By Kaleena Fraga

Happy Valentine’s Day from History First! Is the presidency romantic? Well, couples throughout history have thought so—multiple people have gotten married at the White House since the beginning of the 19th-century. Curiously, only one president has ever been married there.

Join us on a walk down the aisle. Here are some stories about weddings at the White House:

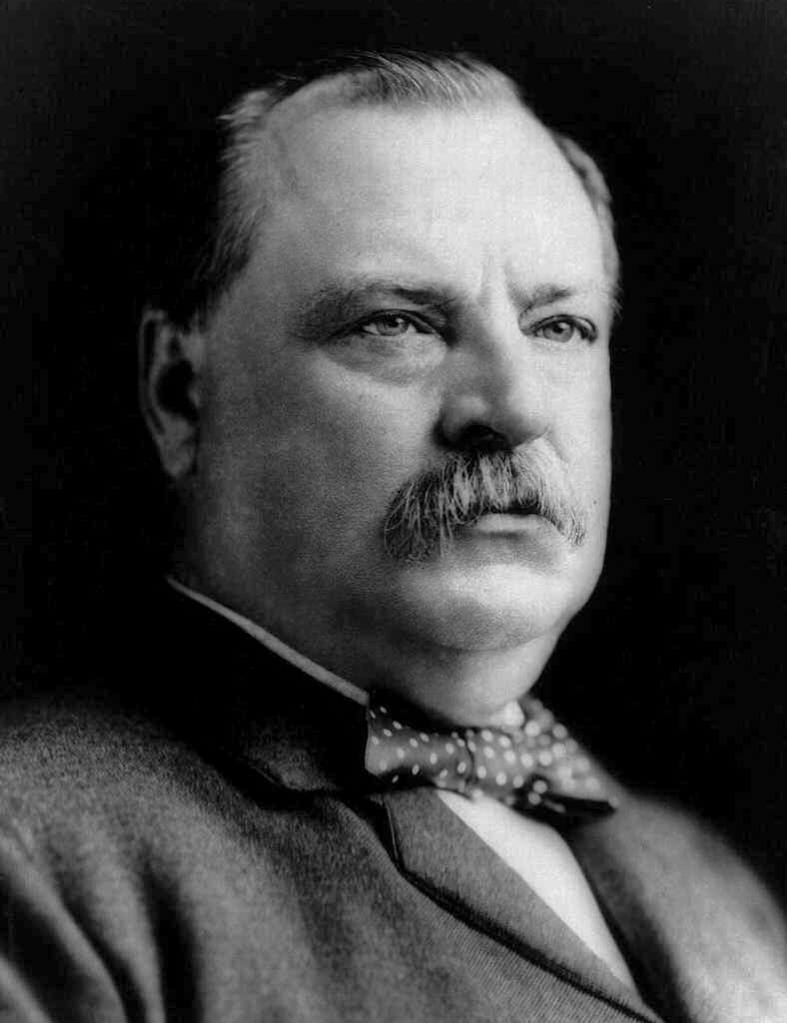

Grover Cleveland: The Only President to Get Married at the White House

History First has had a lot of love for Grover Cleveland, lately. We’ve written about his health scares and how he was the only non-consecutive president in American history. For a president most Americans don’t remember, Cleveland had a lot of “firsts” and “onlys”. One of these is his wedding. Grover Cleveland is the only president to have gotten married at the White House.

White House bachelors are a rare breed. Most were widowers or lost their wives during their administrations. Only three presidents married during their time in office: John Tyler, Woodrow Wilson, and Cleveland. For Tyler and Wilson, it was a second marriage. Tyler married his bride, Julia, in New York. Wilson married his, Edith, at her home in Washington D.C.

Grover Cleveland’s status as a bachelor had been a cause for concern during his campaign. A sex scandal emerged during his 1884 run in which a woman named Maria Halpin claimed that she had had Cleveland’s baby out of wedlock. This was embarrassing for Cleveland, but ultimately his supporters shrugged it off as “boys being boys.” Halpin was sent to an insane asylum; the baby was put up for adoption. #MeToo, this wasn’t.

