By Kaleena Fraga

The teenager survivors of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School have taken to the streets to protest lax gun laws–laws endorsed by the National Rifle Association, which they say allowed their ex-classmate to legally and easily purchase a gun and murder 17 of their peers.

Although sixty-six percent of Americans have expressed support for stronger gun control, the rhetoric between the two sides is hotter than ever. Many conservatives have doubled down in their support of the N.R.A., going after the student survivors of the Parkland shooting as “crisis actors” or mocking them on Twitter.

So it’s worth noting that one prominent conservative, George H.W. Bush, walked away from the N.R.A. in 1995 when he found that their messaging had grown too fiery in the wake of the Oklahoma City bombing. It’s the kind of quiet courage that defined much of his time in public life–and an action that would be met with scorn by many on the right today.

So it’s worth noting that one prominent conservative, George H.W. Bush, walked away from the N.R.A. in 1995 when he found that their messaging had grown too fiery in the wake of the Oklahoma City bombing. It’s the kind of quiet courage that defined much of his time in public life–and an action that would be met with scorn by many on the right today.

The N.R.A had been on the offensive since 1993, when federal agents stormed a compound belonging to a cult called the Branch Davidians. The siege left dead on both sides. In its aftermath, as the Washington Post noted, “the ATF raid on the Branch Davidian compound only proved what [many N.R.A members] have been saying for years — that the Treasury Department agency is recklessly out of control, smashing into private homes to trample basic civil rights.”

In between the siege at Waco and the Oklahoma City bombing, N.R.A. executive vice president Wayne LaPierre (in the same role he holds today), wrote a “special report” in the magazine American Rifleman. Among other things, it alleged that LaPierre had received a “secret” document, which warned that “the full scale war to crush [Americans’] gun rights has not only begun, but is well underway.”

A week before the bombing in Oklahoma City, LaPierre also signed a fund-raising letter that warned that President Clinton’s ban on assault weapons would result in “jackbooted Government thugs [with] more power to take away our constitutional rights, break in our doors, seize our guns, destroy our property and even injure and kill us.” The N.R.A. in 1995 endorsed the idea that the government was coming for Americans’ guns and their freedom. They pointed to Waco as the prime example.

Six days later, Timothy McVeigh bombed the Alfred P. Murrah Federal building in Oklahoma City.

McVeigh had been an NRA member for four years. He embraced many of the same positions as the NRA—he was a gun owner and believed that the government wanted to take his guns away. The Oklahoma City bombing killed 168 people, many of them federal employees. The N.R.A. found itself under increased scrutiny—it had pushed the idea that government could be the enemy of the people, and someone had taken this rhetoric and acted upon it.

Yet even after the bombing, LaPierre refused to soften his language. When asked if,  in light of the tragedy, he’d like to take back what he’d said, LaPierre replied, “That’s like saying the weather report in Florida on the hurricane caused the damage rather than the hurricane.”

in light of the tragedy, he’d like to take back what he’d said, LaPierre replied, “That’s like saying the weather report in Florida on the hurricane caused the damage rather than the hurricane.”

To George H.W. Bush the rhetoric and the refusal by the N.R.A to repudiate LaPierre had crossed a line.

He wrote a letter to Thomas L. Washington, the president of the N.R.A. resigning his membership. The letter, in part, stated that Bush felt:

“outraged when, even in the wake of the Oklahoma City tragedy, Mr. Wayne LaPierre…defended his attack on federal agents as ‘jack-booted thugs.’ To attack Secret Service agents or A.T.F. people or any government law enforcement people as ‘wearing Nazi bucket helmets and black storm trooper uniforms’ wanting to ‘attack law abiding citizens’ is a vicious slander on good people.”

Bush went on to name several Secret Service agents and A.T.F. members whom he knew, and whom he endorsed as honorable people. One man, a Secret Service agent named Al Whicher who had served on Bush’s security detail, had been killed in Oklahoma City. The men that Bush listed, he wrote to Washington, “were no Nazis.” The officers he had known, Bush went on, “would [never] give the government’s ‘go ahead to harass, intimidate, even murder law abiding citizens.’ (Your words).”

Bush acknowledged that he was a gun owner and an avid hunter. He agreed with the N.R.A’s objectives and believed in the importance of its education and training.

“However,” he wrote, “your broadside against Federal agents deeply offends my own sense of decency and honor; and it offends my concept of service to country. It indirectly slanders a wide array of government law enforcement officials, who are out there, day and night, laying their lives on the line for all of us.”

In light of this, Bush wrote, he would resign from the N.R.A., effective immediately.

