PART I

By Duane Soubirous

Heroes of American history are posthumously revered as gods by the Americans who follow them. Look at the ceiling of the U.S. Capitol’s rotunda and see Constantino Brumidi’s “Apotheosis of Washington,” depicting slaveowner George Washington’s ascent into heaven accompanied by the goddess of liberty. Walk into the Parthenon-inspired Lincoln Memorial and read Royal Cortissoz’s epitaph,

IN THIS TEMPLE

AS IN THE HEARTS OF THE PEOPLE

FOR WHOM HE SAVED THE UNION

THE MEMORY OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN

IS ENSHRINED FOREVER

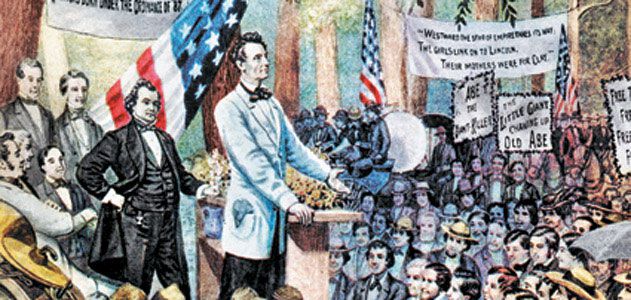

Etched in the walls of the Lincoln Memorial are the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural Address, both written within the last 18 months of Lincoln’s life. His earlier speeches go unmemorialized, like this passage from 1858 endorsing white supremacy:

“I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races – that I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people.”

W.E.B. DuBois quoted this passage in an editorial written in September 1922, four months after the Lincoln Memorial’s dedication. He believed that Lincoln should be honored as the imperfect human being he was, instead of a legend sculpted in marble:

“No sooner does a great man die than we begin to whitewash him. We seek to forget all that was small and mean and unpleasant and remember the fine and brave and good … and at last there begins to appear, not the real man, but the tradition of the man—remote, immense, perfect, cold and dead!”

Recognizing Abraham Lincoln’s flaws and contradictions doesn’t diminish his legacy, DuBois wrote, but rather enhances the worth and meaning of his upward struggle. “The world is full of people born hating and despising their fellows. To these I love to say: See this man. He was one of you and yet he became Abraham Lincoln.”

This three-part series will chronicle Lincoln’s upward struggle, from denouncing black suffrage to Illinois voters in 1858 to supporting black suffrage in his final speech in 1865, from unsuccessfully opposing the expansion of slavery as a one-term congressman to becoming the president who eradicated it.

Abraham Lincoln grew up on the frontier surrounded by what Frederick Douglass called “negrophobia.” It was common for frontiersmen living in free states to abhor slavery and emancipation alike: both were perceived as threats to the unalienable rights of white men. Lincoln didn’t address slavery in his campaigns for the Illinois State Assembly and U.S. Congress in the 1830s and 1840s, but Congressman Lincoln did support two proposals restricting slavery, neither of which succeeded.

In 1849, Lincoln proposed a gradual emancipation of slaves in the District of Columbia, but his plan wasn’t even brought to a vote. In 1862, after Lincoln signed into law the immediate emancipation of slaves in the capital, Lincoln said, “Little did I dream in 1849, when I proposed to abolish slavery at this capital, and could scarcely get a hearing for the proposition, that it would be so soon accomplished.”

Congressman Lincoln also supported the Wilmot Proviso, named for Pennsylvania Congressman David Wilmot. Wilmot wanted to keep slavery out of all territories gained from the Mexican-American War, giving white men to carte blanche to build a better life out West. The Wilmot Proviso passed in the House but failed in the Senate. Leading the opposition in the Senate was Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas, whom Lincoln challenged in 1858.

“If we could first know where we are, and whither we are tending, we could better judge what to do, and how to do it,” begins Lincoln’s “House Divided” speech, delivered upon securing the Illinois Republican Party’s nomination for Senate. Standing on the sidelines of the political arena in the 1850s, Lincoln observed each branch of government working conjunctively to expand slavery, and worried the United States was tending toward nationalizing slavery.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, shepherded through Congress by Senator Douglas, repealed a 34-year-old ban on slavery in the Kansas and Nebraska territories. Douglas insisted he didn’t care whether slavery be voted down or up, “but to leave the people thereof perfectly free to form and regulate their domestic institutions in their own way.” Lincoln attacked this principle of popular sovereignty, defining it this way: “That if any one man, choose to enslave another, no third man shall be allowed to object.”

In President James Buchanan’s inaugural address of 1856, he called on Americans to abide by an upcoming Supreme Court decision, “whatever this may be.” Two days later the Supreme Court issued its Dred Scott decision, ruling that Congress cannot ban slavery in the territories and the Constitution affirms the right to own slaves. This decision alarmed Lincoln. If the Constitution forbids states from denying rights affirmed in the Constitution, and the Supreme Court says the right to own slaves is affirmed in the Constitution, Lincoln reasoned that the Supreme Court would soon rule that states’ bans on slavery were unconstitutional. “We shall lie down pleasantly dreaming that the people of Missouri are on the verge of making their State free; and we shall awake to the reality instead, that the Supreme Court has made Illinois a slave state.”

