By Kaleena Fraga

If William Howard Taft’s hold on the collective American memory is that he got stuck in a White House bathtub (likely false), his wife Nellie’s grip is weaker still. Yet Nellie played a crucial role in propelling her husband to the White House, and her subsequent stroke during his term in office irrevocably changed his presidency for the worse.

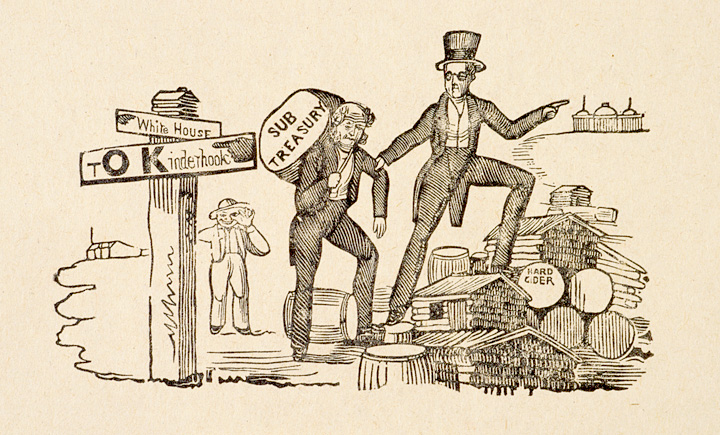

Née Helen Louise Herron, Nellie grew up immersed in American politics. Her father was a college friend of future president Benjamin Harrison, and shared an office with another future president, Rutherford B. Hayes. Hayes and Nellie’s father were especially close. When she was sixteen, Nellie was invited to accompany her parents to the Hayes White House for the president and his wife’s silver anniversary. Later in life, Nellie told journalists that, “Nothing in my life reaches the climax of human bliss, which I felt as a girl of sixteen, when I was entertained at the White House.”

Indeed, she told President Hayes that the visit had convinced her that she would marry “a man who will be president.” Hayes is reported to have responded, “I hope you may, and be sure you marry an Ohio man.” Hayes, Harrison, and the Herrons were all proud Ohioans (as was Nellie’s future husband).

Nellie herself was bright–she had a gift for languages, and studied French, German, Latin and Greek. She wrote in her diary that, “A book has more fascination for me than anything else.” Nellie wanted to continue her education–her brothers went to Yale and Harvard–but her father told her he could not afford to send her to college. Anyway, she was expected to find herself a husband, instead.

Nellie herself was bright–she had a gift for languages, and studied French, German, Latin and Greek. She wrote in her diary that, “A book has more fascination for me than anything else.” Nellie wanted to continue her education–her brothers went to Yale and Harvard–but her father told her he could not afford to send her to college. Anyway, she was expected to find herself a husband, instead.

But this sort of lifestyle didn’t suit Nellie at all. Out of school, unable to take as many music lessons as she wanted because her father didn’t think they were worth the money, Nellie found herself “blue as indigo.” She wrote in her journal that, “I am sick and tired of my life. I am only nineteen. I feel as I were fifty.” The solution, she thought, was to find a job. “I read a good deal to be sure…but I should have some occupation that would require active work moving around–and I don’t know where to find it…I do so want to be independent.”

One has to wonder what Nellie could have accomplished if her father had coughed up the money for her to pursue her own education–although in the 1880s, neither Harvard nor Yale admitted female students.

In the end, Nellie enrolled in less expensive classes at the University of Cincinnati, where she studied Chemistry and German.

Although it horrified her mother, Nellie eventually decided to take a job teaching at a private school for boys. Nellie’s mother wrote her a letter detailing her alarm at this decision: “Do you realize you will have to give up society, as you now enjoy it…it is quite the thing for a young girl in your position to teach in a boys school–and where there are no other ladies?” Nellie’s friends too questioned her “queer taste.” To this, Nellie wrote in her journal:

“Of course a woman is happier who marries, if she marries exactly right, but how many do? Otherwise I do think that she is much happier single, and doing some congenial work.”