In between 1995 and 2018, the N.R.A.’s rhetoric hasn’t changed. If anything, it has become angrier, more reactionary. At the 2017 Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) LaPierre warned that the “left -wing socialist brigade” sought to destroy “Western civilization.” At CPAC 2018, a few weeks after the Parkland shooting, LaPierre stated that the goals of the country’s “elite” was to “eliminate the Second Amendment and our firearms freedoms so they can eradicate all individual freedoms.” Gun control advocates, he said, “don’t care about our children. They want to make us all less free.”

Although Bush had been out of office for two years at the time of his resignation, he showed political courage that seems to be lacking in Washington today. Two days after the Parkland shooting President Donald Trump tweeted that “[La Pierre]…and the folks who work so hard at the @NRA are Great People and Great American Patriots. They love our Country  and will do the right thing.” Trump is the first president since George H.W. Bush to be a member of the N.R.A.

and will do the right thing.” Trump is the first president since George H.W. Bush to be a member of the N.R.A.

Yet for a few days after the shooting it seemed that the survivors of Parkland and other advocates of gun control might find a surprising ally in the president. During a televised meeting Trump stated that while he “loved the N.R.A.” action was needed. He also appeared to endorse the idea that guns should be taken from anyone who seemed to be threatening violence. “Take the guns first,” Trump said. “Go through due process second.”

But any hope at a bipartisan solution–or for the president to show any political bravery in the face of the N.R.A.–was short lived. Soon after a visit in the Oval Office between the president and N.R.A. representatives Trump reversed course, endorsing N.R.A ideas like arming teachers, and tweeting that gun control did not have “much political support (to put it mildly).”

To change the America’s gun laws, then, the nation looks not toward the White House or any political or moral leaders, but rather to a growing group of young students who are determined to end gun violence once and for all.

book she’d purchased for her niece, which she’d discovered portrayed women as unequal to men. The note was a warning to read the book with a grain of salt. Abigail wrote: “I will never consent to have our sex considered in an inferior point of light.”

book she’d purchased for her niece, which she’d discovered portrayed women as unequal to men. The note was a warning to read the book with a grain of salt. Abigail wrote: “I will never consent to have our sex considered in an inferior point of light.” Abigail Adams was the first First Lady to live in the White House. She and John Adams moved to Washington D.C. from Philadelphia once the mansion was finished. As she wrote a friend, the executive mansion was huge and sparse. “It is habitable by fires in every part, thirteen of which we are obliged to keep daily, or sleep in wet and damp places.” Abigail used today’s East Room to dry the family’s

Abigail Adams was the first First Lady to live in the White House. She and John Adams moved to Washington D.C. from Philadelphia once the mansion was finished. As she wrote a friend, the executive mansion was huge and sparse. “It is habitable by fires in every part, thirteen of which we are obliged to keep daily, or sleep in wet and damp places.” Abigail used today’s East Room to dry the family’s

Barbara Bush met her husband at sixteen and married him four years later, after his brush with death during WWII. Before marriage Mrs. Bush had enrolled in Smith College–she was a voracious reader as a girl–and helped out in the war effort by

Barbara Bush met her husband at sixteen and married him four years later, after his brush with death during WWII. Before marriage Mrs. Bush had enrolled in Smith College–she was a voracious reader as a girl–and helped out in the war effort by  own political views, she was more outspoken before and after H.W.’s term in office. During his vice presidential run she

own political views, she was more outspoken before and after H.W.’s term in office. During his vice presidential run she

Nellie herself was bright–she had a gift for languages, and studied French, German, Latin and Greek. She wrote in her diary that, “A book has more fascination for me than anything else.” Nellie wanted to continue her education–her brothers went to Yale and Harvard–but her father told her he could not afford to send her to college. Anyway, she was expected to find herself a husband, instead.

Nellie herself was bright–she had a gift for languages, and studied French, German, Latin and Greek. She wrote in her diary that, “A book has more fascination for me than anything else.” Nellie wanted to continue her education–her brothers went to Yale and Harvard–but her father told her he could not afford to send her to college. Anyway, she was expected to find herself a husband, instead. Although some muttered that Nellie should focus more on “the simple duties of First Lady,” Nellie was equally eager to expand this role. Upsetting many New Yorkers, Nellie stated that she wanted to make Washington D.C. a social hub for Americans. Nellie set out to beautify the city. From her time abroad, Nellie had fallen in love with Japanese cherry trees and brought one hundred to Washington. When the mayor of Tokyo heard of this project, he sent 2,000 more.