And this is where it gets weird. Maria Halpin’s baby was named Oscar Folsom Cleveland—a combination of Cleveland’s name, and the name of his best friend, Oscar. Oscar had a daughter named Frances. (Do you see where this is going? If not, spoiler alert: Cleveland marries her.) Frances was younger than Cleveland—much younger. They first met when Frances was a baby, and Cleveland was 27 years old. In fact, Cleveland bought his future bride her first baby carriage.

When Oscar died, Cleveland became the executor of his estate. As such, his ties to the Folsom family remained deep even after Oscar’s death. When Frances went to college, Cleveland asked her mother for permission to write her letters.

They began to correspond—and Cleveland made sure her dorm room at Wells College was filled with flowers. When Frances and her mother visited the White House, their correspondence bloomed into romance. They were married on June 2, 1886. Cleveland was 49; Frances was 21.

So let’s talk about that.

The Clevelands’ White House Wedding

On May 28, 1886, the president had a surprise announcement for the country — in five days, he would marry Frances Folsom at the White House.

The invitation was short, to the point, and signed by the president:

“On Wednesday next at seven o’clock in the evening I shall be married to Miss Folsom at the White House.

We shall have a very quiet wedding, but I earnestly desire that [you] will be present on the occasion.”

Cleveland meant it when he said it would be a quiet wedding. Only 28 guests gathered on June 2nd, in the Blue Room at the White House, to witness the event.

“Accustomed as were the ladies gathered in the to the dazzle of rich costumes, they could barely restrain expressions of wonder and admiration at the beautiful picture presented by the bride,” the New York Times noted the next day. Frances wore a wedding dress with a six-foot long veil, decorated with orange blossoms, as popularized by Queen Victoria. During the ceremony, she promised to “honor, love, and keep” her new husband, as opposed to the traditional “honor, love, and obey.”

By all accounts, Frances Folsom and Grover Cleveland had a happy marriage. They had five children together. And, here, we find another first: their daughter, Esther, was the first—and only—president’s baby to be born at the White House.

How Many Other People Have Gotten Married at the White House?

The Clevelands may be the only presidential couple to wed at the White House, but they’re far from the only couple. There have been eighteen weddings at the White House since Dolley Madison’s sister got married there in 1812.

Mostly, White House weddings have featured presidential relatives—sons, daughters, nieces, etc.

Only twice has a non-relative married at the White House. In 1942, Harry Hopkins—an assistant to Franklin Roosevelt—married at the White House. In 2013—the most recent White House wedding—Barack Obama’s photographer, Pete Souza, married in the Rose Garden.

Of course, there are some downsides to getting married at the White House. The attention is intense, your ceremony might be drowned out by protests—depending on what the president has done, lately—and the White House is, of course, a public place. When Jenna Bush got married in 2008, she opted to hold the ceremony at her parents’ ranch in Texas.

—

Happy Valentine’s Day!