Lincoln and Douglas debated seven times throughout the state. While Lincoln largely appealed to the audiences’ morals in denouncing slavery, Douglas resorted to race baiting. Responding to Lincoln’s assertion that the Declaration of Independence applied to both whites and blacks, Douglas asked how could Jefferson mean to include black people in the words “all men are created equal” when he himself held slaves? Furthermore, if slavery is wrong because the Founding Fathers meant for whites and blacks to be equal, what’s to stop freed slaves from voting, serving on juries, and marrying whites?

Lincoln spent the first three debates trying to dodge Douglas’ assertions that Lincoln believed in full equality for black people. At the fourth debate in Charleston, an especially racist part of the state, Lincoln definitively refuted Douglas: “There is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality.”

In 1858, Illinois’ senators were chosen by the state legislature: the people would vote for state representatives, and whichever party won a majority picked their nominee for Senate. Republicans won the popular vote, but Democrats won a majority of the seats, and Stephen Douglas was reelected as senator. However, Lincoln’s performance in the debates rose him to prominence throughout the North, and when the two ran for president in 1860, Lincoln would emerge the winner.

. Democrats voted together, against impeachment, and they were joined by five Republicans on the obstruction-of-justice charge.

. Democrats voted together, against impeachment, and they were joined by five Republicans on the obstruction-of-justice charge.

Four years before the 19

Four years before the 19 Mondale, who won the Democratic nomination. Formerly a member of the House of Representatives, Ferraro was the first female vice presidential candidate for a major party. Not surprisingly, the media focused on the novelty of a female on a major ticket and critiqued her on inexperience. Reporters called into question her marriage, family finances, and even tried to invent a connection to the Italian mob based on her family’s heritage. The campaign never recovered, and Reagan/Bush went on to win decisively in November.

Mondale, who won the Democratic nomination. Formerly a member of the House of Representatives, Ferraro was the first female vice presidential candidate for a major party. Not surprisingly, the media focused on the novelty of a female on a major ticket and critiqued her on inexperience. Reporters called into question her marriage, family finances, and even tried to invent a connection to the Italian mob based on her family’s heritage. The campaign never recovered, and Reagan/Bush went on to win decisively in November.

via scooter. The French barely blinked. In the 1990s, when Bill Clinton faced accusations of adultery while in office, the affair consumed the country. For Americans, the private lives of politicians and public officials are often important indications of their character.

via scooter. The French barely blinked. In the 1990s, when Bill Clinton faced accusations of adultery while in office, the affair consumed the country. For Americans, the private lives of politicians and public officials are often important indications of their character.

Cleveland claimed that the paternity was uncertain; his supporters dismissed the allegations as “boys being boys” although in 1884, Cleveland was 47 years old. Republicans reveled in this, and would gather to chant “

Cleveland claimed that the paternity was uncertain; his supporters dismissed the allegations as “boys being boys” although in 1884, Cleveland was 47 years old. Republicans reveled in this, and would gather to chant “

Jackson in 1836. This feat would not be repeated until 152 years later, when George H.W. Bush became president after serving as Ronald Reagan’s VP for eight years.

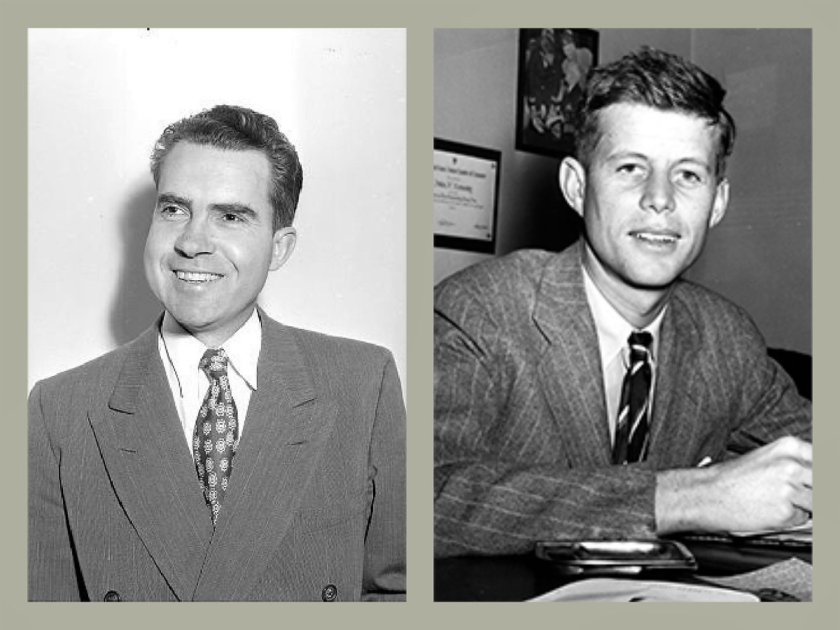

Jackson in 1836. This feat would not be repeated until 152 years later, when George H.W. Bush became president after serving as Ronald Reagan’s VP for eight years. death of the incumbent–eight vice presidents became president this way, including Calvin Coolidge, Teddy Roosevelt, and LBJ, who once eerily remarked before Kennedy’s inauguration that he’d accepted the number two spot because, statistically, there was a one in four chance Kennedy could die in office.

death of the incumbent–eight vice presidents became president this way, including Calvin Coolidge, Teddy Roosevelt, and LBJ, who once eerily remarked before Kennedy’s inauguration that he’d accepted the number two spot because, statistically, there was a one in four chance Kennedy could die in office.