By Kaleena Fraga

Since its founding, and despite a famous warning from George Washington, the United States of America has almost always been a two party system. In Washington’s day, it was the Federalists and the Democratic Republicans. Today, through much evolution, we have the Republican and Democratic Party, and more distance between them than ever before.

Aside from the 1850s, which saw the fall of the Whig party, the rise of the Know-Nothing party, and from this conflict the birth of the Republican party, the United States has usually had two major candidates to choose from. But today there is growing discontent toward the two major parties and the so called “establishment” class of politicians. Many Americans are itching for something different. Indeed, this longing is one of the reasons for Donald Trump’s election. But how feasible is an American third party, and when in history has the country attempted it?

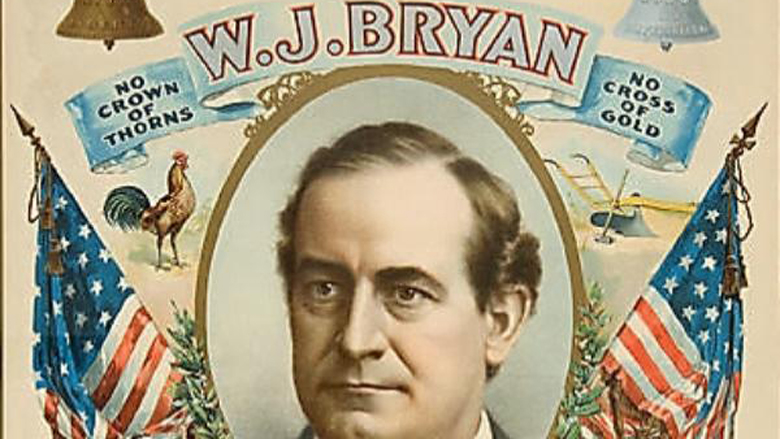

Third parties have always been around. In the 1890s the Progressive Party pulled the political conversation to the left and William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic candidate  in 1898, 1900 & 1908, flirted with many of their proposals. In the election of 1912 Teddy Roosevelt upended the process by storming out of the Republican National Convention and creating the Progressive Party, or the Bull Moose Party. After failing to convince the delegates to nominate him, instead of the incumbent president William Howard Taft, Roosevelt thought he could still win the election as a third party candidate. All he did, however, was divide Republican votes and give the election to the Democratic nominee, Woodrow Wilson. A Republican operative at the time remarked that the drama between Taft and Roosevelt was like complaining over which corpse got more flowers—the party division would surely give the election to the Democrats. Fun fact: although Roosevelt called the party the Progressive Party, he’d been widely quoted as saying that he felt “as fit as a bull moose” following an assassination attempt. Bull Moose stuck.

in 1898, 1900 & 1908, flirted with many of their proposals. In the election of 1912 Teddy Roosevelt upended the process by storming out of the Republican National Convention and creating the Progressive Party, or the Bull Moose Party. After failing to convince the delegates to nominate him, instead of the incumbent president William Howard Taft, Roosevelt thought he could still win the election as a third party candidate. All he did, however, was divide Republican votes and give the election to the Democratic nominee, Woodrow Wilson. A Republican operative at the time remarked that the drama between Taft and Roosevelt was like complaining over which corpse got more flowers—the party division would surely give the election to the Democrats. Fun fact: although Roosevelt called the party the Progressive Party, he’d been widely quoted as saying that he felt “as fit as a bull moose” following an assassination attempt. Bull Moose stuck.

Indeed, most candidates haven’t gone as far as Roosevelt in creating their own party when seeking to change the political conversation. Although George Wallace ran as the American Independent Party candidate in 1968, he sought the Democratic nomination in 1964, 1972, and 1976. Barry Goldwater, although holding more extreme views than many Republicans, still sought (and won) the Republican nomination in 1968 over the more moderate republican candidate Norman Rockefeller. In 1976 when Ronald Reagan ran against the incumbent president Gerald Ford, he did so as a Republican, not as a third party candidate. Likewise, Ted Kennedy ran against Jimmy Carter in 1980 as a Democrat. During this race one Democratic operative remarked that the party needed some unity medicine—to turn around three times and say out loud President Ronald Reagan. And, indeed, in both the Reagan-Ford and Carter-Kennedy case the party dynamics divided the party and contributed in the elections of Jimmy Carter in 1976 and Ronald Reagan in 1980.