At this point in her life, Nellie began to spend more time with William Howard Taft, a young lawyer whom she had had known as a girl and who had “[struck her] with awe.” Taft, for his part, started carrying books when he was around Nellie to gain her favor.

The first time he asked her to marry him, Nellie turned him down. According to Doris Kearns Goodwin, Nellie feared that marriage would “destroy her hard-won chance to accomplish something worthy in her own right.” Taft persisted. Perhaps he sensed that Nellie had ambitions beyond that of a wife and mother. Writing to try and convince her to change her mind, Taft said, “Oh how I will work and strive to be better and do better, how I will labor for our joint advancement if only you will let me.”

Nellie agreed and they were married in 1886.

When Taft became president in 1909, Nellie’s greatest dream had been realized. She had encouraged her husband to turn down President Roosevelt’s offers of a seat on the Supreme Court to keep his options open for the presidency (Roosevelt asked three times). Her great ambition of returning to the White House had become a reality. Although her husband admitted he felt “like a fish out of water” (indeed, Taft would later state that he hardly remembered his term in office–his true ambition, which he attained after his presidency, was to be the Supreme Court Justice), Nellie was right at home.

The New York Times noted that few had been so “well equipped” to be First Lady. Nellie had been a governor general’s wife during Taft’s tenure in the Philippines. She was social; she understood the ceremonies of the office; and she spoke Spanish, French and German, so she could hold conversations with diplomats from around the world. The new First Lady received accolades for her conversational skills, and her ability to converse on a variety of topics. She was quite a contrast to her predecessor, Edith Roosevelt, who believed, “a woman’s name should appear in print but twice–when she is married and when she is buried.”

As Taft began to take on the demands of the office, Nellie took on responsibilities of her own. She became an honorary chair of the Women’s Welfare Department of the National Civic Federation to advocate for workers in government and industry. Nellie refused the commonly accepted logic that college wasn’t for women, and publicly said so. Her own daughter eventually attended Bryn Mawr. When asked about women’s suffrage, Nellie stated:

“A woman’s voice is the voice of wisdom and I can see nothing unwomanly in her casting the ballot.”

Although some muttered that Nellie should focus more on “the simple duties of First Lady,” Nellie was equally eager to expand this role. Upsetting many New Yorkers, Nellie stated that she wanted to make Washington D.C. a social hub for Americans. Nellie set out to beautify the city. From her time abroad, Nellie had fallen in love with Japanese cherry trees and brought one hundred to Washington. When the mayor of Tokyo heard of this project, he sent 2,000 more.

Although some muttered that Nellie should focus more on “the simple duties of First Lady,” Nellie was equally eager to expand this role. Upsetting many New Yorkers, Nellie stated that she wanted to make Washington D.C. a social hub for Americans. Nellie set out to beautify the city. From her time abroad, Nellie had fallen in love with Japanese cherry trees and brought one hundred to Washington. When the mayor of Tokyo heard of this project, he sent 2,000 more.

“In the ten weeks of her husband’s Administration,” wrote the New York Times, “Mrs. Taft has done more for society than any former mistress of the White House has undertaken in many months.”

It was only a few weeks into Taft’s term that tragedy struck. Nellie, only 48, suffered a debilitating stroke. The right side of her face was paralyzed. Although the public was kept in the dark, Nellie had lost the ability to speak or express her thoughts in any way. She went to the family’s summer home in Massachusetts to recover. Taft needed his wife–needed her social drive and partnership. Weeks into his presidency, he had lost her.

Although Nellie recovered much of her facilities, she wasn’t able to play the part she so  dreamed of in Taft’s administration. It certainly wanted for her influence. Without her, Taft was not able to play the dynamic social role he needed to fill the shoes of his bombastic predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt.

dreamed of in Taft’s administration. It certainly wanted for her influence. Without her, Taft was not able to play the dynamic social role he needed to fill the shoes of his bombastic predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt.

Still, despite a second stroke in 1911, Nellie and Taft were able to celebrate their silver anniversary at the White House–the same event that Nellie had attended as a girl. One can only wonder what someone like Nellie could have accomplished if she’d had access to education; and if she’d lived in a world where women could pursue a career without judgement. Perhaps we’d be writing about her presidency, instead.