front page to her decision to not bow to the Queen. The Guardian

front page to her decision to not bow to the Queen. The Guardian

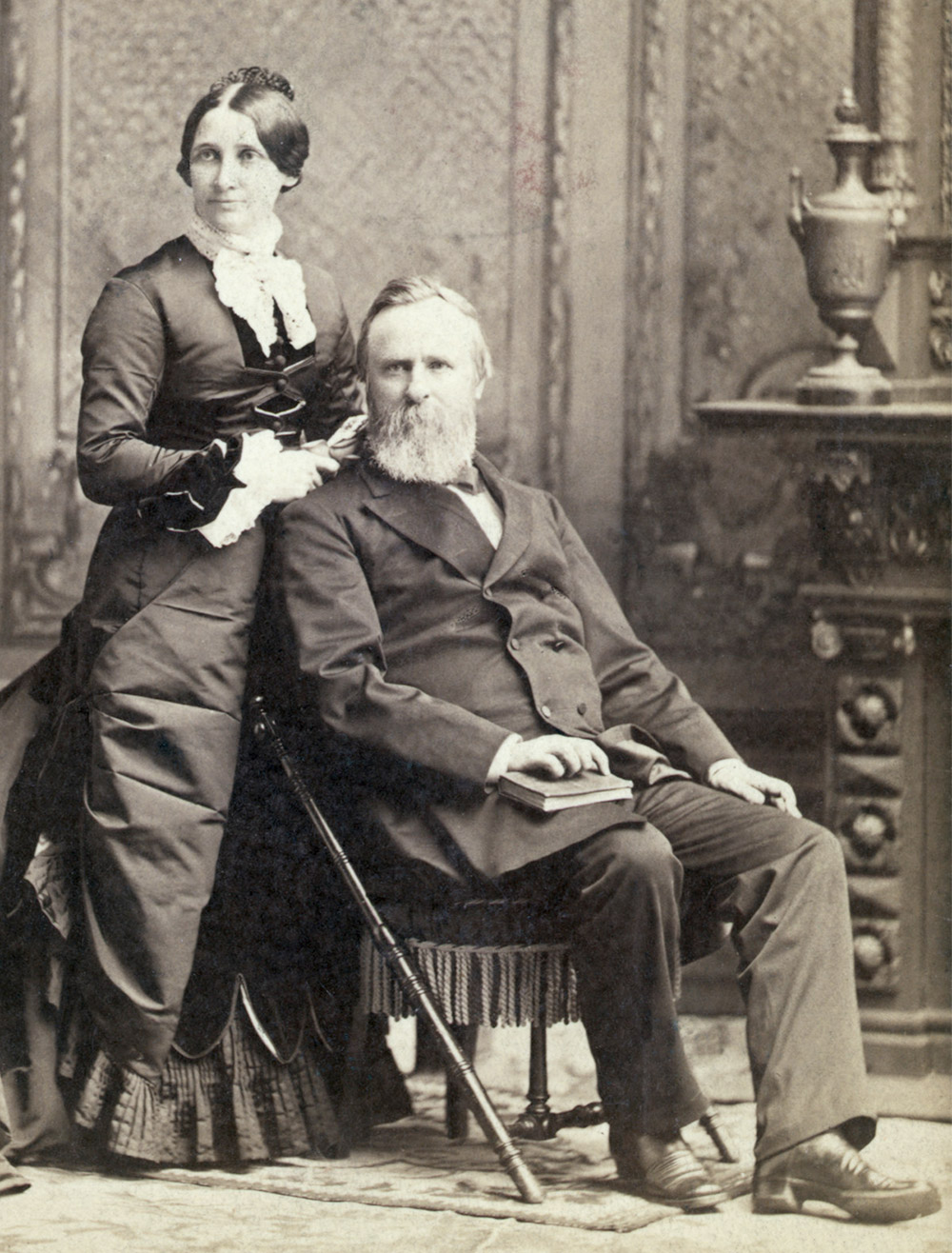

young teenager. Her brothers were studying at the University, and Lucy attended college prep courses. Too young to establish a relationship, they reunited years later when they were both members of a wedding party and married in 1852 when he was thirty and she was twenty-one. Lucy was a major influence on Hayes’ life during his entry into politics. The Ohio-born Hayes followed a fairly typical trajectory to the White House, checking off many of the most common boxes for U.S. presidents—he was educated at Harvard Law School and opened a law practice before serving in the military, then became a Congressman, and then Governor of Ohio. He won the presidency as the Republican nominee in 1876 and moved with Lucy and their family to Washington.

young teenager. Her brothers were studying at the University, and Lucy attended college prep courses. Too young to establish a relationship, they reunited years later when they were both members of a wedding party and married in 1852 when he was thirty and she was twenty-one. Lucy was a major influence on Hayes’ life during his entry into politics. The Ohio-born Hayes followed a fairly typical trajectory to the White House, checking off many of the most common boxes for U.S. presidents—he was educated at Harvard Law School and opened a law practice before serving in the military, then became a Congressman, and then Governor of Ohio. He won the presidency as the Republican nominee in 1876 and moved with Lucy and their family to Washington. The “Lemonade Lucy” moniker was not a title used during Lucy’s lifetime, but a name used by journalists, political cartoonists, and historians to poke fun at the strict nature of the First Family of teetotalers. Later historians credited Lucy’s husband with the decision not to serve liquor in the White House. As Emily Apt Greer, author of F

