lifelong habit of telling witty stories after dinner, the ideal venue for his particular brand of dry wit.”

the James Madison biography The Three Lives of James Madison by Noah Feldman, Feldman writes that Dolley was instrumental in forming Madison’s ability to converse with diplomats and their wives. “Under Dolley’s tutelage,” Feldman writes, “Madison developed what would become a lifelong habit of telling witty stories after dinner, the ideal venue for his particular brand of dry wit.” wanted to wait for his return. According to an account by Paul Jennings, a man born into slavery at Madison’s estate of Montpelier and then working at the White House, the table had been set for dinner when a rider came charing to the mansion with the message that they must evacuate immediately. Dolley wrote her sister that she insisted on waiting until they could unscrew the portrait of George Washington from the wall.

wanted to wait for his return. According to an account by Paul Jennings, a man born into slavery at Madison’s estate of Montpelier and then working at the White House, the table had been set for dinner when a rider came charing to the mansion with the message that they must evacuate immediately. Dolley wrote her sister that she insisted on waiting until they could unscrew the portrait of George Washington from the wall.