Special thanks to our girl Doris Kearns Goodwin & her wonderful Taft/Roosevelt biography: Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt & The Golden Age of Journalism.

book she’d purchased for her niece, which she’d discovered portrayed women as unequal to men. The note was a warning to read the book with a grain of salt. Abigail wrote: “I will never consent to have our sex considered in an inferior point of light.”

book she’d purchased for her niece, which she’d discovered portrayed women as unequal to men. The note was a warning to read the book with a grain of salt. Abigail wrote: “I will never consent to have our sex considered in an inferior point of light.” Abigail Adams was the first First Lady to live in the White House. She and John Adams moved to Washington D.C. from Philadelphia once the mansion was finished. As she wrote a friend, the executive mansion was huge and sparse. “It is habitable by fires in every part, thirteen of which we are obliged to keep daily, or sleep in wet and damp places.” Abigail used today’s East Room to dry the family’s laundry.

Abigail Adams was the first First Lady to live in the White House. She and John Adams moved to Washington D.C. from Philadelphia once the mansion was finished. As she wrote a friend, the executive mansion was huge and sparse. “It is habitable by fires in every part, thirteen of which we are obliged to keep daily, or sleep in wet and damp places.” Abigail used today’s East Room to dry the family’s laundry.

Barbara Bush met her husband at sixteen and married him four years later, after his brush with death during WWII. Before marriage Mrs. Bush had enrolled in Smith College–she was a voracious reader as a girl–and helped out in the war effort by

Barbara Bush met her husband at sixteen and married him four years later, after his brush with death during WWII. Before marriage Mrs. Bush had enrolled in Smith College–she was a voracious reader as a girl–and helped out in the war effort by  own political views, she was more outspoken before and after H.W.’s term in office. During his vice presidential run she

own political views, she was more outspoken before and after H.W.’s term in office. During his vice presidential run she

Nellie herself was bright–she had a gift for languages, and studied French, German, Latin and Greek. She wrote in her diary that, “A book has more fascination for me than anything else.” Nellie wanted to continue her education–her brothers went to Yale and Harvard–but her father told her he could not afford to send her to college. Anyway, she was expected to find herself a husband, instead.

Nellie herself was bright–she had a gift for languages, and studied French, German, Latin and Greek. She wrote in her diary that, “A book has more fascination for me than anything else.” Nellie wanted to continue her education–her brothers went to Yale and Harvard–but her father told her he could not afford to send her to college. Anyway, she was expected to find herself a husband, instead. Although some muttered that Nellie should focus more on “the simple duties of First Lady,” Nellie was equally eager to expand this role. Upsetting many New Yorkers, Nellie stated that she wanted to make Washington D.C. a social hub for Americans. Nellie set out to beautify the city. From her time abroad, Nellie had fallen in love with Japanese cherry trees and brought one hundred to Washington. When the mayor of Tokyo heard of this project, he sent 2,000 more.

Although some muttered that Nellie should focus more on “the simple duties of First Lady,” Nellie was equally eager to expand this role. Upsetting many New Yorkers, Nellie stated that she wanted to make Washington D.C. a social hub for Americans. Nellie set out to beautify the city. From her time abroad, Nellie had fallen in love with Japanese cherry trees and brought one hundred to Washington. When the mayor of Tokyo heard of this project, he sent 2,000 more. dreamed of in Taft’s administration. It certainly wanted for her influence. Without her, Taft was not able to play the dynamic social role he needed to fill the shoes of his bombastic predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt.

dreamed of in Taft’s administration. It certainly wanted for her influence. Without her, Taft was not able to play the dynamic social role he needed to fill the shoes of his bombastic predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt.