The “Lemonade Lucy” moniker was not a title used during Lucy’s lifetime, but a name used by journalists, political cartoonists, and historians to poke fun at the strict nature of the First Family of teetotalers. Later historians credited Lucy’s husband with the decision not to serve liquor in the White House. As Emily Apt Greer, author of F

Edith met Woodrow Wilson during a chance encounter at the White House. His first wife, Ellen, had died of Bright’s disease only seven months earlier. They had a quick and passionate courtship which

Edith met Woodrow Wilson during a chance encounter at the White House. His first wife, Ellen, had died of Bright’s disease only seven months earlier. They had a quick and passionate courtship which  answer to what the government should do if the president became unable to perform his duties. Wilson wasn’t dead, so there didn’t seem to be a reason for the vice president to step into his role. Without the 25th amendment, Congress and the Cabinet had no real power to act (and the extent of Wilson’s condition was kept top secret). To Edith, protective of her husband and his presidency, the answer was clear.

answer to what the government should do if the president became unable to perform his duties. Wilson wasn’t dead, so there didn’t seem to be a reason for the vice president to step into his role. Without the 25th amendment, Congress and the Cabinet had no real power to act (and the extent of Wilson’s condition was kept top secret). To Edith, protective of her husband and his presidency, the answer was clear.

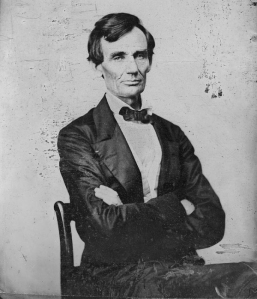

Lincoln wasn’t exactly smitten with Mary Todd. After they got engaged, Lincoln had second thoughts and he tried to get out of their engagement. Several of Lincoln’s friends recollected his misgivings about Mary, which Michael Burlingame documented in his book