The election of 1992 saw the impact a third party could have—Ross Perot ran against Bill Clinton and George H.W. Bush as the Reform Party candidate. Despite dropping in and out of the race, Perot participated in the debates and won nearly twenty percent of the vote, making him the most successful third party candidate since Roosevelt and the Bull Moose party. Perot arguably drew away Republican votes, and Clinton won an unexpected victory against an incumbent president. Despite the success, the Reform party is no longer a heavyweight in American politics—although it continues to nominate candidates.

The election of 1992 saw the impact a third party could have—Ross Perot ran against Bill Clinton and George H.W. Bush as the Reform Party candidate. Despite dropping in and out of the race, Perot participated in the debates and won nearly twenty percent of the vote, making him the most successful third party candidate since Roosevelt and the Bull Moose party. Perot arguably drew away Republican votes, and Clinton won an unexpected victory against an incumbent president. Despite the success, the Reform party is no longer a heavyweight in American politics—although it continues to nominate candidates.

The election of 2016 is a good indication of the power a third party can have, as well as a possible indication of future electoral trends. Voters, frustrated with both parties, turned out for 3rd party candidates like Jill Stein and Gary Johnson. Although both Johnson and Stein won only small portions of the overall vote, they gained thousands of votes in crucial districts. In Michigan for example, Johnson and Stein won approximately 222,000 votes. Trump won the state by only 15,000 (https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/2016-election-day/third-party-candidates-having-outsize-impact-election-n680921)

Even voting for Trump himself, a decidedly non traditional Republican candidate, is an indication of discontent among the American electorate, and a desire among voters for someone outside the traditional two party structure.

As the country speculates about the next election (it seems incredible, but the campaign will likely start next year, in 2018) the normal question to ask is who among the Democrats will run. For 2020 however, it seems that Democrats might not be alone in presenting a viable nominee to run against Trump. First of all, there’s a good chance that Trump, like Carter and Ford, will face a challenger from within his own party. Trump, at least today, is a historically unpopular president and it’s likely that the battle for the soul of the Republican Party will spill out into the 2020 primaries.

The Republicans aren’t the only ones infighting. Scars from the 2016 primary between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders continue to agitate Democratic voters and operatives. If Democrats cannot present a candidate who is sufficiently liberal, it’s certainly possible that someone from the Bernie Sanders wing of thinking could run as well. Given that Sanders is not technically a Democrat, this person could, in theory, run as an independent to the left of the Democratic candidate.

But what would be really interesting is if a candidate emerged to the center of both parties. Over the last half century, the country has seen the divide between the left and right deepen. The repeal of the Fairness Doctrine in the 1980s created an opening for right-wing talk shows and news networks like Fox News, which present a decidedly partisan view of the world. Meanwhile, the Democrats are also promoting liberal news agendas. Podcasts like Pod Save America are not timid in presenting and endorsing liberal ideas and interpretations of current events. Both parties are moving away from center; meanwhile many Americans feel left somewhere in the middle. There are purity tests on both sides and it’s become normal for someone to be challenged from the extreme wing of their own party.