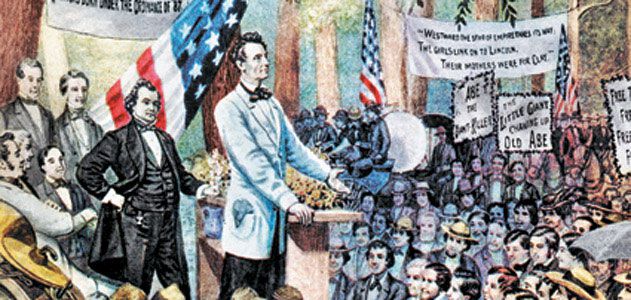

Racial violence perpetrated both sides of the conflict. That year, the Democratic Party ran a racist, anti-war campaign, warning that emancipation meant black people would move North in droves and force whites out of their homes. “The Constitution as it is, the Union as it was, and the negroes where they are,” was their campaign slogan. Democrats gained 34 seats in the House of Representatives, won gubernatorial races in New York and New Jersey, and won control of several state legislatures. In 1863, Horatio Seymour, the Democratic governor of New York, said, “I assure you I am your friend,” to anti-draft rioters who had lynched black doormen and burned down the Colored Orphan Asylum in New York City.

Racial violence perpetrated both sides of the conflict. That year, the Democratic Party ran a racist, anti-war campaign, warning that emancipation meant black people would move North in droves and force whites out of their homes. “The Constitution as it is, the Union as it was, and the negroes where they are,” was their campaign slogan. Democrats gained 34 seats in the House of Representatives, won gubernatorial races in New York and New Jersey, and won control of several state legislatures. In 1863, Horatio Seymour, the Democratic governor of New York, said, “I assure you I am your friend,” to anti-draft rioters who had lynched black doormen and burned down the Colored Orphan Asylum in New York City.  letter to Lincoln, “I have given the subject of arming the negro my hearty support. This, with the emancipation of the negro, is the heavyest blow yet given to the Confederacy … by arming the negro we have added a powerful ally. They will make good soldiers and taking them from the enemy weakens him in the same proportion they strengthen us. I am therefore most decidedly in favor of pushing this policy to the enlistment of a force sufficient to hold all the South falling into our hands and to aid in capturing more.”

letter to Lincoln, “I have given the subject of arming the negro my hearty support. This, with the emancipation of the negro, is the heavyest blow yet given to the Confederacy … by arming the negro we have added a powerful ally. They will make good soldiers and taking them from the enemy weakens him in the same proportion they strengthen us. I am therefore most decidedly in favor of pushing this policy to the enlistment of a force sufficient to hold all the South falling into our hands and to aid in capturing more.” Lincoln’s second inauguration happened on March 4, 1865, when Union victory was imminent. He closed his Second Inaugural Address by extending an olive branch to the defeated Confederates and looking ahead to Reconstruction: “With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and lasting peace among ourselves, and with all nations.”

Lincoln’s second inauguration happened on March 4, 1865, when Union victory was imminent. He closed his Second Inaugural Address by extending an olive branch to the defeated Confederates and looking ahead to Reconstruction: “With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and lasting peace among ourselves, and with all nations.”

4. Reagan-Bush ran a slogan in 1980 that will sound familiar to many Americans today: “Let’s Make America Great Again.”

4. Reagan-Bush ran a slogan in 1980 that will sound familiar to many Americans today: “Let’s Make America Great Again.” enthusiastic. The New York Times called the run up to the endorsement “one of Washington’s longest-running and least suspenseful political dramas,” after Reagan insisted on waiting for the end of the Republican primary to announce his pick. Despite his nickname as the “Great Communicator” and Bush’s eight years of service as VP, Reagan flubbed Bush’s name during the endorsement, pronouncing it George Bosh.

enthusiastic. The New York Times called the run up to the endorsement “one of Washington’s longest-running and least suspenseful political dramas,” after Reagan insisted on waiting for the end of the Republican primary to announce his pick. Despite his nickname as the “Great Communicator” and Bush’s eight years of service as VP, Reagan flubbed Bush’s name during the endorsement, pronouncing it George Bosh.

Still, he did face speculation of diminishing mental capacity during his presidency. In the aftermath of a poor performance in Reagan’s first debate with Democratic challenger Walter Mondale, a New York Times

Still, he did face speculation of diminishing mental capacity during his presidency. In the aftermath of a poor performance in Reagan’s first debate with Democratic challenger Walter Mondale, a New York Times