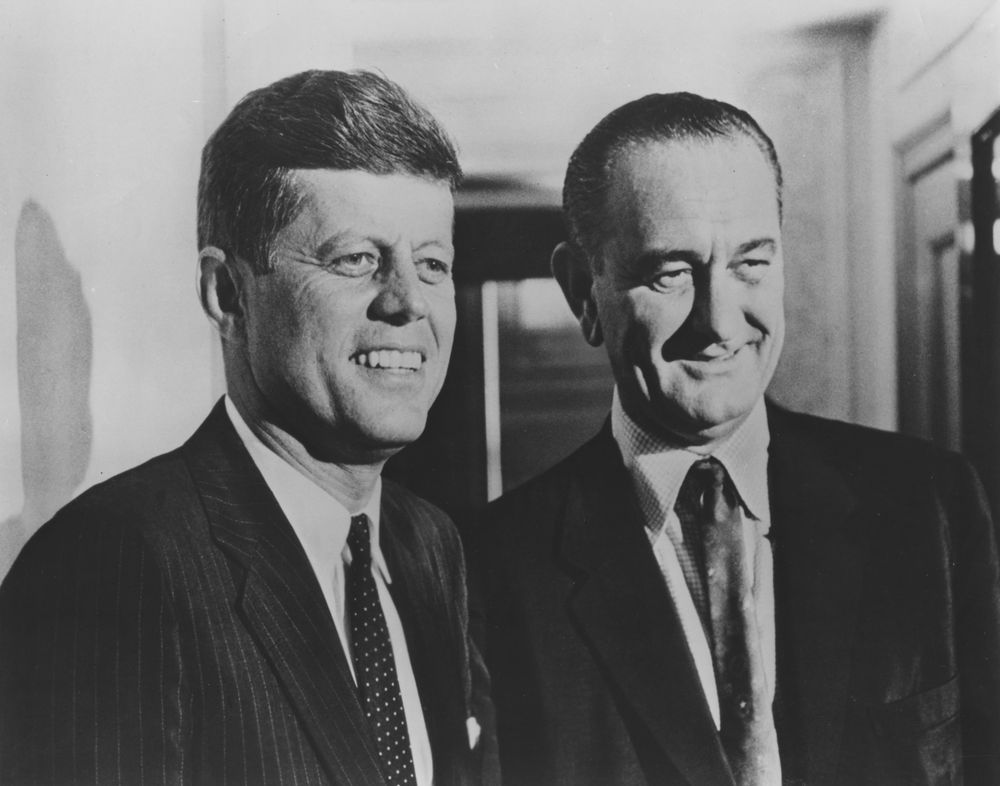

Lincoln wasn’t exactly smitten with Mary Todd. After they got engaged, Lincoln had second thoughts and he tried to get out of their engagement. Several of Lincoln’s friends recollected his misgivings about Mary, which Michael Burlingame documented in his book  General Ulysses S. Grant at his first appearance in Washington, D.C. as the top general in the Union army. That reception, a journalist noted, was the first time Abraham Lincoln wasn’t the center of attention in the East Room. Grant was elected president in the first election after Lincoln’s assassination. He might have been assassinated with Lincoln on April 14, 1865, if Mary Todd Lincoln hadn’t thrown a tantrum a few weeks earlier in front of Grant’s wife Julia Dent Grant. Even though the morning newspaper reported that the Lincolns and the Grants would attend a showing of

General Ulysses S. Grant at his first appearance in Washington, D.C. as the top general in the Union army. That reception, a journalist noted, was the first time Abraham Lincoln wasn’t the center of attention in the East Room. Grant was elected president in the first election after Lincoln’s assassination. He might have been assassinated with Lincoln on April 14, 1865, if Mary Todd Lincoln hadn’t thrown a tantrum a few weeks earlier in front of Grant’s wife Julia Dent Grant. Even though the morning newspaper reported that the Lincolns and the Grants would attend a showing of