Although some muttered that Nellie should focus more on “the simple duties of First Lady,” Nellie was equally eager to expand this role. Upsetting many New Yorkers, Nellie stated that she wanted to make Washington D.C. a social hub for Americans. Nellie set out to beautify the city. From her time abroad, Nellie had fallen in love with Japanese cherry trees and brought one hundred to Washington. When the mayor of Tokyo heard of this project, he sent 2,000 more. dreamed of in Taft’s administration. It certainly wanted for her influence. Without her, Taft was not able to play the dynamic social role he needed to fill the shoes of his bombastic predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt.

dreamed of in Taft’s administration. It certainly wanted for her influence. Without her, Taft was not able to play the dynamic social role he needed to fill the shoes of his bombastic predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt.

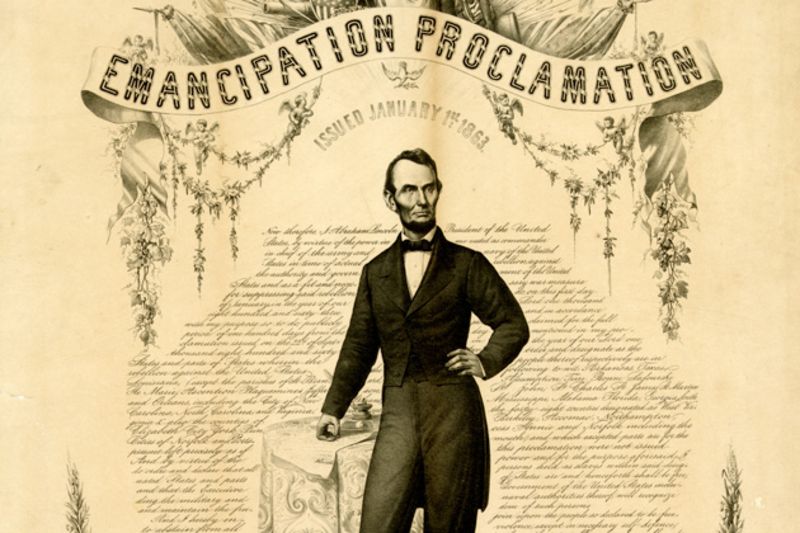

Racial violence perpetrated both sides of the conflict. That year, the Democratic Party ran a racist, anti-war campaign, warning that emancipation meant black people would move North in droves and force whites out of their homes. “The Constitution as it is, the Union as it was, and the negroes where they are,” was their campaign slogan. Democrats gained 34 seats in the House of Representatives, won gubernatorial races in New York and New Jersey, and won control of several state legislatures. In 1863, Horatio Seymour, the Democratic governor of New York, said, “I assure you I am your friend,” to anti-draft rioters who had lynched black doormen and burned down the Colored Orphan Asylum in New York City.

Racial violence perpetrated both sides of the conflict. That year, the Democratic Party ran a racist, anti-war campaign, warning that emancipation meant black people would move North in droves and force whites out of their homes. “The Constitution as it is, the Union as it was, and the negroes where they are,” was their campaign slogan. Democrats gained 34 seats in the House of Representatives, won gubernatorial races in New York and New Jersey, and won control of several state legislatures. In 1863, Horatio Seymour, the Democratic governor of New York, said, “I assure you I am your friend,” to anti-draft rioters who had lynched black doormen and burned down the Colored Orphan Asylum in New York City.  letter to Lincoln, “I have given the subject of arming the negro my hearty support. This, with the emancipation of the negro, is the heavyest blow yet given to the Confederacy … by arming the negro we have added a powerful ally. They will make good soldiers and taking them from the enemy weakens him in the same proportion they strengthen us. I am therefore most decidedly in favor of pushing this policy to the enlistment of a force sufficient to hold all the South falling into our hands and to aid in capturing more.”

letter to Lincoln, “I have given the subject of arming the negro my hearty support. This, with the emancipation of the negro, is the heavyest blow yet given to the Confederacy … by arming the negro we have added a powerful ally. They will make good soldiers and taking them from the enemy weakens him in the same proportion they strengthen us. I am therefore most decidedly in favor of pushing this policy to the enlistment of a force sufficient to hold all the South falling into our hands and to aid in capturing more.” Lincoln’s second inauguration happened on March 4, 1865, when Union victory was imminent. He closed his Second Inaugural Address by extending an olive branch to the defeated Confederates and looking ahead to Reconstruction: “With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and lasting peace among ourselves, and with all nations.”

Lincoln’s second inauguration happened on March 4, 1865, when Union victory was imminent. He closed his Second Inaugural Address by extending an olive branch to the defeated Confederates and looking ahead to Reconstruction: “With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and lasting peace among ourselves, and with all nations.”