It seems, then, like an ideal time for a centrist third party candidate. Discontent toward  the two party system is growing, the two parties are becoming more extreme in their ideology, and American voters are suffering from continuing partisan gridlock in Washington. Perhaps many voters imagined Donald Trump would be the kind of president who could break through the gridlock, without having a true allegiance to either party. But he’s proven himself to be a partisan with no interest in reaching out to voters outside his base. What the country needs in a third party candidate is someone more like Eisenhower—a person, not necessarily a politician, who is well-liked and well respected by Americans of both stripes, who is apolitical but accomplished. The world saw a similar phenomenon in the election of Emmanuel Macron in France—Macron created his own party and took down candidates to both his left and right.

the two party system is growing, the two parties are becoming more extreme in their ideology, and American voters are suffering from continuing partisan gridlock in Washington. Perhaps many voters imagined Donald Trump would be the kind of president who could break through the gridlock, without having a true allegiance to either party. But he’s proven himself to be a partisan with no interest in reaching out to voters outside his base. What the country needs in a third party candidate is someone more like Eisenhower—a person, not necessarily a politician, who is well-liked and well respected by Americans of both stripes, who is apolitical but accomplished. The world saw a similar phenomenon in the election of Emmanuel Macron in France—Macron created his own party and took down candidates to both his left and right.

But can it happen here? Only time will tell.

(Featured image credit: http://axiomamnesia.com/2012/02/28/americans-political-party-as-gonna-fix-american-politics/)

in 1898, 1900 & 1908, flirted with many of their proposals. In the election of 19

in 1898, 1900 & 1908, flirted with many of their proposals. In the election of 19 The election of 1992 saw the impact a third party could have—Ross Perot ran against Bill Clinton and George H.W. Bush as the Reform Party candidate. Despite dropping in and out of the race, Perot participated in the debates and won nearly twenty percent of the vote, making him the most successful third party candidate since Roosevelt and the Bull Moose party. Perot arguably drew away Republican votes, and Clinton won an unexpected victory against an incumbent president. Despite the success, the Reform party is no longer a heavyweight in American politics—although it continues to nominate candidates.

The election of 1992 saw the impact a third party could have—Ross Perot ran against Bill Clinton and George H.W. Bush as the Reform Party candidate. Despite dropping in and out of the race, Perot participated in the debates and won nearly twenty percent of the vote, making him the most successful third party candidate since Roosevelt and the Bull Moose party. Perot arguably drew away Republican votes, and Clinton won an unexpected victory against an incumbent president. Despite the success, the Reform party is no longer a heavyweight in American politics—although it continues to nominate candidates.  the two party system is growing, the two parties are becoming more extreme in their ideology, and American voters are suffering from continuing partisan gridlock in Washington. Perhaps many voters imagined Donald Trump would be the kind of president who could break through the gridlock, without having a true allegiance to either party. But he’s proven himself to be a partisan with no interest in reaching out to voters outside his base. What the country needs in a third party candidate is someone more like Eisenhower—a person, not necessarily a politician, who is well-liked and well respected by Americans of both stripes, who is apolitical but accomplished. The world saw a similar phenomenon in the election of Emmanuel Macron in France—Macron created his own party and took down candidates to both his left and right.

the two party system is growing, the two parties are becoming more extreme in their ideology, and American voters are suffering from continuing partisan gridlock in Washington. Perhaps many voters imagined Donald Trump would be the kind of president who could break through the gridlock, without having a true allegiance to either party. But he’s proven himself to be a partisan with no interest in reaching out to voters outside his base. What the country needs in a third party candidate is someone more like Eisenhower—a person, not necessarily a politician, who is well-liked and well respected by Americans of both stripes, who is apolitical but accomplished. The world saw a similar phenomenon in the election of Emmanuel Macron in France—Macron created his own party and took down candidates to both his left and right.

are eager to add the -gate moniker to anything that appears to suggest impropriety. This knee jerk reaction to make Nixon the boogeyman of American political commentary is lazy, and unfair to his administration’s accomplishments in office.

are eager to add the -gate moniker to anything that appears to suggest impropriety. This knee jerk reaction to make Nixon the boogeyman of American political commentary is lazy, and unfair to his administration’s accomplishments in office.

st to John Adams and served as his vice president. But today, a loser must go from being one of the most admired (or reviled) people in the country to last week’s headline.

st to John Adams and served as his vice president. But today, a loser must go from being one of the most admired (or reviled) people in the country to last week’s headline.