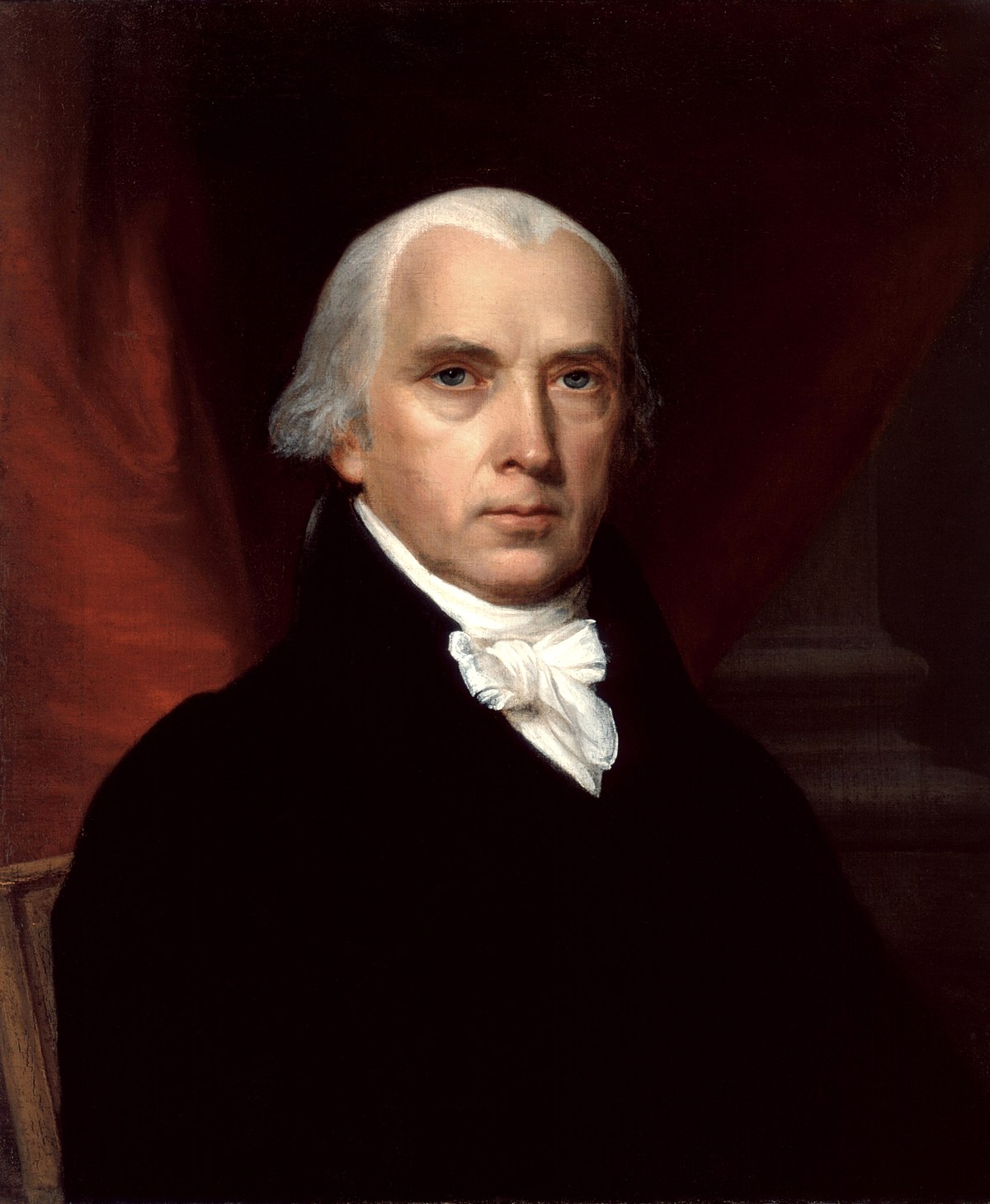

In David McCullough biography’s of Madison-foe John Adams, the nation’s fourth president is described as “a tiny, sickly-looking man who weighed little more than a hundred pounds and dressed always in black.” When Dolley Madison caught his eye and he asked for an audience with her (bonus trivia: mutual friend Aaron Burr set them up), she wrote her sister that “the great, little Madison” wanted to meet her. Great because of Madison’s political reputation; little because at 5’7, Dolley Madison was several inches taller than her future husband.

In David McCullough biography’s of Madison-foe John Adams, the nation’s fourth president is described as “a tiny, sickly-looking man who weighed little more than a hundred pounds and dressed always in black.” When Dolley Madison caught his eye and he asked for an audience with her (bonus trivia: mutual friend Aaron Burr set them up), she wrote her sister that “the great, little Madison” wanted to meet her. Great because of Madison’s political reputation; little because at 5’7, Dolley Madison was several inches taller than her future husband. the James Madison biography The Three Lives of James Madison by Noah Feldman, Feldman writes that Dolley was instrumental in forming Madison’s ability to converse with diplomats and their wives. “Under Dolley’s tutelage,” Feldman writes, “Madison developed what would become a lifelong habit of telling witty stories after dinner, the ideal venue for his particular brand of dry wit.”

the James Madison biography The Three Lives of James Madison by Noah Feldman, Feldman writes that Dolley was instrumental in forming Madison’s ability to converse with diplomats and their wives. “Under Dolley’s tutelage,” Feldman writes, “Madison developed what would become a lifelong habit of telling witty stories after dinner, the ideal venue for his particular brand of dry wit.” wanted to wait for his return. According to an account by Paul Jennings, a man born into slavery at Madison’s estate of Montpelier and then working at the White House, the table had been set for dinner when a rider came charing to the mansion with the message that they must evacuate immediately. Dolley wrote her sister that she insisted on waiting until they could unscrew the portrait of George Washington from the wall.

wanted to wait for his return. According to an account by Paul Jennings, a man born into slavery at Madison’s estate of Montpelier and then working at the White House, the table had been set for dinner when a rider came charing to the mansion with the message that they must evacuate immediately. Dolley wrote her sister that she insisted on waiting until they could unscrew the portrait of George Washington from the wall.